About this episode

March 26, 2017

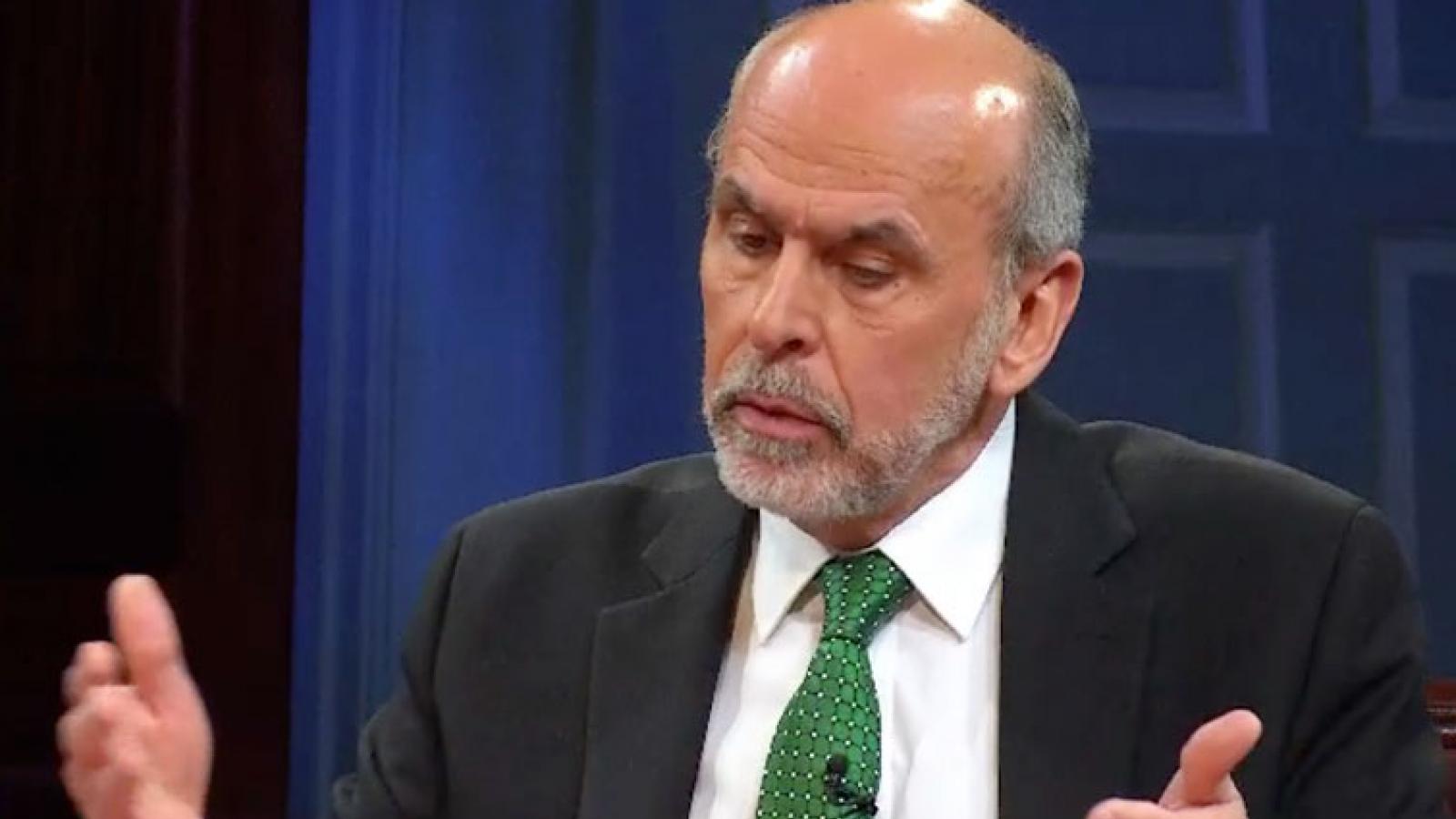

Gerald Seib

Gerald Seib, the Wall Street Journal's executive Washington editor and chief commentator, discusses President Trump's communications style, his relationship with the media, and the implications for the presidency and our democracy with host Doug Blackmon

