About this episode

March 19, 2017

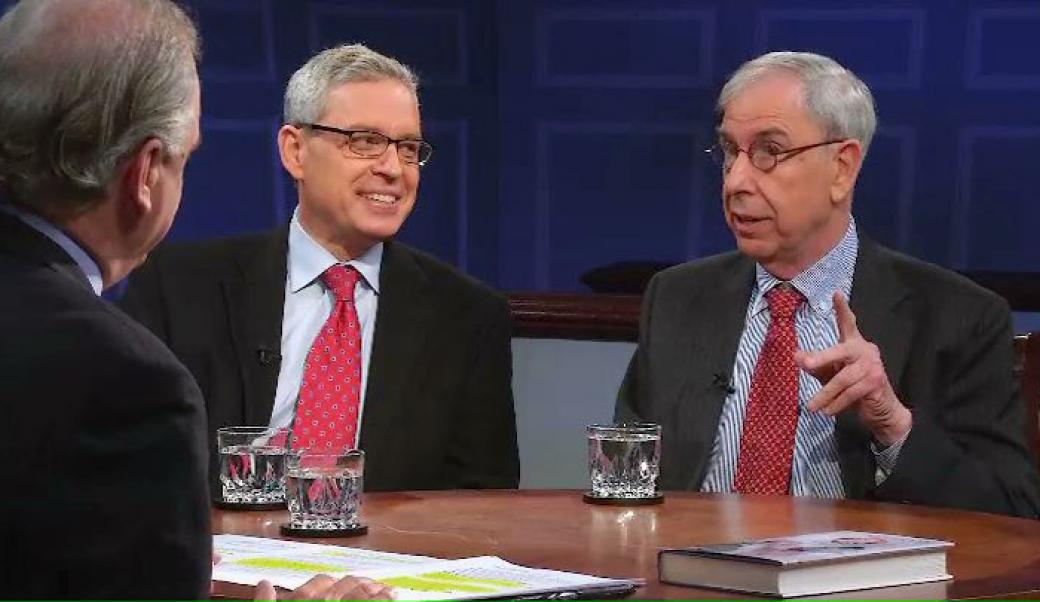

Sam Tanenhaus

We explore how traditional conservatives may react to Donald Trump's outsider triumph in 2016. Sam Tanenhaus is a contributor to Bloomberg View and writer at large at the British monthly Prospect. He was previously on staff at the New York Times, where he was editor in chief of both the Sunday Book Review (2004-13) and the Week in Review (2008-2010) and was also writer at large (2013-14).

Political Parties and Movements

Where do “classic” conservatives go after 2016?

Transcript

Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. In the aftermath of President Barack Obama’s historic election in 2008, it looked like American voters had decisively ended an era. Usually, that line is a set up for a discussion about how the election of an African American president showed that the United States was moving into a so-called post-racial society. That didn’t quite turn out the way many expected. But almost as dramatically, that election also appeared to signal a broad renunciation by a significant majority of Americans of the modern conservative “movement,” a seven decade long political phenomenon that dramatically reshaped politics in our country. Opposing central aspects of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal,” but then embracing social security and Medicare for hundreds of millions of Americans. It resisted “big government” and national debt, opposed the Civil Rights Movement—but ultimately was crucial to the dismantling of segregation. It gave us Richard Nixon—and the scandals that attached to him. It delivered Ronald Reagan—with both his buoyant optimism, his victory over communism, and also his staggering additions to the national deficit. It gave birth to the Bush dynasty—and its historic peaceful unwinding of the Soviet Bloc, and also the disastrous invasion of Iraq, destabilization of the Middle East, and the financial crisis of 2008. But then the victory of Barack Obama—coupled with giant changes in the racial demographics of the country—convinced many people—including some top leaders in the Republican Party—that the end of conservatism as a political movement might be at hand.

FACTOID: The Question: is the Conservative Movement winning or collapsing?

And yet: now we have President Elect Donald Trump. How does it all add up? Our guest today is Sam Tanenhaus, a celebrated writer and political observer, whose 2009 book,The Death Of Conservatism: A Movement and Its Consequences. Simultaneously declared conservative politics to be on life support, while also offering a formula for its revitalization. His books and articles have appeared, everywhere, and he is currently at work on a biography of the legendary conservative thinker and journalist William F. Buckley, Jr. Thank you for joining us.

