About this episode

April 23, 2017

William Kristol

William Kristol has been called a “loser” and a “dummy” by the president of the United States. For his part, Kristol, a founder and editor-at-large of the Conservative magazine the Weekly Standard, has described Donald Trump as “a repulsive person, with dangerous prejudices, who’s unfit to be president.” So what does Kristol make of the Trump presidency so far? We ask him that question and more as part of our ongoing look at the future of American Conservatism.

Political Parties and Movements

A "never Trumper" on President Trump

Transcript

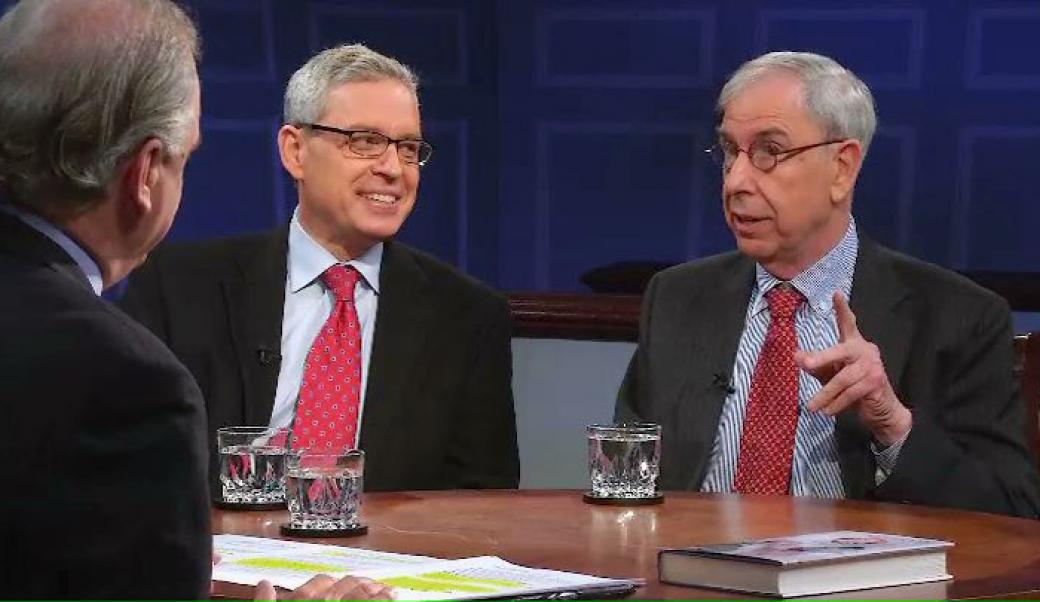

Doug Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. This week, conservative icon Bill Kristol.

MAIN TITLES/MX

0:46 Blackmon: Joining us this week is William Kristol, one of the most visible and vocal conservative critics of President Donald Trump. He is the editor at large of The Weekly Standard, a magazine he co-founded after the 1994 Republican sweep of the House and Senate, and a cornerstone publication of neo-conservative thinking. His father was Irving Kristol, sometimes called the “godfather of neoconservatism.” His mother is Gertrude Himmelfarb, an historian of intellectual ideas. He was a student of the famed Harvard professor of political philosophy, Harvey Mansfield, a college roommate of once perennial presidential candidate, Alan Keyes, and chief of staff to Vice President Dan Quayle during the George H. W. Bush administration. Despite that pedigree, President Trump has called Kristol a “loser” and a “dummy.” (laughter) After candidate Trump derided Senator John McCain’s war record last year, Kristol went on ABC News and said of the now president, “He’s dead to me.” (laughter) There’s no love lost there. An article in Politico last year said Kristol’s defiant resistance to the man who has become the leader of the Republican Party revealed Kristol to be, quote, "out of touch with the party he claims to be saving.” The Trump presidency is still in its infancy. But as part of our ongoing look at the Future of American Conservatism, today we ask what impact is this administration having on the conservative movement? Where should the Republican Party be looking now for leadership and a vision for its future? And finally, whether it’s possible for Donald Trump to unite the bitterly divided factions of the political movement our guest has influenced for four decades. Thank you for being here.

THE QUESTION: What is the GOP’s future under President Trump?

William Kristol: Good to be here, Doug.

