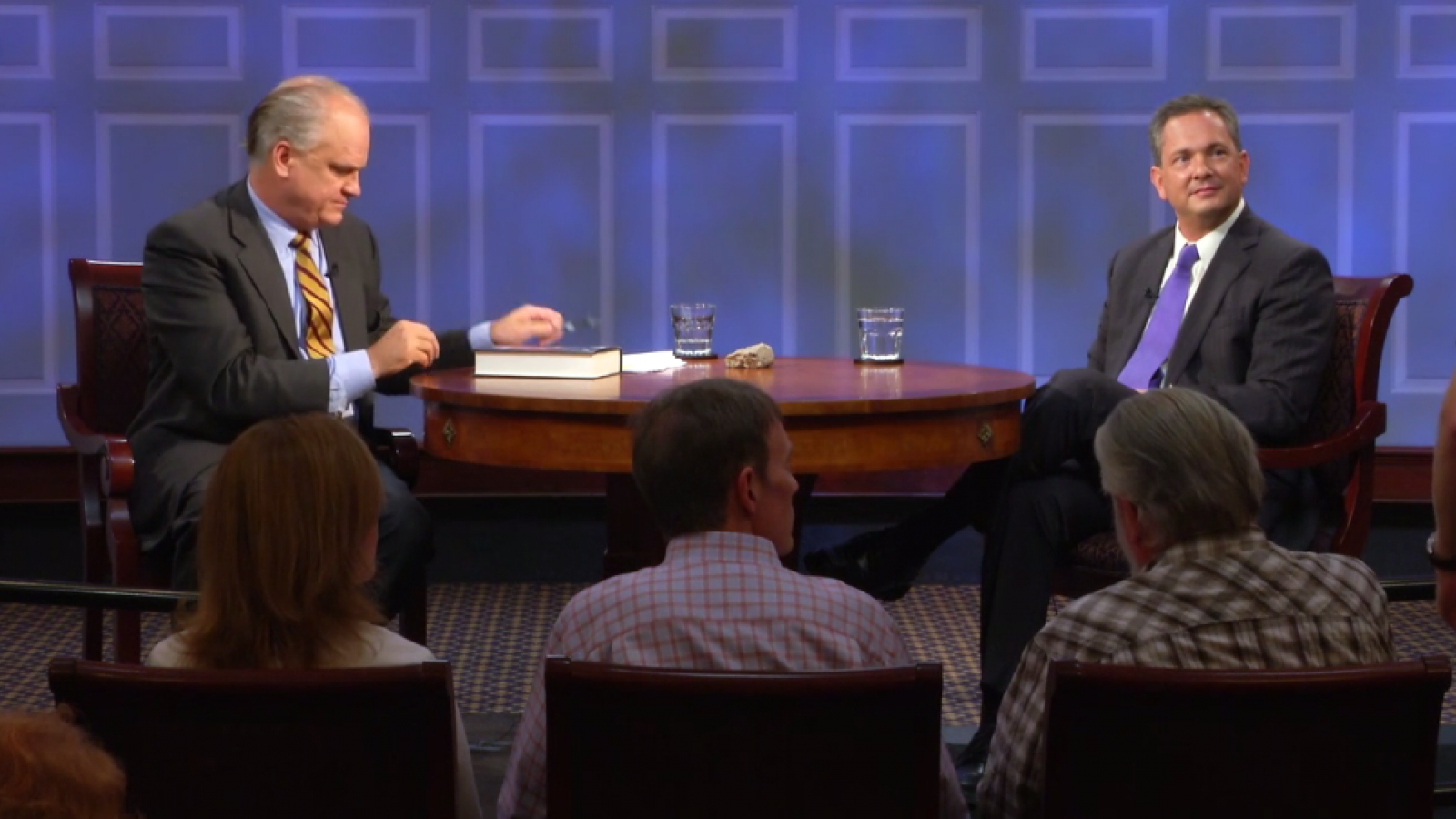

About this episode

November 22, 2017

Jeffrey Engel

Hosted by Douglas Blackmon

When President George H.W. Bush was inaugurated on January 20, 1989, he began a presidency defined by a reordering of the world. The Cold War came to an end, leaving Russia with an uncertain future. A rising new China cracked down on pro-democracy protestors at Tiananmen Square. Detractors deemed the first President Bush too cautious to deal with such staggering change. Admirers saw him as prudent and respectful of crucial international norms. That was four presidencies ago. Today our relationship with Russia is deeply strained. We face the threat of a nuclear North Korea. And at home, we are bitterly divided. So did George H.W. Bush save the world or allow it to fall apart? Joining us in this week’s episode is JEFFREY ENGEL, director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University and the author of the recently released book When the World Seemed New: George H.W. Bush and the End of the Cold War—an intimate portrait of a president and a singular moment in the history of democracy.

Transcript

00:40 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. When President George H.W. Bush was inaugurated on January 20, 1989, he began a presidency defined by what would become a breathtaking and at the time still unimaginable re-ordering of the world. The Cold War came to an end, but Soviet leadership reforms that promised to transform their country were far from a certain success. The Berlin Wall fell, presenting an opportunity to accomplish the impossible: peaceful re-unification of Germany.

The rising new China cracked down on pro-democracy protestors at Tiananmen Square, raising doubts about its new position in world leadership. Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, triggering the First Persian Gulf War, but also tipping in motion dominos that continued falling for a decade, and set the stage for President Bush’s son to embark on a disastrous second invasion of Iraq. George Herbert Walker Bush was a man detractors deemed too cautious, and too detached to organize a new world order at such a moment of staggering change. Former Texas Governor Ann Richards called him an elite, born “with a silver foot in his mouth.” But admirers saw him as prudent and respectful of crucial international