From the director: How to assess Joe Biden's first year

We take presidential "first years" seriously at the Miller Center

As President Biden completed his first year, the Miller Center hosted a two-hour webinar, featuring Democratic, Republican, and independent practitioners and scholars who assessed his performance.

That’s also why I’ve spent the past two weeks in private conversations with two dozen individuals—a bipartisan list of senior government officials, journalists, members of Congress, think-tank researchers, political consultants, and nonprofit leaders. The interviews were conducted by 10 terrific UVA undergraduates, as part of a class I co-taught on President Biden’s first year.

The collective assessment?

Lesson one: Context matters. Presidents must play the hands they are dealt. Our greatest leaders rise to monumental challenges. The three presidents regularly heralded as our best—Washington, Lincoln, and FDR—faced some of the most tumultuous moments in American history.

So what has been the context for the Biden presidency?

Severe, simultaneous, and overlapping crises.

Even before the 2020 election, we saw that whoever won office would face perhaps the greatest confluence of crises in American history. The pandemic and economic reverberations are our most immediate, biggest challenges, with hundreds of thousands dead and millions having lost jobs. That combines with our deepening crises of democracy, most notably the violent effort to overturn the 2020 election.

On top of that, most Democrats and many Republicans also see a racial justice reckoning and a climate crisis.

Taken together, these overlapping crises would challenge any president. Each is a domestic challenge and is also connected to great foreign dangers.

Lesson two: Presidential leadership matters. Whether you agree or disagree with any particular president, the decisions they make, and how they make them, are critical to all of us.

Biden is trying to return to a more orthodox use of presidential powers. His theory has been that a more traditional president—a normal president—can right what’s gone wrong in the country and bring us together.

Lesson three: Unity is more challenging than he and others assumed. The hard news for the president is that, despite the massive efforts he already has overseen, he has been blown off course. The good news is that he still has time to adjust.

Unity mission

Let’s start with President Biden’s overriding goal: Unity. Biden launched his campaign by claiming his mission was to “restore the soul of America.” He pointed to the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville.

As the pandemic unfolded and he secured the Democratic nomination, he expanded his priorities to include a series of overlapping crises: the “once-in-a-century virus… [that] has taken as many lives in one year as America lost in all of World War II”; the economic crisis where “millions of jobs have been lost”; “a cry for racial justice”; and “a cry for survival … from the planet itself.”

Two weeks after the January 6 insurrection, Biden put these other crises as subordinate to a higher calling: preserving a fragile democracy and restoring national unity. And he reemphasized that calling in his inaugural address one year ago.

With that higher mission in mind, we can see how the president is both succeeding and struggling to address these simultaneous crises.

Personnel and process

In both the public Miller Center webinar and many of our private conversations, Democrats and Republicans gave the administration high marks for bringing professionals back into government. That assessment should not be surprising, since the bulk of our interviewees are policy and political professionals. Many of the Republicans served in the George W. Bush administration. They all value public service.

Democrat and Republican alike also pointed to the restoration of basic processes of government as an accomplishment. That includes ramping up the nominations and confirmations of senior positions. It also has included elevating career civil servants and setting records on appointing women, African Americans, and other minorities to key positions.