Tanenhaus: Pleasure to be here.

3:03 Blackmon: So is Donald Trump the rebirth of Conservatism that you were imagining, eight, nine years ago?

Tanenhaus: Believe it or not, he could be. Donald Trump flourished for a longtime outside of what we think of as a conservative movement. Small government and very much about a set of ideological principles that were articulated or annunciated much more by someone like Ted Cruz than there were by Donald Trump during the campaign. Trump was repeatedly accused by many Republicans and conservatives for not being either a true Republican or conservative; Ted Cruz you may remember said “Donald Trump will give us a politics to the left of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. “

Blackmon: And New York values.

Tanenhaus: Very much New York values, and there he is the spokesman for the forgotten America living in a triplex in midtown Manhattan. So in a sense what Mr. Trump has done, President elect Trump has done, is further blow up conservatism and the Republican Party from within, and that was the outcome very few myself included saw.

FACTOID: Trump has registered with GOP, Independence party and Democrats

4:13 Blackmon: Does Donald Trump represent conservatism or does he represent something that reminds us of conservatism, but really fundamentally isn’t? I mean is there a connection between, what would Buckley say to Donald Trump?

Tanenhaus: Actually we know what Buckley would say because he said it in 2000 when Trump was first considering running for president.

FACTOID: William F. Buckley, Jr. founded National Review in 1955

Bill Buckley wrote a piece, I love were it appeared, Cigar Aficionado. Buckley liked Philippine cigarillos, long thin cigars, and he actually wrote a piece about Donald Trump because Trump was considering running, and he was quite critical of him and said at one point well what does Donald Trump have to offer. He said he has to offer himself as a business man, he said that counts for something but in the end not really all that much. And the danger is, this is he said, a narcissist, and a narcissist falls in love with his own image. And this is not what American politics needs. Now having said that I also wrote a small piece for Esquire Magazine and said in other ways Buckleyism and Trumpism are quite similar. Bill Buckley also wanted to dynamite the Republican Party that he knew, which was the party of Dwight Eisenhower. Which was internationalist and perpetuated the New Deal. This is in the 1950s when Buckley founded in the National Review almost exactly 61 years ago. It was in the fall of 1955. He said “We need radical conservatives who are more ideological, but also who will also take on the establishment.” And in that sense Trump doesn’t fit the ideological part, but the antiestablishment part he does. When Bill Buckley ran for mayor in 1965 he made a number of quite polarizing racial remarks that would remind us of Donald Trump. And what attracted many to Bill Buckley then and attracted and still attracts many to Trump today is the idea that he says what’s on his mind. He may not be right, he may not be factually accurate, in fact he could be the opposite of those things, but he’s not censored. And I think something that grew up in our politics and culture, and the two are inseparable in America, politics and culture go together, and you know this you’re a great historian of slavery and post slavery, and what we think of as policy often turns into feelings and emotions; Trump was very good at that. What Buckley tapped into, way back in the ’60s, that’s still with us, is the idea that there are many people who consider themselves honest hard working decent Americans, who are who are marginalized within the culture, and that’s what Trump is about too I think.

7:12 Blackmon: He’s been talking a lot about in his transition period about infrastructure as a sort of fast action response that he might make, but part of what’s interesting to me about that is that infrastructure is something, it’s not that the Democrats are now picking up Trump’s call for infrastructure, but it’s that the Democrats have been talking about a infrastructure program, from since the transition before Obama came into office. And it was vigorously opposed by the Republican Congress. You pointed out at other times, when the book when it came out in 2009 you were really writing about the first year of back and forth between the new president Obama and the Republican Congress, but for instance if we go back and try to remember the big stimulus package that was pushed through to try to push through to jump start the economy, Republicans criticized it for not having a dimension related to small business so Obama came back and proposed 30 billion dollars of tarp money for small business and the Republican Congress attacked this as a complete betrayal and this sort of wild eye idea although it was exactly what they had been saying was what we needed. Now we have Donald Trump picking up Obama’s infrastructure plan, when he’s been talking about immigration lately, and deporting the criminal illegal aliens, well that’s been the Obama policy. That’s why Obama has deported more people than anybody else in history. So it’s very confusing.