Media and the Press

First Year 2017: Trump, Twitter, and the media

Transcript

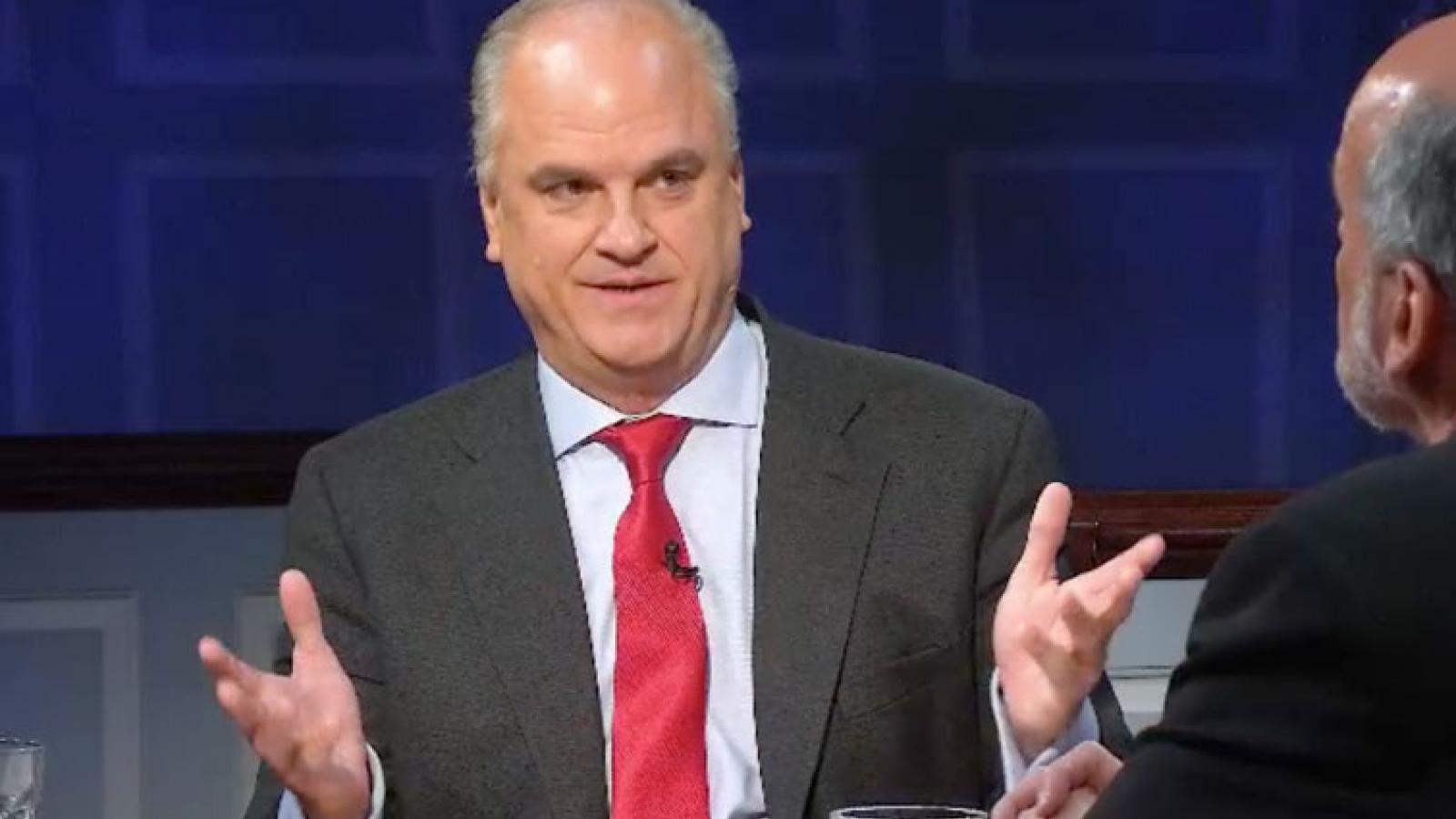

Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. It’s called the “bully pulpit.” Our gregarious twenty-sixth president, Teddy Roosevelt, coined the phrase as he pontificated about the evils of monopolies and other mega-issues of the early twentieth century. He knew that his position as president, his bully pulpit, gave him megaphone power. Every president since then has used that pulpit differently, from Silent Cal Coolidge, who nonetheless held more news conferences than any other president—a total of 521—to FDR’s fireside chats, to JFK’s televised news conferences. Every president has chosen how to shape his own particular bully pulpit. And now we have Donald Trump, who has set the traditional media on edge with his obsession with Twitter, sending about four tweets per day to his roughly twenty-six million followers. Meanwhile, he has largely refused to work with the media in any traditional sense, waiting four weeks after his inauguration to hold his first solo news conference, and banning certain media organizations from some White House briefings. Even more, he has repeatedly attacked the media, calling many of the most prominent news organizations “the enemy of the American people.” Is that just a matter of style, or is the new way our president communicates, as some might say, dangerous to democracy? And what about the press itself? Does any of this even matter, when a September Gallup poll showed that only 32 percent of Americans had confidence in the media, the lowest in Gallup polling history? As part of the Miller Center’s First Year Project, we have been exploring the risks and rewards of different ways our presidents have communicated with the American people. So our question today, is Donald Trump’s relationship with the media genuinely damaging, or is it just an innovative, new version of the bully pulpit? Joining us to discuss all this is a member of the traditional media, a legendary one. Jerry Seib has reported for the Wall Street Journal for almost forty years. He is now executive Washington editor, after spending twelve years as the newspaper’s Washington bureau chief. He writes a weekly column, “Capital Journal.” So he still gets ink on his fingers, but you are also likely to know him from his television appearances. He is the face of the Wall Street Journal in Washington on TV and across the internet. Jerry was also my colleague at the Journal for most of twenty years, and I can say, on the basis of thousands of interactions around the most important stories in American life, there has never been a better-informed, better-sourced, more ethical, more fair, more patriotic, or wiser journalist in our country. He is the walking, talking antithesis of fake news.

Gerald Seib: I’ll take that as a compliment.

Blackmon: It’s great to see you.