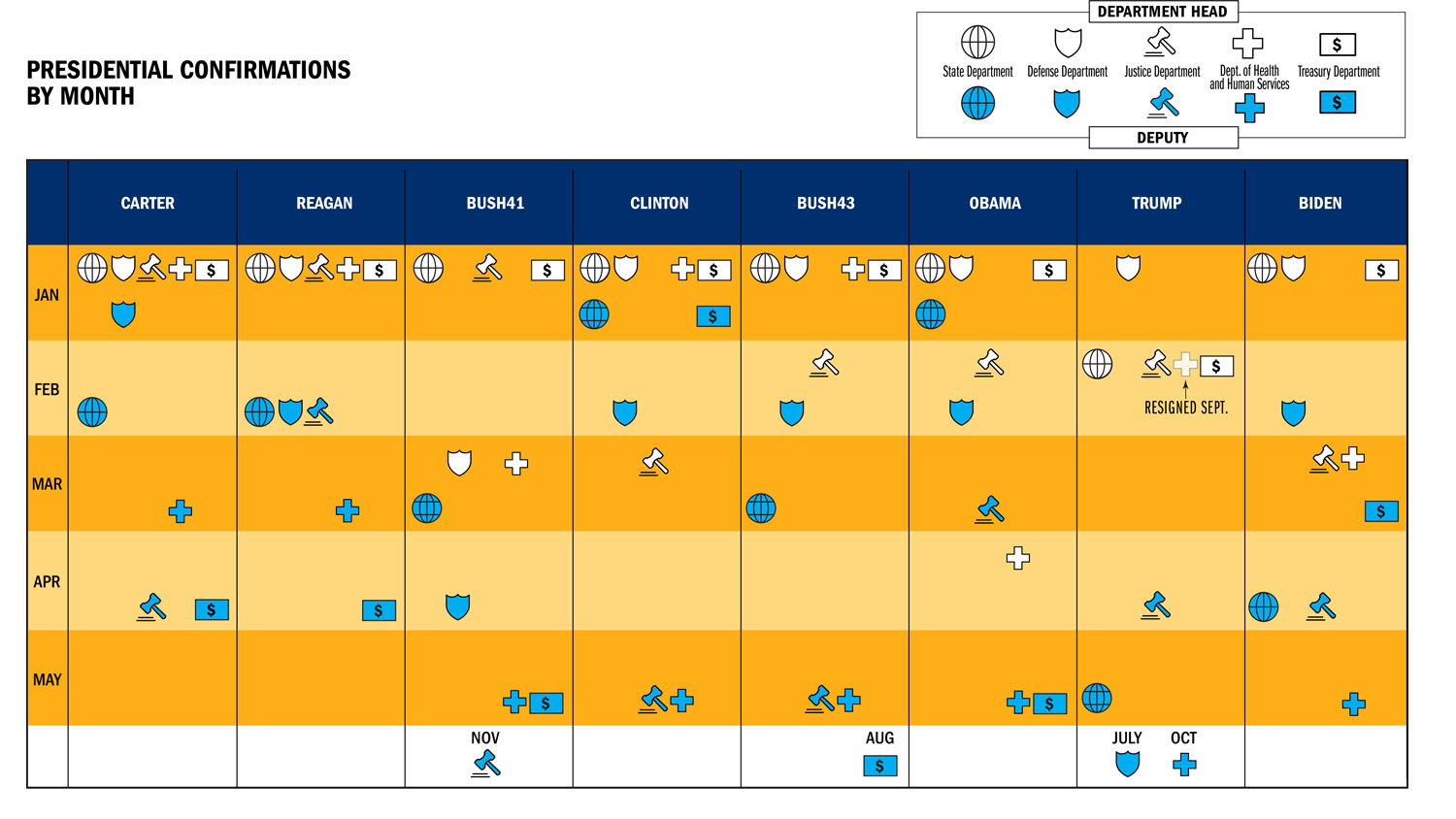

The administration staffed its cabinet secretaries and deputies within the first 100 days, roughly on pace with recent predecessors and ahead of the Trump administration.

Still, the government’s most important positions remain only slightly more than half full—even though the administration has nominated people for most of the 1,200 confirmable appointments. According to the Partnership for Public Service’s Transition Tracker (which follows about 800 of those positions), 186 nominations remain stuck in the Senate and another 146 are without a nominee.

Perhaps not surprisingly, as the year progressed, both Democrats and Republicans pointed to process failures in the administration. Regardless of how experienced each member of the team is—as is true in every administration—working together in this team is new.