FACTOID: GOP blocked Obama on hundreds of billions for infrastructure

Tanenhaus: It is and some other things. Student debt, right before the election Donald Trump was making very liberal noises about that and also health care.

8:50 Blackmon: Yeah preserving certain signature dimensions of it.

Tanenhaus: He met with the president and suddenly he realized there were previsions of it the wanted to keep. It can be really frustrating for a liberal I think because what a liberal might see is all the hypocrisy in all of this. Well that’s what a lot of politics is. One of the great political thinkers Gary Wills wrote long ago, that this successful political leader, he was really picking up on something Walter Bagehot, the founder of the London Economist wrote in the 1850s, that the best political leaders are actually a step behind the best thinkers They’re more in tune with the public and they’re ready to move when the public itself is ready to move. So they can sometimes seem not all that creative or imaginative, because there are other people out there who move ahead. Okay we could see somebody, if we set aside partisan divides which is very hard for us to do, but Donald Trump repeatedly would refer to Bernie Sanders as a kind of comrade in arms of his, he did it all the way through the last debate. Well if we look at Senator Sanders as the one who was out in front on a lot of these issues in the campaign. Along with Elizabeth Warren, but she elected decided not to run. Bernie Sanders is the one who was talking about putting America back to work, raising minimum wage, retiring all student debt, all these issues, and then you see well, Trump has come around, the Republicans have come around and maybe they’re looking at some of these things. Then our politics looks less dysfunctional and less a matter of, well who is hypocritical because they said this thing in one month and changed their mind six months later, it looks more like the kind of give and take that we always say we want. I’ll add one other thing too is back in the days when it looked as if the demographic shifts in the country favored Democrats we heard a lot about the virtues of the electoral map, because all the big states were going to Democrats, well Donald Trump kind of blew a hole through that electoral map and suddenly we have lot of people on the left wondering whether the electoral college is really the answer, and that happens on all sides, and that’s how politics works and we have to accept that. If you live in a world with pure principle, you’ll win a lot of arguments but you won’t get much done.

11:23 Blackmon: Though the idea of a fairly open anti Semite who has played footsie with Neo-Nazis for a very long time becoming the unelected potentially second most powerful person in America one does wonder if that will not at some point register on a broader constituency of Americans that maybe that’s problematic—but maybe not.

Tanenhaus: Well it’s hard to know where those things, Doug, I just happened to watch Alan Dershowitz on television saying well, he was talking about Steve Bannon, I think, well we don’t really know whether he’s anti Semantic or not. One thing I do know is that a very long account in New York Magazine about his divorce proceedings in which his wife when said they were shopping around for very tony private schools in Los Angeles Bannon asked whether there really should be so many books about Hanukkah on the library shelves. I thought if this is really what we’re talking about, a remark he might have made about books on Hanukkah in a prestigious, elite boarding school in Los Angeles, this is what our problem was during the election. Is that there was a lot more talk about that than there was about the country at large. You know, another thing I’ve been thinking about is much of our political discussion, much and a lot of it in the democratic party, and among liberals, is about climate change, which is really important, it's a hugely important issue. But, you know, in addition to climate in this country, we also have geography.

FACTOID: Trump has previously called climate change a “hoax”

And there's a lot of America that doesn't get talked about by people like me. We talk about gender, we talk about race, we talk about transgender, we talk about people's sexual choices, but we don't really talk about our coastlines and rivers, our prairies and plains. American culture, American history, is built into its geography. The New York Times had an interesting graphic right after the election that showed, if the Donald Trump map, if you look at it geographically, he won 80 percent of the counties in America. Well, there's a lot of America that isn't Manhattan, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. And do most of the people live there? Yes, many people do live there, and every person gets his or her or their vote, as we now say, but there's also this great sort of heartland of the country, which I spent a number of years in, I lived in the Midwest for much of my life. I went to collage there, my daughter went to college there, when I was a child I lived in Iowa. That's America too. And there was a sense, for a long time during this election cycle, where you were going to be measured, as either a politician, for any office, quite apart from the presidency, or as an observer and commentator, on, you would be measured on the kinds of microaggressions, as they call them, you might be committing against people because you use the wrong vocabulary.