norms. They said what looked like caution was thoughtfulness, and quiet leadership, that his commitment to “First Do No Harm” in foreign relations allowed the U.S. to emerge from the Cold War as the world’s last great superpower. Rather than a silver foot, they said Bush wielded a steady hand through the final phase of a Cold War that had terrorized the world through the Atomic Age and set a path for democracy to spread peacefully and inevitably across the globe. That was four presidents ago; things looked so promising. Yet our relationship with now “Russia” is deeply strained after its annexation of Crimea in 2014, its assaults on the Ukraine, and interference in our 2016 national election. We face a mounting threat of nuclear war with North Korea, and terrorist groups like Al-Qaeda and ISIS continue to destabilize the Middle East, in part as a result of anarchy that, in some respects, was a byproduct of the end of the Cold War. And, at home, without the clear, absolute dangers of that era, our own politics also trend toward chaos. So, what really happened in that short presidency of George H.W. Bush? Did he save the world, or allow it to fall apart? Joining us in this episode is Jeffrey Engel, director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. He has a new book, When the World Seemed New: George H.W. Bush and the End of the Cold War. It is an intimate portrait of a president and a singular moment in the history of democracy. Thank you for being here.

Jeffrey Engel: Good to be here.

03:33 Blackmon: You open the book with this very interesting anecdote about what would seem to be not necessarily all that important a thing—but a ride in a limousine with George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev on the way to the White House for a summit with President Reagan, and—really not necessarily a president with—a summit with Vice President Bush, but with Reagan.

FACTOID: Gorbachev was general secretary of the Communist Party 1985-91

And you describe this—the conversation that happens, it's—on the way to that. And also, in the midst of it, when Gorbachev orders that the limousine stop, and he hops out and rushes over to the crowd and the—and interacts with them, and Bush is sort of flummoxed by the whole thing. But what is it—what's the significance of that sequence, just—and tell us the story if I've left something out.