Seib: Thank you very much.

Blackmon: I just laid it on heavy.

Seib: I noticed that, yeah.

3:30 Blackmon: All true. You’ve been in the communication business for forty years. You’re at the very top of the game. How is it that Donald Trump seems to be so much better at it than you and everybody else in the business?

Seib: Well, look, I mean for starters, you have to say that Donald Trump is a master at communications. Whatever you think of him, whatever you think of the things he communicates, his ability to control the agenda is exquisite. He showed it for eighteen months during the campaign. He managed to create an aura in which CNN, for one example, was carrying almost all of his early rallies live, from start to finish.

FACTOID: CNN had 1.5 million daily viewers for prime time campaign coverage

There was a famous moment in which Donald Trump had attracted so much attention because of his style that CNN showed, during a long stretch one day during the campaign, an empty podium while they were waiting for Donald Trump to appear, which drove the other campaigns crazy, batty. They couldn’t believe that this was what was happening. But he had figured out how to take the oxygen out of the room for everybody else. Part of that was his rallies, and subsequently, it’s been his Twitter feed. I think what he does is he figures out how to control the agenda by creating bright, shiny objects that everybody turns toward, almost every day. I think that, in time, that will probably wear off, and people will stop paying so much attention to the bright, shiny objects, but for now, he’s good at what he does.

Blackmon: People have this idea that the Times is a liberal newspaper, and so it would be friendlier to a Democratic administration. The reality was that the New York Times, and to some degree the Washington Post, has been the daily organ of the White House for a century.

FACTOID: New York Times has three million plus readers, online subscriptions at washpost up 145%

In some respects, whatever the president said by some means yesterday has always been at the very center of the news the next day. Now Trump is doing it. He’s just skipping over the leak to the Times or to somebody else. But so, what is it that makes this different from that?

Seib: Well, it is a much more conscious effort to cut out the middleman, to cut out the mainstream media in particular. I think, though, that it kind of misses the point of what people who are in our business ought to be about, which is not just conveying what somebody says, although that’s important in a democracy, but it’s to put it in context, to analyze it, to explain it, to make it meaningful to people. That’s still the function of journalism. That’s the first function of journalism, and we just can’t walk past that, because I think, in the end, smart, objective journalism still wins out, even in this cluttered media environment.