14:37 Blackmon: I want to hear your thought though about, more specifically back to the progress of conservatism. I'm of the view that a big element of what has happened in American politics is also that the invasion of Iraq, in ways that we still fail to fully comprehend, that when it turned out, however one wants to characterize it, I think the only clinical way to characterize it is as a disaster. There's really no way to view it as anything else, based on facts. Um, but the, regardless of how one terms it, it clearly was something that turned out, a lot of people died, in what started off as something swathed in patriotic meaning.

FACTOID: Since 2004, majority of Americans have said Iraq invasion a “mistake”

And certainly, everyone who served there was acting out tremendous patriotism and bravery. That struck me as something that cracked the sense of confidence of a lot of conservatives, people who would call themselves conservatives, uh sort of their set of, sort of faith that, well if the president sends our men and women off to war, I can believe that that's the right thing. That's so momentous a thing. We wouldn't get that wrong. And I think that then, when it goes so terribly wrong, that's both a part of why Barack Obama gets elected President, but that's also part of why, even more so, there was a big population of Americans who were ripe, even more ripe, for the idea that you just can't trust any of those people. And that that's another huge element of this readiness of a lot of Americans to say, "Okay, I'll take this other guy because I just like the way he talks. I like the way he says "Screw you" to everybody who has specific expectations of him.

Tanenhaus: Not only that, in the South Carolina primary debate, he very directly said. It was one of the few sentences Donald Trump completed. You know, sometimes he sounds like Molly Bloom in Joyce's Ulysses. He's kind of going form phrase to phrase, and it's a sort of stream of consciousness. But this time he said, he lied about the war in Iraq. They said there were weapons of mass destruction, and there were none. You can see it in the transcript. He said it in South Carolina with all those military bases, with all those strong supporters of the Bushes, and he finished Jeb Bush off in that primary. So Trump comes out of that, politics as well. Many years ago, oh I'm sorry, you want to say something.

17:10 Blackmon: I was just going to say, since we're on that, Trump at another point, just before that, said that 9/11 was the fault of George Bush, that the attack was allowed by George Bush. Not just that the invasion was a bad idea, but that he was to blame for the 9/11 attacks.

FACTOID: In GOP debate Trump blamed 9/11 on Bush and President Bill Clinton

Tanenhaus: Which is something many Democrats had said. Um, in 2007.

17:34 Blackmon: Which, by the way, I'm sorry to interrupt you, which of course, the former of those, I said before, I just want to keep the record straight, I said before there's no way to refer to the invasion of Iraq factually as anything other than a disaster. At the same time, since we're being factual, obviously 9/11 was not George Bush's fault. That was an outrageous and deplorable insult to President Bush for it to have been said. There's no factual basis to that whatsoever. I want to keep clear that, while I'm criticizing President Bush on one thing, that certainly no sensible person would attribute 9/11 to President Bush.

Tanenhaus: No, no, the only question that came up is whether there had been intelligence briefings, he wasn't attending to as closely as he might have. That's something that happens with a lot of presidents.

Blackmon: But back to the observation you were making.

Tanenhaus: Well in 2007, I think it was, when I was interviewing Bill Buckley, who died not long after that, I said, well is Iraq the Republicans' Vietnam? And he said, yes, that's what it is. And his concern was that President Bush didn't seem to have a plan B. Because part of the classic conservative argument we've been discussing, the theory is of adjustment and flexibility. That's the incrementalism you mentioned. And there the problem seemed to be that many of Bush's advisors, I wrote about this at the time, were what we think of, or call, neoconservatives. And they had a very clear, stark version, a Manichean, version of, vision, of how the world worked, much of it based on the history of the Holocaust and the rise of fascism and communism, and also on our victory in the Cold War. And they wanted to apply that template again in Iraq, and it didn't work. One of the interesting things about Trumpism that was mentioned early on, and has gone away, is his America-first ideology, which is seen as radical, and in some ways is, but that actually goes back to where Republicans were before World War II.

Blackmon: Father Coughlin.