2:24 Blackmon: On the day before the 2016 election, you wrote in The Weekly Standard that Donald J. Trump was, quote, “A repulsive person with dangerous prejudices who’s unfit to be president.” So, when Wisconsin was called for President Trump, now President Trump, on election night—and was clear that he would become president, where were you and what was your reaction? (laughter)

Kristol: I was actually on the set of ABC News in New York with George Stephanopoulos, and I was pretty much as surprised as everyone else. I—decide what I—well, despite what I said—I did think he shouldn’t be president and I made that point pretty clearly, but the voters chose not to agree with me. And I always thought he had a chance in the general election. In a change election, the candidate of the—of change, of the non-incumbent party always has more of a chance than you would think, just based on his credentials. People want change. I learned this when I was in the first Bush White House in ’92. First—George H.W. Bush was actually a pretty good president, you know? The country was not in terrible shape in ’92. We had won the Cold War without firing a shot. We’d come back from a mild recession, and people just said enough, twelve years of Reagan/Bush. Bill Clinton ran a clever campaign and beat us pretty handily. And I always use—I said this throughout the fall of 2016: if Hillary Clinton doesn’t have more of a positive message, I think she’s at risk of losing to Trump. I thought she would win, as most people did. I thought Trump had a one-in-four chance of winning, but then he pulled it out and surprised me and a lot of other people.

3:48 Blackmon: And though we haven’t yet had the kind of test—the most dramatic sorts of tests that we hope no president ever does face, but that—whatever that might be. A terrible [Kristol: Right.] terrorist attack or some act by a foreign enemy, but—and what’s your sense of how the institutions will interact with President Trump around something of much graver—

Kristol: No, that’s the right question. I mean, very much so, that—I mean, on the one hand, in crises, the president—the individual who’s president matters more. And all the bureaucracies that follow certain forms and the lawyers who insist on certain rules being followed and all the other institutions, they can check a president or do other things than what the president is doing. Those sort of fade away in a big foreign—in a big terror crisis or foreign policy crisis. And so, that will be—we haven’t experienced one of those, really. That will be an interesting question. And foreign policy, generally, I would say—foreign policy, generally, is an area where a mistake by a president can make more difference, probably, than in most areas of domestic policy. And that mistake is less likely to be checked. Now, even there, it’s interesting. He ended up appointing, you know, a very—one of the most respected generals in the United States military, Jim Mattis, the secretary of defense. A respected congressman as head of the CIA. A business executive, Rex Tillerson—a little unorthodox pick as secretary of state, but not a Trump loyalist and not a—someone who really goes along, necessarily, with everything Trump says. And actually, the one pick that was more Trumpian was his national security advisor, Mike Flynn, who I had my questions about, to say the least. But he was—had—blew himself up within a month, so to speak, and—not literally, but figuratively.

FACTOID: Flynn forced to resign after false claims about contact with Russia

You have to say that these days, you know? And (laughter) was replaced by H.R. McMaster, a very well-respected general who’s written a whole book about the mistakes of policy-making during Vietnam, who’s very much in favor of strong civilian control of foreign policy and so forth. So, even in foreign policy, there are the kind of institutional checks. I mean, Trump derided NATO when he campaigned, but now he occasionally says, of course, our allies should pay more, but he’s not blowing up NATO. He hasn’t blown up our trade agreements. It is interesting how much the sort of—the weight of history and institutions and the rest of the country kind of does constrain a president, even in foreign policy. But I agree, crises would be a different question.

6:08 Blackmon: You were last here, I think, in April of 2014. And there was conversation about the—how the Democrats and Republicans looked at the time and, you know, you gave some [Kristol: Right] prognostication, some sense of things. In those days, President Obama was—his approval rating was at 44%, and that was considered very bad in 2014. It would be a good number for President Trump right now, based on what we’ve seen most recently. But the GOP was just about to take control of the Senate. It already had the House. You sounded pretty optimistic about the Republican Party generally.

Kristol Library Interview: I’m reasonably optimistic about the Republican Party. They do need to be more…intelligent about reaching, not antagonizing some of these blogs. The good news, the best news for the Republicans is the quality of candidates in my opinion, running in 2014. There are a lot of younger, interesting, intelligent Republicans running…seem able to bridge the Tea Party Establishment divide. We’ll see if they all win the primaries, see if they win the general. Um, I find that most of these candidates…running for Senate at least…on the Republican side. And I would say the qua… not just the quantity but the quality of Republican senators could go up quite a lot in 2015. And I think that suggests that it’s also again not a party that’s simply fading away.

7:27 Blackmon: That was just three years ago. How does it look to you on those points today?