FACTOID: Seib’s “Capital Journal” column is published in Tuesday Wall Street Journal editions

6:04 Blackmon: You wrote a column a few weeks back talking about the president’s style of doing this, and essentially making the observation that there’s a method to this madness, and it may not be madness at all. But you talked about that he’s by, by doing this, he positions himself for a negotiation, he’s controlling the agenda, and he’s creating rabbits for other people to have to run down. Uh, and certainly, the wiretapping tweets were a tremendously successful way of getting people off some of the problematic issues, like the Russia controversy.

Seib: Yeah, the subject before the wiretap tweets was Russian interference in the election, and potential Russian collusion with the Trump campaign. Suddenly, he, in one morning, a Saturday morning, remarkably enough, between 6:30 and 7:30 AM, makes the subject whether President Obama had wiretapped his phones in Trump Tower or not. Now, I think in that case, he probably went a little too far, because there’s really no evidence of that at all. And, whatever kind of surveillance there might have been, I don’t think anybody’s come up with any evidence that suggests President Obama wiretapped Donald Trump’s phones in Trump Tower. But it did have the effect, as you suggested, changing the subject to one that put the preceding administration on defensive rather than the current administration. That’s kind of what you see. You see it sort of over and over again during the campaign. It is, to a certain extent, what a president—you referred at the outset to the bully pulpit. The president has always had the power to do this, to basically find a way to declare what the subject is that’s of most import to the country at that moment. He just does it in a real time, and in a completely different way. Mostly effectively, but occasionally these things blow up. I think the wiretap example is one where it blew up.

7:52 Blackmon: I don’t think I’m overstating it—that when we all saw those tweet on that Sunday morning about the wiretapping, we also all knew that, well, it’s a 99.9 percent probability that this is untrue.

FACTOID: Trump ranks 44th biggest, with over 27 million Twitter followers Everybody knew that from the very beginning, and so, in a way, if everybody knows what you’re saying isn’t true, then in a way, it doesn’t matter that it’s untrue.

Seib: You know, I don’t think that—Trump followers don’t expect him to speak the literal truth every time out of the box. That’s something we learned during the campaign. There’s this great debate, should we take the president seriously but not literally? That’s the phrase—[Blackmon: Some people said that.] Yeah, they take him seriously, but not literally. I heard his people say that at a post-election conference. Corey Lewandowski, his former campaign manager, said to a group of journalists at a Harvard post-election conference I was at, “The problem with you journalists is you took everything he said literally.”

FACTOID: Lewandowski is now pundit on FOX and one America news network

You think, well, wow, how else are we supposed to take it? But the message was, don’t take it literally. He’s sending signals and laying down markers, but not telling the literal truth. This is a different phenomenon, because entire legions of journalists in our lifetimes have spent their time fact-checking presidents, doing kind of truth checks, and then literally trying to figure out whether what a president or another politician says is correct or not, in long, sort of detailed parsing of statements. Well, maybe we’re beyond that now, because I don’t think—I think people understand that he’s sending a signal, not delivering truth, necessarily.

9:25 Blackmon: If there’s kind of an understanding around it all, with the American people, then what is the downside of that?

Seib: Well, ok, so that’s a really important question. Let me—two parts to my answer to that. The first is that there is a danger here for the president, leaving aside any of the rest of us, that when he really does want people to take seriously and literally something he says, does he lose the ability to do that by creating all of these previous incidents in which it’s clear you shouldn’t take what he says literally? There will come a moment in a presidency when you want to be taken literally and seriously and at face value, and I think the danger is that that moment will arrive and he will have lost that ability. So that’s one issue. The second issue, though, is that I think the one thing that I learned, at least, during the campaign, was that Trump supporters think he’s speaking some larger truth. They’re not concerned about the smaller truths. They think he’s speaking some larger truth. We’re getting taken advantage of in the international economy by our trading partners. They’re fleecing us. We’re piling up debt that’s going to bankrupt our children. That’s not going to happen anymore. Nobody respects us anymore. We can’t stop ISIS, and we’re still spending hundreds of millions of dollars trying to fix Iraq after thirteen years. That’s not going to happen anymore. These are the bigger truths that I think his followers thought they heard. To them, that was the point, not the literal truth of any individual statement under any of those big topics. So that’s how they have decided to interpret Donald Trump, and the rest of us have to decide, how do we deal with that?