Engel: Well, it's really an amazing story of an intimate moment between two men who are ultimately going to change the fate of the world in many ways. Gorbachev—this is in 1987. Gorbachev is literally the most famous man in the world, the most popular man in the world. He's in Washington, D.C. in order to meet with President Reagan. And, of course, Vice President Bush hopes to someday be president. He is about to announce his own campaign. So, he wants desperately to be seen next to the most popular person in the world. And as they ride in this limousine down to the White House, they begin to discuss how there's going to be an election coming up, how—"Mr. Gorbachev, you need to understand the way American elections work. I might have to say things," Bush says, "that would sound a little bit off-putting, but it's for domestic ears." And Gorbachev says nothing, says not a word. Suddenly, as you mentioned, he orders the limousine to stop. He rushes out to the crowd, and Bush is left sitting there, wondering where his guest went. Bush, of course, joins him, and the whole point of this is that Gorbachev and Bush tumble back into the limousine, and Gorbachev says, "We can be unpredictable, as well. We can do things, we know politics, as well. We have our own politics." And at that moment, I think, the two men really did not know each other, really did not trust each other, but had a sense, I think, that both of them are going to be integral to whatever happened next.

05:37 Blackmon: To me was—it was, just in a very simple sort of way, this reminder of the degree to which—that in—particularly in that period of time, the inability of Americans and American leadership to consider the possibility that Soviet leadership—were not necessarily just evil people trying to rule the world, but were, in their own way, engaged in a relationship with the Russian people and the people of the world. Yeah, that—and it just seemed like in one tiny way, you just captured that.

Engel: Yeah, well, this—this is really at the very heart of the problem that Bush faces when he takes office, that Gorbachev has promised a new world. He has promised to reunite East and Western Europe. He's promised an age of peace. He's promised disarmament. He's promised to change the Soviet system, inside and out. He's promised a revolution. The problem from Bush's perspective is: if Gorbachev is successful, that means the Soviet Union is going to be stronger. If Gorbachev fails, that means chaos might come or Gorbachev might be removed and the Soviet Union might become stronger. And there's a real problem for Bush to wonder: do I believe this person? Is he just doing this as some kind of huge, Machiavellian trick on the world, which seemed a very likely possibility. And frankly, the people that Bush brought with him into the White House were universally convinced that President Reagan had been too trusting, that he had essentially tried too hard to get disarmament, tried too hard to extend a hand to the Soviets, beyond what evidence would suggest prudent.

07:03 Blackmon: Yeah, no, it's just a fascinating sort of thing, and I think at—that that—that tension threads through a bunch of the other things that we'll talk about, but—so, I mentioned in the intro, Bush's Basel notion of "Do No Harm, First Do No Harm," a Hippocratic diplomacy, as you’ve called it. But what exactly—what's that? What is Hippocratic diplomacy that he embraced?

Engel: Well, to understand Hippocratic diplomacy, you have to go back and really understand who Bush is. Bush is a fundamentally establishment figure in American politics. He is, to my mind, the most—single most experienced person ever to be elected President of the United States. Not only was he vice president, as you mentioned, he was Director of the CIA, he was a businessman. He also was a U.N. ambassador, he was de facto ambassador to China and so and so forth. Head of the RNC, [Blackmon: In Congress long before, right.] Yeah, he's as intimately involved in the American system as possible and comes from a family that's also intertwined in the American system. So, from Bush's perspective, the world works. The world works when people follow the American pattern, when people believe in free markets, when people believe in free speech, when people believe in democratic institutions, and the—even when you have chaos in the world, even when you have people outside the world system like the Soviets, in time, they will come to appreciate that the world is moving in our direction.

FACTOID: Prescott Bush was a United States senator from Connecticut 1952-63

So, from Bush's perspective, whenever he faces a crisis, he knows that the worst thing that he can do is really to row, if you will, down the stream of history, to push the envelope, to use another metaphor—that what he really wants to do is let things play themselves out, because as long as things don't go bad, they're going to go our way. And that's really fundamental to understanding his perspective, and also the perspective of optimism that was rampant throughout this entire period from the American perspective, with one important caveat, which is we must always remember that the Soviet collapse, without an ensuing great power war, is really an—historical anomaly. The expectation, whenever an empire collapses, is that there will be a war later, and the world had never actually yet faced a situation where we have an empire collapse with 20,000 nuclear weapons in the mix.