Kristol: It’s a good question, I actually look surprisingly similar if you just extend it to Trump. But let me come back to that in a second, because I think your point about the approval rating’s interesting. Another check on Trump is the public. For all that he’s got this magical ability to rally people and have huge rallies—and he does have, of course, a strong base of support—he’s drifted down from the 46 percent of the vote he got on Election Day to, what, about 36, 37 percent [Blackmon: That’s right] as we speak, which means about 20 to 25 percent of the people who voted for him don’t approve of the job he’s doing. On the Republicans, the irony is I don’t think I was wrong. The class of 2014—I’ve been watching it 30 years, and Republican all that time. The class of 2014’s one of the most impressive Republican classes that I’ve seen in the Senate. Younger, diverse in all kinds of ways. Lots of well-educated, intelligent people getting elected from a whole bunch of different states.

FACTOID: Nearly one in five members of Congress is racial or ethnic minority

Young House members, as well. And actually, there were good people elected in 2016, as well. So, I’m looking at Tom Cotton and—from Arkansas and Ben Sasse from Nebraska and Joni Ernst from Iowa and Dan Sullivan from Alaska and Cory Gardner from Colorado. I felt, well, that’s pretty good. That’s actually better than your typical, you know—well, you know, I won’t characterize the typical guys. But (laughs) it’s an upgrade. Lot of them young. The Republican conference in both the House and Senate is about seven years younger, if I’m not mistaken, than the Democratic conference, on average. So, they are the younger party in Congress. They were electing people from all over the nation. Some of them kind of moderate, liberal on immigration, some more hawkish. And, you know, diversity of views on different policies. And I did think the party had done a decent job of navigating the kind of post-Bush years, which were challenging in many ways. And I still think that’s—if you came down from Mars and looked at the Republicans in the House and the Senate and the governors, you wouldn’t say, oh, this is a disaster. You’d say, well, there are moderate Republican governors who are pretty popular in moderate states: Governor Hogan in Maryland or Kasich in Ohio or Baker in Massachusetts. There are conservative Republican governors who are doing pretty well for states that want more conservative governance. I can tell myself ‘til I’m blue in the face and tell you that, oh, the party’s in really good shape except for Trump. But that’s a very big “except for” (laughter) and one of the big questions, obviously, of the next three years, maybe seven years, is how much does the Republican Party become a Trumpite party? How much is Trump just a separate phenomenon that kind of does his thing and the party kind of moves ahead in somewhat different directions? How much does the party constrain Trump? Those are really huge questions that I think it’s hard to know the answer to right now.

9:51 Blackmon: You give this relatively positive assessment of the party, but you also, quite recently, have written in The Weekly Standard that there may yet be the need for a new party. What would a new Republican Party look like, and what are you talking about there?

Kristol: So, I guess that there are two things. I mean, one danger is, from my point of view—that you get a Trumpified Republican Party, which just becomes a kind of nationalist, populist party, anti-market or not pro-market, anti-trade, America first, sort of ethnic nationalism.

Blackmon: Which is sort of antithetical to what you would say [Kristol: Yes.] Republicanism, right?

Kristol: So, I don’t—I’m not for that. So, obviously, that’s not the kind of Republican Party I want. Now, it may turn out that some percentage of Republicans—obviously, some percentage of Republican primary voters are friendlier to that than I am. But people forget Pat Buchanan got Republican primary votes, Ron Paul, Rand Paul got Republican primary votes. The Democrats have their own, you know, fringes. Normally, those are 20, 15, 25 percent sometimes. And Trump is the first to win the nomination running on some version of that platform. A lot of it was just that he’s also a celebrity and an effective demagogue in general. And then win the presidency, obviously. So, part of this—the answer is how much does Trump shape the party? And then it turns out the party, despite having some attractive and impressive elements, was out of touch, obviously, to some degree, with its voters, has had to accommodate the new Republican president. I don’t really blame the elected officials much for that.

FACTOID: 26% of Americans identify as GOP, 30% Democats, 42% Independent

I’m in a different position than they are. They’re—they ran on the ballot with him, some of them. They—you know, he’s their president, they want to have a successful Republican Congress. They have majorities in both houses. They don’t want to simply fight him needlessly. They’ll give him sort of the benefit of the doubt a little more than I would.

11:30 Blackmon: What’s the timeline for President Trump in your mind? I mean, is there a—let’s assume the Supreme Court nomination goes through, and there’s—this one big desire of Republicans is accomplished. But then, after that, at what point do large numbers of members of the House, in particular, begin to just stay away from President Trump? Or what would be the sequence of events that would keep them with him so that he doesn’t get in the same box that President Obama was in in 2010?