Tanenhaus: It was called, Yeah, it was called the Old Right. Its leaders, people like Herbert Hoover and Robert Taft, did not want the United States involved in foreign politics, and certainly not foreign wars, as they called them. There was an enormous movement in this country, of left and right, that opposed intervention in the second world war. There were liberal students on ivy league campuses who were leading that protest against the invasion, until Pearl Harbor happened, against our intervention in second world war. When Trump speaks that language, he's actually pulling it out of an older conservatism that predates the conservatism we're talking about, which is really a Cold War conservatism. So, in that sense there is a resonance to what he says. Also, of course, with the tariff and trade policies. Those go back to someone like William McKinley. It interested me that Karl Rove, who was very critical of Trump early on, wrote a book about McKinley, and one of McKinley's big policies, was tariffs, was protectionism. And so, we shouldn't be surprised when this resurfaces in our conversation, and it's another instance in which, again, Trumpism, if not necessarily Trump himself, speaks to broader currents in our history.

21:04 Blackmon: Um yeah, there was a statement form President-elect Trump's spokesman early in the transition period, where there was criticism of Mr. Bannon as a chief advisor, and then there were reports of chaos in the process, and Governor Christie having been fired from the transition process. And a statement came out from Mr. Trump's spokesman specifically saying, it's an orderly process...he and Trump himself sent out a tweet that said, "This is an orderly process. I'm the one, only one who knows who the finalists are and I make these decisions." But then the spokesman came out and said…and said, "Good choices are being made, and these are all going to be leaders who will put America first," uh, and, bringing back into the dialogue the America-first language, which he also used in uh, used in his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention. Very Father Coughlin kinds of phraseology in the speech, so.

FACTOID: Father Coughlin was anti-Semitic priest with 30 million radio listeners

Tanenhaus: Well if you remember Rand Paul when he emerged briefly as kind of the breath of new thinking and argument in the Senate, was very much about what some would call an isolationist, a non-interventionist foreign policy. And after the election he was saying it again as far as foreign policy goes that one reason that he had supported Mr. Trump was because he was opposed to democratization and crusading projects as we remember George Bush once told us he was too.

22:31 Blackmon: We know from reporting that another similarity between President Trump and most Americans is that he doesn’t read books, like most Americans. And the uh, yours is a slim volume though. We often ask a version of this question but after the inauguration if you got the call from President Trump that said I heard about this book you wrote that declared conservatism dead and offered an autopsy on it. Give me a few lines of advice on how I can be the messiah who resurrects conservatism.

Tanenhaus: It would be actually to stay true to the base of voters who elected him. Listen to them. They’re people who want to be included and it seems odd because in some sense they are still the majority, not the majority in electoral terms but hey if you’re going to Balkanize the country, I have told people this for a long time back when things were really divided racially and ethnically, if you’re gonna line everybody up in the high school gymnasium by ethnicity and gender guess which line is still gonna be the longest? Ya know it’s gonna be, it’s gonna be the white line right? Might be more white women than white men, but those are the groups that Trump won. There’s a lot of the country that supported him but they’re not necessarily the evil people they were being, the basket of deplorables, which I think is one of the shocking statements made in our politics in this past election. Almost as bad in its way as anything Donald Trump said because of language, the language of superiority. Actually taking an adjective and using it as a noun, I mean not to be, I mean you know as head of the New York Times Book Review we’re always fixing people’s language. Not to be too much of a geek about this, but when you take an adjective and turn it into a noun. When you say that something is a deplorable, that that person is a deplorable you’re making a kind of cultural statement in a language that is alien to many people, that’s like what the progressive left needs to stop doing. What Trump on the other side needs to do is say you know what it’s not just about the things you’re mad about it’s about the things you aspire to that we’re going to help with and that’s how he makes his Republicanism, his rust belt Republicanism if that’s what we’re going to call it, a more positive, forward looking thing.

Blackmon: Sam Tanenhaus thanks for being here.

Tanenhaus: My pleasure Doug.

Blackmon: His book is The Death Of Conservatism: A Movement and Its Consequences. If you’d like to send us a comment about this episode or join in our ongoing conversation about the big issues in American life, or watch a live recording of our next episode go to the Miller Center Facebook page, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. For a transcript of this dialogue, or to watch other episodes, visit us at: millercenter.org/americanforum. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you again next week.