You know, he tweeted out one day that Barack Obama released from Guantanamo Bay 122 prisoners who had returned to the battlefield. Turns out 122 people who were released from Guantanamo Bay did return to the terrorist battlefield, the intelligence community thinks, but 113 of those, all but nine of them, were released by George W. Bush, not by Barack Obama. So you can’t let that sort of thing pass without pointing out, this is wrong. It’s not correct. It is factually incorrect to say what the president said in a tweet. That’s where our job as kind of parsers of truth still has to come into play, I think. Look, I think you’re touching on something that gets to the much broader backdrop of what we’re talking about here, which is the decline of confidence in American institutions, least of all the presidency; probably more the press, Congress, the political establishment, the financial establishment.

FACTOID: 2016 Gallup Poll showed 32% have trust in major American institutions

The fact is, people have gotten to a point of skepticism and perhaps cynicism about all those institutions. They don’t tend to believe what they’re told anyway. I think that’s an issue that we have to deal with as a profession, journalism, and we have to sort of cope in an environment in which people are, much more than when I started in this profession, inclined to not believe what they’re told, even when they’re being told it by institutions that they used to trust. And maybe this is a phase in American history, maybe it’s just the new reality, but that’s the backdrop against which all of this takes place.

12:26 Blackmon: Is it also possible that part of what’s happening is that President Trump, he does seem to get the American people, and at least an important part of the American people—he does seem to get what they want and how they want to hear it, in a way that is, to journalists, uncomfortably more effective, more persuasive, maybe more accurate. But is that also a version of just that the media, in some respects, is a little too big for its own britches? Things like, there was big news one night that the Trump entourage left Trump Tower to go to a restaurant and didn’t take the pool reporter along. There was a couple hours of cable news reporting about the offense of leaving behind the reporter, not telling the reporter where they were going, and how that violated convention. I was watching that, even as a former reporter, and I was thinking, that sounds really petty. Is it possible that that’s the case?

FACTOID: Pool reporters disseminate news to other participating news groups

Seib: Well, look, that sort of thing sounds petty, but I think one of the things about these conventions that we all operate under, they’re there for a reason. It turns out that it is important to the White House to have reporters who can verify where the president is at any given moment, because at some point, you don’t want Americans to think the president has disappeared. That’s not a healthy thing for a democracy in a twenty-four/seven news environment. There’s a reason—[Blackmon: Hiking the Appalachian Trail.] Just to cite one example. Yeah, exactly. I think we have to be modest enough in the media to admit that we missed some things in 2016. Donald Trump saw things that none of us did. He saw this underlying economic insecurity out in the country, and saw it as much broader than we thought it was. He saw that people believe that America is losing its edge, that it is being taken advantage of by foreign competitors in the economic sphere and in the security sphere. He saw that people aren’t comfortable. They think they’re losing control of their country. They don’t recognize the country that they live in anymore. It’s not the one I grew up in. He recognized all those things and validated those concerns for people, and they appreciated it. I have to admit that he saw the depth of those feelings more accurately than I think those of us in the mainstream media did, and that’s why he won. Let’s face it.

14:40 Blackmon: One of the mysteries to me about this time is that, in this whole failure of confidence in institutions—and it’s failure of confidence in the presidency, failure of confidence in Congress, in the media, but also even in our military in some respects—and President Trump has pushed the boundaries of a lot of these things. His comments about John McCain not necessarily being a war hero. You said a second ago, you were in the Middle East for three years ago. Well, it’s not just that; you were taken hostage in Iran. You were held, and fortunately survived, and were released. We were both friends with Danny Pearl, who was killed by Al-Qaeda. I got shot at in Yugoslavia before I got to the Wall Street Journal. None of that seems to account for anything anymore.

FACTOID: Pearl was killed in 2002 while reporting for Wall Street Journal in Pakistan

Seib: People want to know the truth, and they have to have somebody who they can believe is a purveyor of the truth, in good times and in bad, in easy situations and in hard ones. Look, if you go into a war zone as a journalist, maybe some people are doing it for the thrill, but mostly you’re going into it because, if American interests are engaged, American voters, American citizens, have a right to know how that’s playing out.