Kristol: I mean, it’s a very good question, and I think—I’ve looked a little bit at this historically, and I think it just differs with different presidencies. Some keep a sort of momentum going quite a while. He had—Obama’s had—Trump, rather, has had so little momentum in a way. His numbers are so low in terms of approval. He didn’t get his first big legislation through Congress, at least not yet, the Obamacare repeal and replace—that it’s hard—most of them get something through, like President Obama did with Obamacare, President Reagan did with tax cuts. Then you start to see a frittering away of the momentum and of the clout. With Trump, maybe the clout is still going to be exercised. He hasn’t really tried much, you know? He hasn’t really, you know, gone around the country, tried to rally support for something he cares about. And it’s unclear—I mean, he ran on immigration, trade, but what is he really doing on those issues? So, I really don’t know. I don’t know quite what they have in mind in terms of are they going to address those issues later and try to really rally people to their side? Are they going to attack Republicans? There was a little hint of that recently, where Trump attacked the Freedom Caucus members, and some of the people in his administration even said they should be defeated in primaries. Are we—are they really going to try that? I think basically, though, holding—I mean, Congress is very important. And President Obama losing the House in 2010, that was really the sign that he just didn’t have the ability to govern the way he did when he—obviously, when his party controlled both bodies.

13:18 Blackmon: Well, but you wrote today in The Weekly Standard of a crisis of confidence, nerve, and understanding that’s upon us. And you talked about that the work to avoid this done by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher and Bill Buckley, your father, Irving Kristol, Solzhenitsyn, Václav Havel—you are all over the place with this. The—

Kristol: Name dropping. (laughter)

Blackmon: Yeah, right, right, yeah. “They were successful, but now—I’ll be clichéd—Trumped.” And you say, with—“Here we are with demagogues as leaders, a civic culture as superficial as it is complacent. A domestic liberal order in incipient crisis. [A worldly?] order hanging on for dear life.” You sound like Jimmy Carter in 1979. (laughter)

Kristol: Yeah, well, Carter probably wasn’t wrong about the malaise. He just shouldn’t have said it as president, and he was probably responsible for it. But that’s a good comparison, because I think there it turned out—a lot of people thought the West was in crisis. One forgets that—in the late ‘70s. A lot of very learned books written about this. Solzhenitsyn’s speech in ’78 at Harvard was very much along these lines. But it turned out, actually, things were probably better than they looked, or it was easier to come back—that it—one would have thought. Reagan, Thatcher, Pope John Paul. I think there were a lot of major figures who turned things around, and then the Soviet Union was more kind of ossified and sclerotic than we realized. And so, we were able to win that in the ‘80s. And maybe that’ll be the case today. I really am—I just don’t know. I mean, it may be that we’re overreacting to Trump and to other things that are happening in Europe, and to the kinds of things that Charles Murray and Bob Putnam and Nick Eberstadt have written about in terms of men, especially—men and women, but especially men not working and working class problems and the challenges of technology and globalization.

FACTOID: Non-working men aged 19+ rose from 19% to 32% in last 50 years

But one does have a feeling that somehow these problems are a little deeper. It’s not just that Trump got lucky—which he did, I think—but, you know, in one 16, 18 month, you know, spurt, and then he became president—there was something deeper going on there. And I guess the thing that maybe, you know, sort of worries me the most is kind of a taking for granted—I mentioned complacency, I think, in that piece—taking for granted the successes of the last 70 years or so. I mean, it’s not nothing to have managed to sustain a liberal world order that’s been mostly peaceful. It’s allowed for an awful lot of prosperity for an awful lot of people, including Americans but also Indians and Chinese and others. I mean, it’s—the last 70 years have come—for a historian, do not look bad compared to the preceding 70 years, certainly, but compared to almost any 70 years. And incidentally, in the U.S., for all of our complaints, they don’t look that bad, you know? We’re a lot more just society than we were 50 years ago. We are a wealthier society. Economic growth has slowed down. Technology creates challenges. The gap between the educated and the less educated is harder in the modern economy to figure out upward paths and social mobility for the less educated. There are many problems. But there’s a little bit of throwing out the baby with the bathwater, actually.