09:02 Blackmon: So, then, Bush becomes president in January of 1989, and then by November of 1989, the—you know, the world is completely spinning apart. In fact, in early November 1989, I'm running around Berlin—here's my chunk that I know is for real, because I cracked it off the Wall myself, (laughter) and—with an East German guard standing on the Wall.

Engel: Did you check it for asbestos?

Blackmon: I did not. [Engel: Okay, okay.] So, I may have just signed your death warrant. (laughter) But the—but so, the world is, you know, is completely turning over, but then this question of Germany becomes this absolutely central event in how is this reordering of the world going to go? I don’t think we remember as much about it now, in the passage of time, but that—okay, the Wall is coming down.

FACTOID: Berlin Wall fell Nov. 9-10, 1989; Germany reunified Oct. 3, 1990

Clearly, the old way is over. But is East Germany really going to be allowed to reunite with West Germany? What's going to happen to the rest of the Warsaw Pact? Gorbachev thinks the Soviet Union—and the other—the Russian leadership thinks the Soviet Union, for sure, is going to survive. And even a lot of people in the White House assume that some version of the Warsaw Pact will remain as some kind of a coalition. But just—well, give us that scene, in a sense, of the—it's November '89, and what—at the White House, President Bush and his other key advisors, what are they sorting through?

Engel: Well, I think you even have to go beyond November and go back into October and September, because as late as those days, as late as October '89, no one thought German unification was an issue. It wasn't even something we need to discuss, because that's so far in the future that—Helmut Kohl, for example, the leader of Germany said, at that point, in October of 1989, "I don't expect to see unification in my lifetime."

FACTOID: Kohl chancellor of West Germany 1982-90, of unified Germany to 1998 So, everything that subsequently happens takes everyone by surprise. Events move by the crowd. Events move out of control. And it's really fascinating to watch Bush—and now we have all the documents and all the records—to watch Bush in the White House watching this on TV, watching people scaling the Berlin Wall, on the one hand being unable to fathom that this is actually happening, this thing that we've talked about but never thought would happen is happening. And the second thought, recognizing we don't know what comes next. And constantly, Bush is asked by his press secretary, Marlin Fitzwater, time and time again, "Mr. President, you must give a statement to the press. You must give a statement to the press." And Bush demurs, demurs, finally says yes. They call the press in and it is a marvelous master class in how a president can speak for half an hour and say nothing, (laughter) because Bush tried dramatically not to say anything at all, because he knew something that the reporters didn't, which is that he was simultaneously getting telegrams and phone calls from other leaders around the world, whether it's Mikhail Gorbachev, whether it's Helmut Kohl, whether it's Margaret Thatcher of Britain, basically saying, "We're all scared. We don't know what's going to happen next." And Bush desperately didn't want to say anything that would either excite the crowd, perhaps in Berlin, to violence—or, more dangerously, because no one expected the Wall to fall and because the Wall was so symbolic and because the Wall was clearly falling because of something Gorbachev has done, this provides a lot of energy and evidence to Gorbachev's domestic enemies. Perhaps this is the sort of thing that will cause a coup, Bush worries, [that?]—

12:22 Blackmon: Or this—what we saw in Hungary, you know, the last time that there was an opening up, what seemed to be an opening. And so, how late into all of that is there still an active question or—of: is it possible that something could happen where the Soviet tanks actually rolled into East Germany and stopped this whole thing, which the United States would not have stopped, right?