Operating under pandemic conditions—with limited in-person meetings and a bevy of crises—has hampered the administration’s ability to perform. And ironically, despite the diversity of the Biden team, some criticized the administration for being too insular and like-minded.

Priorities and politics

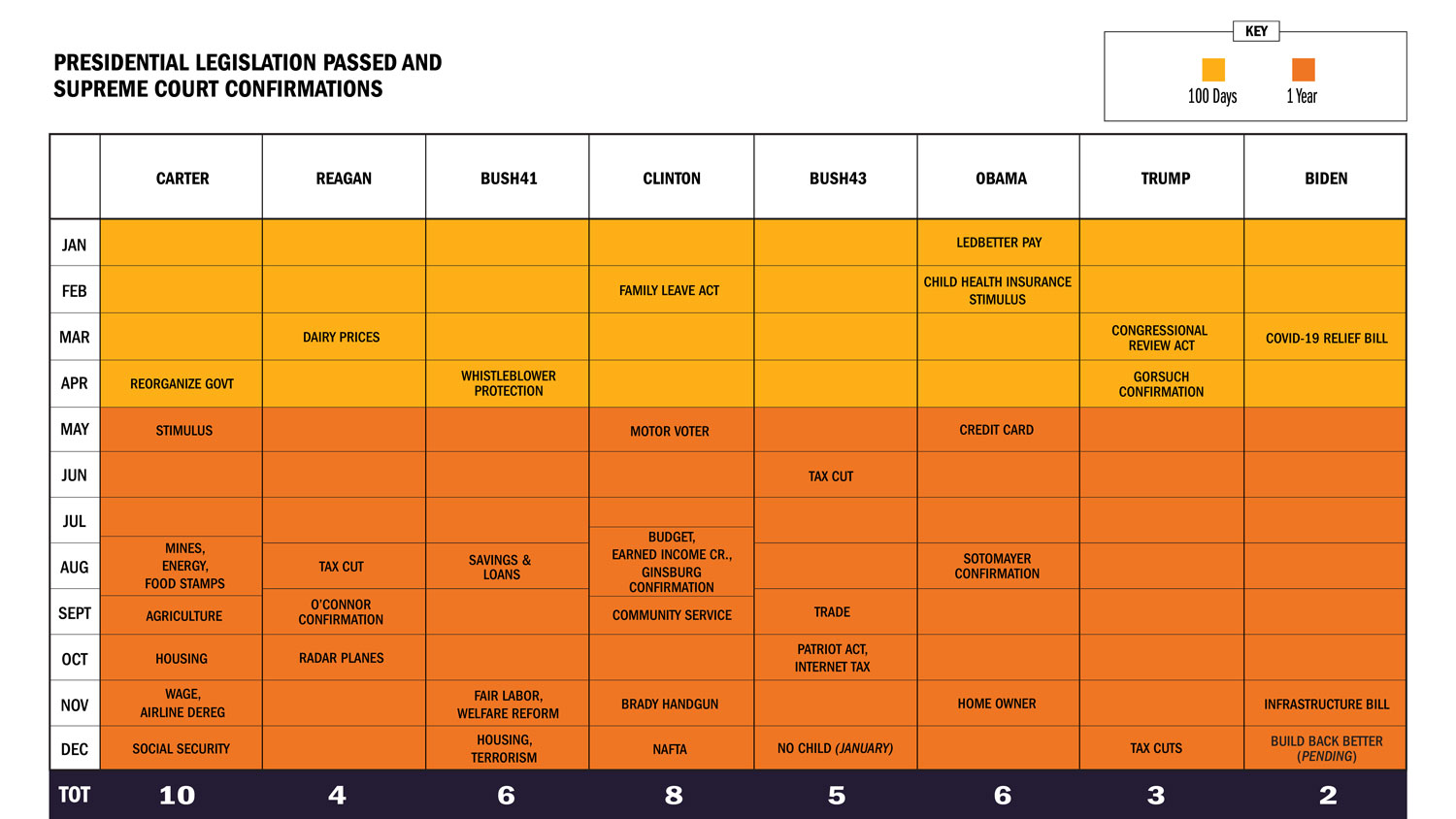

The biggest opportunity in the first year is to move on a legislative agenda. As Miller Center Senior Fellow Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, who is also the senior research director for the White House Transition Project, told us last week, presidents can use the year to secure legislative wins, especially when a president’s party controls both houses of Congress. After one year, members of Congress start to focus on their own reelection, making it harder to win votes on difficult issues.