16:10 Blackmon: Let’s go back a little bit to the—this—just this more general notion of the future of conservatism, the future of the Republican Party. This idea of whether the Republican Party is facing, essentially, 1964? [Kristol: Right.] And what I mean by that is that when Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act and he famously—some dispute this, but famously said to Bill Moyers that night, “I fear that we’ve lost the white South to the Republicans for a generation,” something like that. Whether he said that or not, it’s the case that the passage of the Civil Rights Act was a renunciation of one wing of the Democratic Party. It had never been completely acknowledged, but there were really two parties. Northern, urban party of unions and the white supremacist Democratic Party of the South. By pushing through the Civil Rights Act with—in an alliance with Everett Dirksen and other Republicans, it cleaved off the white Democrats of the South, who then—some version of them made their way into the Republican fold over time. Does that suggest that this moment has been coming for a long time, and the Republican Party, at some point, has to do the same thing, and essentially renounce that problematic wing of its following?

Kristol: Yeah, I think in some ways. And look, I think Republicans did renounce Pat Buchanan in ’99, 2000. And I was proud that Bush—I was happy to have him leave the party. And people forget—it’s all taken for granted now. Bush—when Gore had that—you know, that insane recount in Florida, Buchanan probably took more votes from Gore because of the weird, you know, Florida ballot stuff and all that. But at the time, I remember in—writing something in, I think, ’99 saying let Buchanan go. But a lot of people say, “Whoa, wait a second,” you know? There—he got 25 percent of the vote in some primaries in 1996, you know? And there—he’s speaking to a certain part of the party. And the Ron Paul—in 2008, 2012—I think won or ran second in a couple of early primaries. But McCain and Romney had nothing to do with his policies or—you know? So, I think the Republicans have been pretty good about renouncing that stuff recently. But I take—I very much agree. One reason, as a political matter, I think Trump could be such a disaster is, you know, he basically drew an inside straight to win this election in a whole bunch of ways. But, I mean, literally, in the Electoral College—or not literally, but figuratively in the Electoral College, you know, he got just the right votes from the right states that put him over the top, despite losing the popular vote by about two and a half million. Republicans have lost the popular vote to the Democrats six of the last seven presidential elections. Democrats have the groups that are growing, both in terms of ethnicity, but also in terms of youth and college education. You know, the—younger—older voters are dying off, younger voters are not, and—(laughter)

FACTOID: College graduates backed Clinton by 9-point margin in 2016 election

18:41 Blackmon: And white voters are declining.

Kristol: White voters are declining [inaudible] and non-college-educated voters are declining subject to the population as more and more people go to college. So, which would you prefer to be? The party of the college educated, less overwhelmingly white, and younger?

FACTOID: 55% of younger voters preferred Clinton, 18 points above Trump

Or the party of the opposite? Trump’s support is the opposite. So, I think Trump, in that respect, electorally—unless you were to broaden the coalition in a serious way, which he hasn’t shown much interest in doing or success in doing as president, could still. But if he doesn’t do that, I think it is a sort of one-off thing, probably. And then, the question is does the whole party go in that direction? As I—as you quoted me saying before, and I think I was right empirically in 2014, it looked sort of like it was going in another way in the other direction, you know, and I think had the ability to do that.

19:26 Blackmon: Charlie Sykes, conservative talk show host who has just retired, recently declared, last year, that—in a sort of self-revelatory moment said he and his fellow conservative media folks had been too successful in delegitimizing mainstream media. He said, “We destroyed our own immunity to fake news while empowering the worst and most reckless on the right.” And then, Jim Rutenberg recently had a piece in The New York Times about you stepping into the role of editor-at-large of The Weekly Standard and talked about the Standard as have—that it was part of this effort that succeeded in breaking the mainstream news media’s informational hegemony, but as it evolved grew and splintered, something else broke in a universal sense of truth. So, that’s sort of—that’s putting you guys and others right in with Fox News, and Ted Koppel telling Sean Hannity that they’re bad [Kristol: Right.] for America. But, I mean, is there some truth to that, that in this period of kind of attacking the underpinnings of mainstream media that a Pandora’s box of some sort got opened?

Kristol: Yeah, could be. I mean, everything has unanticipated consequences. That’s a big neo-conservative principle. And, no, but I mean Rutenberg, to be fair, in the New York Times piece there went out of his way to praise the Standard, really, for insisting on real facts, real news. Yeah, I do think there was a—maybe an overreaction, in a sense, to the liberal media, and then a sense—a lot of people—but I know a lot of people who are grateful to Fox for breaking up the monopoly, so to speak, and providing alternate points of view, and now think Fox has gone off the rails—so that you can think both things, right? National Review, which really was—is more conservative, a little bit. Bill Buckley’s magazine—more dependent on support of readers for its financial well-being, published the original Never Trump issue and took a lot of grief. I think lost, you know, 25 percent of its subscriptions. And so, they did this at some real financial risk, and they’ve stuck pretty well with that. They’ve moderated a little bit now that he’s president, I suppose. So, I—and the Journal had a—recently—editorial page—had a tough editorial [Blackmon: Right, right.] on Trump. So, you know, I think most of that world of conservative media has been—tried to be pretty honest and call it as they saw it, just as Buckley did in terms of the John Birchers and the—Buchanan later on, and denouncing things on the right that deserved to be denounced.