Engel: No, there's not—there's actually no way we would have stopped it, because that would have led to—directly to nuclear war. You know, it is not a resolved issue, I think, until nine, ten months later, [Blackmon: Yeah.] after the Wall falls—by the way, it's not inevitable that we're going to get unification. It's not inevitable that the East Germans are going to be able to join the West Germans. And more specifically, from Bush's perspective—and this is really key to understanding everything that he cares about—it's not necessarily logical or inevitable that the new Germany, which had been the dividing point between East and West, would all stay with the West. It's entirely possible that Germany could become neutral. It's entirely possible that Germany could somehow be part of both the Warsaw Pact and NATO in some new, creative way. It's not at all clear how this new map is going to form. And, at the same time, it's not clear that Gorbachev is either going to allow these things to happen or, I think what's more likely is, the man who takes over for Gorbachev could've sent the tanks in. That's the real worry from the Americans' perspective.

13:37 Blackmon: And so, then there's the—so, there's this dialogue that's happening between the U.S. and Gorbachev. There's also all these other world leaders. There's a great quote you've got where there's a conversation between Margaret Thatcher and President Bush where she's expressing this concern that the Germans are going to—that if reunification proceeds, the Germans are going to get, through peace, what Hitler could not accomplish through war. And so, that's this other element of—that they're—and it's—this is even harder for us to remember now, that there's actually still some live fear and anxiety about the notion of a united, strong Germany at the center of Europe, actually a very accurate forecast of what was going to happen in the succeeding years. But so—but to what degree is that an element of the formula?

Engel: It's crucial, because memories of the Holocaust are still very fresh in 1989. Memories of World War II are still very fresh. Every single leader that Helmut Kohl, the leader of Germany, has to deal with, lived through World War II. Margaret Thatcher remembered being bombed. Mikhail Gorbachev thought he had lost his father for over a year and a half until his father suddenly returned, as a great surprise, from the battlefield. They understood what the Germans [inaudible]

14:55 Blackmon: And President Bush is a World War II veteran, as well.

FACTOID: Bush flew 58 combat missions and earned distinguished flying cross

Engel: Right, right. He, of course, served in the Pacific, but he understood the same basic—this idea, and the basic narrative for all those people was that—whether true or not, this is what they believed—that the Germans had been solely responsible for World War I, but more importantly for World War II. So, they looked at history and said, you know, every time the Germans get together, something bad happens. And from the American perspective—and this is really key—the American perspective of: every time the Europeans get together without us, something really bad happens. You know, from Bush's perspective, we went off and won World War I and then went home, and then we had to do it again. And that time, we stayed, and there hasn't been a European war since. So, when Bush is watching the jigsaw puzzle of Europe essentially break apart, his primary concern, above all else, above all else, is—above keep—and after he's established peace—is to ensure that there is still an American presence in Europe. And this is essentially at the heart of German unification—is not only whether or not Germany is going to allow—to come—be allowed to come together, but whether it's going to be allowed to come together in a formula that's still going to allow the Americans to stay in Europe. And this, I think, is really Bush's signature achievement. And when we talk about the Gulf War—we can talk about other events, but to be honest, he is, as much as anyone, the father of the new Germany and of the new Europe.

16:13 Blackmon: And so, let's bring this all into the—into this really clear discussion of the present, is there a contribution—whether this speaks to Bush or to those who followed him—that better diplomats, better leaders might have navigated this more successfully? Or even a second term of President Bush, would that have been very different?

Engel: You know, I think one could easily say that it could have been better, but I don't know that—necessarily we would have gotten a fundamentally different outcome.

FACTOID: Bill Clinton defeated Bush in 1992 election by nearly six million votes

I think that the truth of the matter is, the hard truth of the matter is the Soviet people were going to suffer dramatically in the transition to capitalism no matter how much aid was given, no matter how well things were done. And perhaps they would like more aid and perhaps the oligarchs could have been kept without so much control. But the truth of the matter is, first of all, no one had ever done this before. No one had ever taken a superpower from one economic system to another overnight, but—and second of all, there was going to be suffering. So, from the average voter's perspective—the average Russian voter, we should remember, didn't like Gorbachev by the end, because as far as they're—he was concerned, Gorbachev had come in and my breadlines got longer.