FACTOID: Committee to Protect Journalists: 1,232 reporters killed since 1992 That’s really what—people who embed with the U.S. military are doing it because these are their sons and daughters going to war. They deserve a fair and honest and objective accounting of how things are going. This is a very basic idea. I don’t think anybody ought to want to mess around with the idea that that’s a good function in a democracy, and it’s what Americans expect. Now, I think some don’t necessarily think they’re getting it all the time, and they don’t really understand or recognize that they want it or need it, but I think, in the long run, that’s what really happens. I think what you do as a journalist—and Marty Baron, who’s the editor of the Washington Post, has a great phrase. He says, “We don’t come into the office every day trying to go to war. We come in to go to work.” Just go to work. Be objective, be skeptical, but be fair and objective, and do your job, and have the faith that that’s what people are going to recognize they need in the long run. That’s really our mission, I think, right now. And forever, really. Not new. It’s the same.

16:47 Blackmon: And there’s always controversy around it as well, and the Wall Street Journal had some controversy on that very thing of late. Jerry Baker, editor-in-chief now, the top editorial person at the Journal, being asked about the dilemma of when the president says false things and how you should report on things that you clearly know are false. And Jerry Baker made the argument—I happen to agree with it, though many people were bothered by it. He made the argument that reporters shouldn’t call these false statements lies, unless there is evidence of an intent to deceive. It’s fine to call them false, but he can’t call them lies, because it implies something else. What’s going on with that struggle, as it relates to the Wall Street Journal?

Seib: Well, I’m a little—the lie thing was interesting. I was surprised that it became a controversy, because it’s not actually all that complicated. I think what Jerry was saying was simply, if I’m going to call somebody a liar, it means I know that he misled with conscious intent, and that was his goal, as opposed to he just didn’t know what he was talking about, or that he didn’t have his facts straight. It’s very hard to discern intent. So I think all Jerry was saying—in fact, this is what most journalists have done anyway, is simply say, “Donald Trump said this; the facts are that.” The tweet about the prisoners released from Guantanamo Bay, which simply was factually incorrect. He says 122 prisoners were released by President Obama, returned to the battlefield. It turns out 113 of them were released by George W. Bush. So what we did was what I think you do. We wrote a story that said he said this, but misstated a key fact in doing so, explained what he said, and then said, parse out the numbers. These are the facts. People can decide whether President Donald Trump didn’t know what he was talking about or whether he intentionally deceived. They’ll have to make that decision for their own, but I think people are smart enough to figure that out. Nobody has ever communicated this way. Nobody has ever stirred around facts quite the way Donald Trump does. Journalistically, we’ve all struggled, I think, to come up with how do you deal with that, because we’ve never been here before.

18:51 Blackmon: I want to try a theory out on you and hear your reaction to it. My theory of this moment is that we are still grappling—simplest way to say it—with 9/11. The Wall Street Journal had a unique experience around 9/11. Our headquarters in New York were destroyed in the attack, and our paper won a Pulitzer Prize, mostly by getting a paper out the next day and covering the event, having been victims of it. But my view is that 9/11 was such a traumatic event for this society, the great empire of this century, and it so rattled the American psyche, and then it was further rattled by what ultimately became the mistakes around the invasion of Iraq that cost so many lives, cost so much fortune. Layered on top of that, a sense among the American people that it doesn’t make sense for families to be handing off the presidency. It doesn’t make sense for the Bushes to hand it off. It doesn’t make sense for the Clintons to try to hand it off. But the whole trauma of this thing set in motion a series of events that were unimaginable before, and that’s how we got Barack Obama. It’s not because we made so much racial progress. It’s that we suddenly were open to something radically different. That triggered a bunch of other things, and that’s what gave us Donald Trump. But that in the end, it’s all about this giant trauma, a decade of trauma. Is it possible that, once we get through this presidency, whether that’s four or eight years, that some sort of normalcy will actually come back? That we’re not going off a cliff?