21:32 Blackmon: You seem to enjoy answering President Trump’s tweets and do that with some frequency. This morning, or overnight perhaps, he had a—he tweeted that with regard to the investigation into ties to Russia, the real story turns out to be surveillance and leaking. Find the leakers, that was one in a series of things. But in the—to that one, you responded, “This is uncannily like what Richard Nixon would have been tweeting in April 1973.” (laughter) [Kristol: Yeah, right.] That’s some—and then you said, “And Trump’s first term increasingly feels like Nixon’s second.” And so, the implications to all that are fairly obvious. I mean, are you just kidding? Or really think that?

Kristol: I partly really think that. I mean, no, I don’t know. I mean, Nixon—I think we only knew later—I mean, I was in college then, so I wasn’t following these things closely. And my impression is we only knew much later sort of how off the rails Nixon was in private in those last—year or two after some of the books came out, right? He was still president of the United States, and he dealt with various crises, the Yom Kippur War and other things, and seemed like a commanding figure. And, of course, Nixon had been vice-president and, you know, president for six years at that point—total—five years at that point—totally different from Trump in so many ways.

FACTOID: Richard Nixon served as Eisenhower’s vice president

Do I think it is possible that the Trump presidency could end up like the Nixon presidency? Yeah, I do. There’s a kind of conspiratorial mindset, a kind of paranoia, a kind of—the rules don’t apply to us, or the rules were made by the liberal elite, or the deep state, or people who are really hostile to us, and we need to end run them to be able to defend ourselves. And, I mean, and the leak thing I’m particularly amused by—I don’t know if that’s the right word. I’m struck by, because what was—how did Watergate begin, literally? Nixon hated leaks.

23:15 Blackmon: Last question: if you had to choose between the rest of the Trump presidency and four more years of Barack Obama, which would it be? (laughter)

Kristol: Yeah, that is tough. (laughter) I mean, I think—I will say, I unequivocally would choose President Obama as a human being in the White House in the sense of being a—behaving well and appropriately and with dignity, and in that respect not coarsening our public discourse. I had issues with some of the things, occasionally, he said and the way he sold the Iran deal and all. But that’s trivial compared to what Trump does. On policy, I do think Obama—in domestic policy, again, one can argue about—but I think on foreign policy, Obama’s reluctance to use—to commit the U.S., his deep desire to get out of the wars he inherited has led us to a very dangerous situation around the world. And in that respect, I actually think Trump, just because of his appointments, because of McMaster and Mattis and others, might end up doing better. But he could also end up really doing worse. Trump is a—you know, is a—there’s a wider spectrum of outcomes with Trump. I think I can sort of predict where an Obama presidency might go over the next four years. I don’t—I wouldn’t like it that much, and I think it could be pretty—not great for the country. But the kind of reckless and almost peremptory dismissal of the last 20, 40, 60 years—you know, we can’t do anything anymore, it’s all messed up, it’s terrible. The trade deals are terrible, the wars are terr—everything’s terrible. That is really irresponsible, because if people believe that, they lose any investment in securing this order. And, you know, maybe we shouldn’t secure it, I suppose, and maybe we can do much better, just on the fly. But I think you just don’t know—we have lost an appreciation of how bad things can get if you remove that kind of core American commitment to preserving a—both in security and in economics, this basic liberal world order.

Blackmon: Bill Kristol, thanks for being here.

Kristol: Thanks, Doug.

Blackmon: We hope you will join us for future editions of American Forum, where our focus is always on the presidency, and the urgent issues that face the nation. In upcoming episodes, Northwestern University Professor Geraldo Cadava on the future for Hispanics in today’s America, and John Farrell, author of the hot new biography of Richard Nixon. You can watch us on your local PBS affiliate. Or to join our ongoing conversation, look for us on the Miller Center Facebook page, visit our new, revamped website at MillerCenter.org, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is@douglasblackmon, Bill Kristol is @BillKristol. See you next week.