Of course, much of this is beyond the president’s direct control. Just because the president’s party controls Congress doesn’t mean the president controls Congress. As Miller Center Professor Guian McKee pointed out, this is only the third time that a new president has started office with an evenly divided Senate. That means Democratic control is always one vote from reality.

Josh Bolten, former chief of staff to President George W. Bush, argued that presidents should try to govern with the same agenda on which they campaigned. But the transition from running for office to governing also means narrowing the list of things that can be done legislatively.

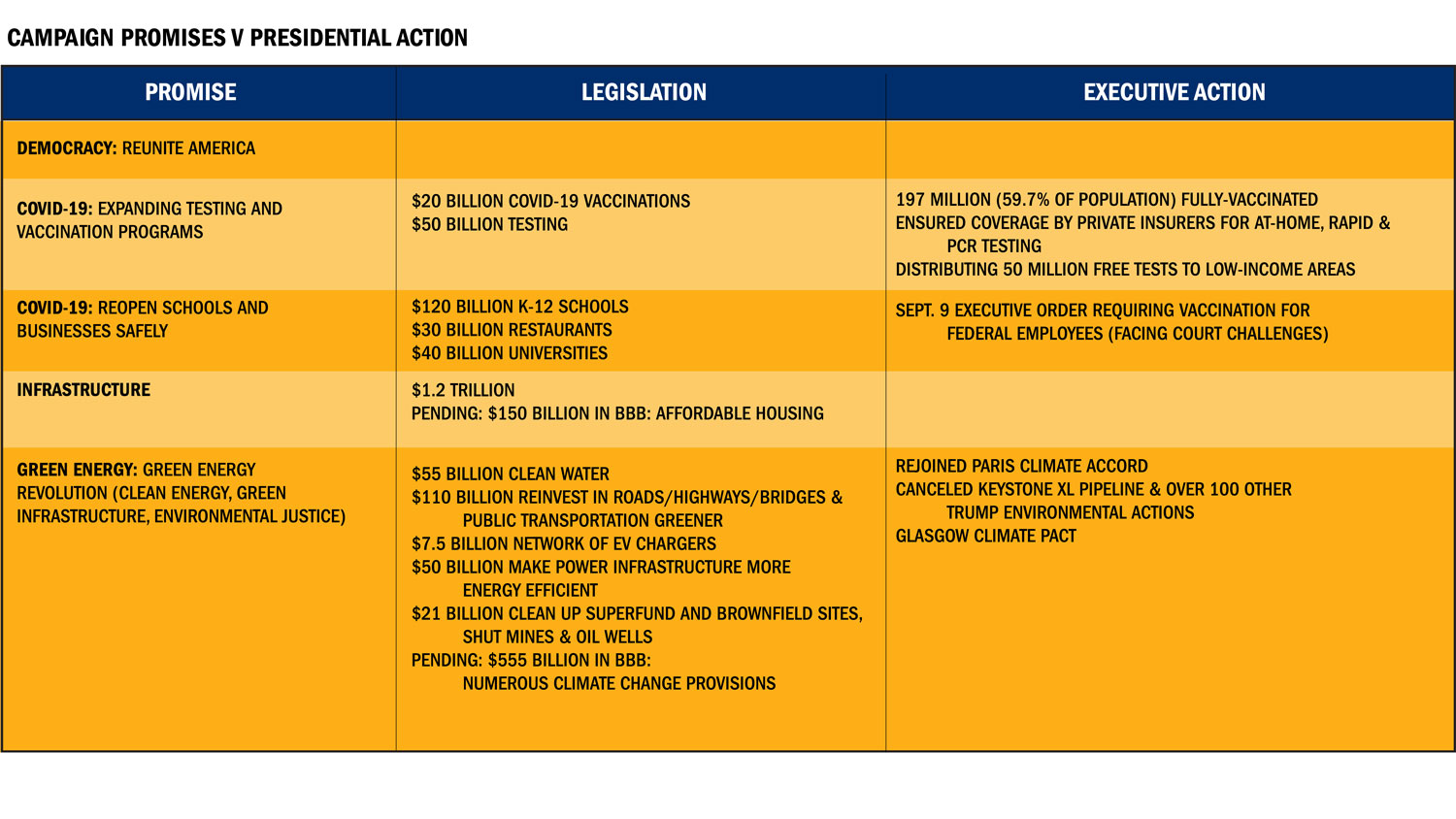

President Biden’s early wins in crisis management are indeed historically important. In addressing a pandemic that had already killed 500,000 Americans, he sought and passed a $1.9 trillion COVID response bill. And in facing deeper challenges to American economic growth, he followed that with the signing of a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill in October.

Already, those two bills stack up against accomplishments from other presidential first years in recent history.

Going beyond legislation, the president and his team administered immediate COVID related efforts, in particular massive vaccine distribution, saving thousands of lives. Economic growth and jobs have been restored, albeit with newfound companions of supply chain disruption and persistent inflation.