FACTOID: 2017 poll: 8% of Russians view Gorbachev positively, Stalin 46%

Gorbachev came in and actually tried to take away my vodka. I mean, he—you know, Gorbachev had problems politically, and was—

17:20 Blackmon: That is a bad thing, [Engel: It is. Well it's—] taking away your vodka, yes.

Engel: If you're Russian, yeah. And so—and actually, it actually causes a real economic problem for the Soviets, because much of their tax base had been from vodka sales. So, yeah, you're losing on both ends. So, from the Russian perspective, things were going to get bad. And the truth of the matter is, I think that people, when things get bad, want to have someone else to blame. And it's easy to blame the other guy for not doing enough, especially when the other guy—the United States in this case, and a period, if you're Russian, when you are suffering—is striding the world as a global hegemon. I mean, let's remember that when the United States goes to war with Iraq, and then subsequently when the United States leads a military effort against the Serbs, through NATO, both of those, the Iraqis and the Serbs, are long-time Russian allies.

FACTOID: Russia’s GDP in 1991 was $518 billion; U.S. GDP was $6.2 trillion

It would be as though—you know, it would be as thought, you know, we allowed the Russians at the end of the Cold War to bomb the Canadians, you know? We have a long history with these people. We have—we are their neighbors. We would not take too kindly to that. Now, I'm not trying to stress the Russian perspective as correct. I just think we need to understand the Russian perspective in order to understand better how to deal with how they understand their pasts and where we can go in the future. All the changes that we're talking about here are unprecedented, and we haven't spent a lot of time talking about the other half of the equation, from Bush's perspective, which is what's going on in China, which, of course, is going through a dramatic change, going through democratic protests, and unlike in Eastern Europe, it leads to violent revolts. But from Bush's perspective, these are basically the same problem—and let's find a same solution to them, and that solution is—goes back to first principles. We believe in democracy and we believe that history is moving in that direction, and we believe states become more integrated—as states become more integrated, they will become more prosperous, more free, and more democratic.

19:00 Blackmon: And you wrote an essay for the First Year Project that we did here at the Miller Center and talked a lot about in this program, where you were talking about the essential lessons for the first year of a presidency which—you know, talk about a first year of a presidency—George Bush, and—but some of your takeaways were take time to reassess policy, rethink convictions, reshape national security bureaucracy so that it reflects who the president is. Take time, take time, take time before implementing solutions. Give subordinates an opportunity to learn how to best work with each other. Let subordinates do things that would—one would suggest that would mean don't say the secretary of state's talks with—around the most important issue in geo—global geopolitics are useless and a waste of time. That's probably not the approach you would advise. Prudence, caution, judgement, experience, patience.

Engel: Well, and there's actually one other lesson from this story and the story of George H.W. Bush that is particularly applicable for our own times today, which I did not anticipate when I wrote this. I mean, none of us anticipate our times today [Blackmon: Yeah.] when we start projects ten years ago. And one of the things that really impressed me about Bush throughout this entire project was his willingness to suffer political harm publicly because he knew that what he was doing privately was for the public good. So, what that tells us is that a president needs to essentially be a little bit more Teflon, if you will. A little stronger in their own personal convictions and not so much concerned with the next headline if they really believe that they're going forward in the right direction.

20:27 Blackmon: Well, yeah, you're describing a kind of detachment, you know, kind of a mature detachment between leaders and the media consequences that—not detachment in a term—in the terms of indifference, but just a willingness to say some things are not going to resolve themselves tomorrow, and we won't know how this is going to work for some period of time. And we may be criticized for this, and we're going to have to accept that—yeah, that's a kind of discipline and maturity, really, that is unimaginable now. And I'm not just talking about President Trump. I mean, I think you could say that there has been a somewhat steady deterioration of that idea, including the second President Bush—I mean, probably is the—that's the other great irony to me, is that he approached the great challenge of his presidency with a similar kind of absolute belief that we've got the right ideas, and also that the people, even the people we're going to invade—that they may not know as much about democracy as we would like, but as soon as they get a little bitty taste of it, even with us standing there with guns, they are also going to embrace this. And it turns out that their definition of pursuit of happiness was different than the one that we were bringing, and it was much more complicated. I think that—is it fair to say that the second President Bush brought not nearly so sophisticated a comprehension of these things, flawed or not, as his father did.