Seib: “Return to normalcy” is something I hear a lot. Can we be normal again? I think there’s a lot to that. Nine eleven is the only—in four decades of covering stories, it’s the only story I’ve ever covered where, the moment it happened, you knew. You could say—we talked about it instantly—things will never be the same. It’s the only story I’ve ever covered where that was immediately clear. Things will never be the same. That’s true. Why were they never the same? Because I think it made Americans feel vulnerable. I agree with the theory in the sense that it was a profound change for Americans to feel like they were personally vulnerable. Couple it with a feeling that Americans had lost control of their economic destiny—and I think there are two factors there. I think one was technology, which turns out to be great, except when it takes your job away. That’s not so very good. And globalization of the economy, which people were told in the 1990s was going to be an unmitigated plus. I talked to a woman last week who said, “I lost my job down in Wise, Virginia, not very far from here, because the factory where I was a seamstress closed down and moved to Honduras.” People thought, we’ve lost control of our economic destiny as well. Then there’s kind of a multiculturalism that some people—I’m one of them—celebrate, because I think America is powerful because it’s multicultural and it’s a melting pot and all that. It scares some people at the same time. So you pile all those uncertainties, one on top of the other, and you get a feeling that people have that they’ve lost control. They don’t like that, because we’re Americans, we’re supposed to be in control of the world. I think Donald Trump arrives and says, “I’m going to put us back in control. I’m going to put you back in control of your economic life, and I’m going to put America back in control of the world and the way it works,” and that was a comforting message.

Seib: Even Trump supporters don’t expect him to turn all these forces around. He may say that he’s going to do that. I don’t think that’s what they believe or expect. I think they just want him to get the trend lines moving in the right direction. If he saves some American jobs, as he has, to some extent already, that will make people think it’s possible that we can turn this around. If he basically makes NAFTA work better for people like the woman who lost her job at the textile factory, then the people think, well, it’s possible. I don’t think he has to turn everything around. I think he has to show that he can switch the trend lines on some of these key things. I think the danger is that some people maybe did take the promise literally, and when he says, “I’m going to bring all the coal jobs back to Virginia or Kentucky,” and that doesn’t happen, then what’s the level of disappointment? That’s probably the danger. If you’re sort of a fifty-year-old, fifty-five-year-old, blue-collar worker in the Midwest, and it turns out the factories don’t come back, what’s the level of disappointment? Where does that leave people? That’s, I think, the other danger that he faces right now.

23:24 Blackmon: All right, journalists don’t like to give advice to anybody. You like to just criticize people. But in this case, I think it’s relevant to ask you to give some advice.

A young, new reporter at the Wall Street Journal comes to see you a few months after he started in the bureau and says, “OK, old man, you’ve been here so long. Tell me how to succeed.” What’s your one piece of advice for that young reporter?

Seib: Be honest. Be honest, and ah have confidence that honesty wins out. Don’t worry about how you do it. Just worry about—the forms of journalism are changing and will continue to change. What will not change is the reason journalism exists, which is to be a purveyor of fair and objective information to people who need it and actually want it, even if they won’t admit to you at that moment that they really do want it. So have faith.

24:15 Blackmon: Last thing. What’s your one piece of advice for the American people?

Seib: I’m an optimist. This transcends journalism, and it doesn’t matter what I think all that much. People say, “Oh, the country is in terrible shape. It was better in the old days.” I lived through the 1970s. Things weren’t so great in the 1970s. I think America is stronger than it’s ever been. I think it’s more vibrant than it’s ever been. I think there’s more innovation going on in this country. There’s an economic transformation. But I would say, relax. This is a great country. It’s as great as it’s ever been, and it’s going to get greater, and I don’t have any doubt about that.

Blackmon: Sounds like good advice. Thanks for being here.

Seib: My pleasure.

Blackmon: We hope you will join us for future editions of American Forum, where our focus is always on the presidency and the issues facing our nation. In upcoming episodes, Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz on the president and the economy, conservative icon Bill Kristol, and historian and author John Farrell on his new, much talked about biography, arguing that Richard Nixon, while running for president in 1968, attempted to sabotage peace talks between the U.S. and Vietnam. You can watch those programs on your local PBS affiliate, or to join our ongoing conversation, look for us on the Miller Center Facebook page, visit our new, revamped website at millercenter.org, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. Jerry Seib is @geraldfseib. See you next week