Engel: I think there's—there is that, and there's also—I think the fundamental way to understand the two bushes is that they both believed in the same thing, but through different methods. They both believed, as you pointed out, that everybody wants freedom, innately, and they never really questioned these ideas. They both believed that everybody wants to be democratic. They both believed in free markets. The difference is the first President Bush was willing to let the stream of history take us all their at its own time, and the second President Bush was interested in paddling and was interested in catalyzing change and moving change faster, I think, than the first President Bush, who thought we'll get there eventually and we'll get there slowly and we'll get their without rapids, was willing to take his time in a way that his son—and, to be granted, because of 9/11, felt he didn't have the luxury of that time.

22:29 Blackmon: So, let's just imagine for a second that it's about—maybe the last thought here—let's imagine, though, that after first President Bush's humiliating defeat at the end of his presidency—and really, some respects, a kind of a very unfair—you know, terms of whether he really was a successful president or not. But to his shock and dismay, he loses. Let's imagine for a moment that he had then been kidnapped and put in a time capsule (laughter) or some sort of state of stasis. [Engel: Okay.] And—

Engel: Not where I thought where you were going with this, yeah.

Blackmon: And now, he's just been released. And so, it is the George Bush from 1991, and he's back with us. Now, we all know, I think, that the Republican Party of today would probably not recognize him as a Republican for the most part. But if—nonetheless, if he were on the stage and we—and he was sitting here with us now and we said, "Okay, truth serum, you know, don't—you just—let's inject the truth serum. But now tell us, if we—if there was some way we could put you in the White House right now and you were taking on the challenge of Putin, currently, and taking on the challenge of North Korea," what do you think that President Bush would say our first steps should be?

Engel: I—that's a great question. You know, I think that he would apply a domestic logic as well as an international one. One of the things that was really critical about Bush that I think is largely true of most presidents is that he recognized that he was essentially a trustee of the presidency and that he had to make sure that the presidency was—still had credibility. So, he would have, I think, been very concerned about the fact that we are no longer seeing the White House as a place of national unity, but also seeing the White House as a place of rationality and that facts matter, that evidence matter—President Bush would not have been recognized in today's Republican Party because he believed in climate change, things of that nature.

FACTOID: Over 280 members of Congress deny human-made climate change

By the same token, internationally, I think Bush would have essentially said, "We've got crises in North Korea. Don't make it worse. We have a crisis in Russia. Don't make it worse." Let's go back to North Korea for a second. Every day that we're not at war is a good day, and every day that we're not at war—because the history is moving in our direction, maybe slower than we'd like but it's still going there—we are more likely to get a peaceful outcome if we just don't screw it up. And I think that that's a real important lesson that requires a lot of strength and a lot of personal strength. I mean, just to go back—one more anecdote to—the fall of the Berlin Wall. I mean, imagine if President Bush, who was having private conversations with global leaders around the time of the Wall, had felt the need to publicly respond to reporters saying, "Why isn't Bush more—doing more?" He knew he was doing more. The fact that he knew he was doing more was enough. He didn't need to have everybody else know it, too.

25:13 Blackmon: Jeffrey Engel, thanks for being here.

Engel: Thanks for having me.

Blackmon: To our viewers, we invite you to share comments or ask questions about this or any other episode of American Forum. You can reach out to me via email or on Twitter @douglasblackmon, you—to learn more about the first Bush presidency, the second Bush presidency, or any other administration. Visit us at MillerCenter.org. You can also watch previous episodes of American Forum, or got to our Facebook page to watch a live taping of almost every episode. See you next week.