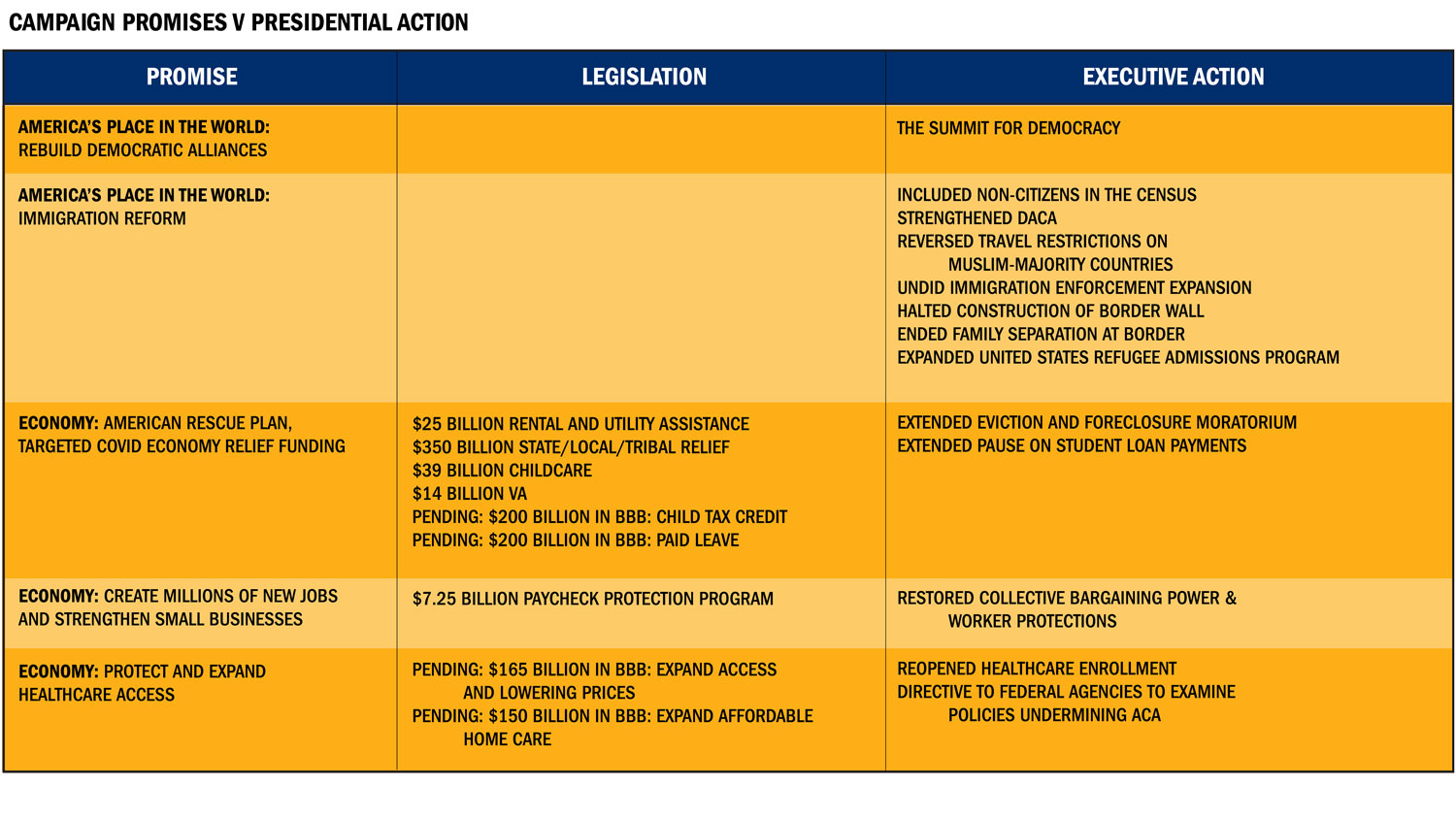

Biden has used executive authority to advance a long list of campaign promises both abroad and at home: from coordinating more closely with allies, to returning to the Paris Climate Agreement and negotiating the next stage of greenhouse gas reduction commitments at Glasgow, to a series of administrative measures on immigration and health care.

Not all of these are universally popular. But they follow a pattern of “executive centered partisanship,” noted by the Miller Center’s Sid Milkis. Since legislation is increasingly elusive, the president uses executive action to carry out his party’s agenda.

Still, the administration’s strong start gave way to a sense of incompetence. That began in the summer, as the premature declaration of victory over COVID was overtaken by the Delta variant and then Omicron. Complex issues—such as U.S. efforts to share the vaccine around the world—led to political division at home and anger abroad. That shortcoming is now causing a near-certain outcome of wider global spread of the disease, which could bring even more challenging coronavirus variants, our Schlesinger Professor Steve Morrison told us.

The COVID surge was taking place just as the withdrawal from Afghanistan caused a tragic collapse. On the one hand, national security crises are quite common during a president’s first year: Bay of Pigs for JFK; Tiananmen Square and the Berlin Wall for George H. W. Bush; Black Hawk Down in Somalia for Bill Clinton; September 11, 2001, for George W. Bush.

On the other hand, this crisis contributed to a sense of not just incompetency but also indifference. And as our own Eric Edelman and Brookings’s Suzanne Maloney told our webinar audience, it has signaled to our adversaries—Iran, Russia, and China—a broader message that America’s domestic divisions mean that we are pulling back from our global engagement.

Moreover, the Afghanistan collapse took place just as Biden was expanding the domestic agenda further than could sustain unity. He sought (and still has failed to pass) his social infrastructure bill, Build Back Better.

Rather than restoring faith in American democracy, the failure to secure one more win is leading to a vicious circle in public trust. Despite having praised many of the more conventional parts of Biden’s first year, Bolten told us, “They tried to cram through too much of their agenda… I think they have overreached.”

As the year ended, Biden returned to the core message that launched his campaign: Restore the soul of American democracy. In December, he fulfilled his campaign promise to host a Summit for Democracy. And in the final days of his first year, he renewed his effort to pass domestic voting rights legislation, even if he turned up the rhetoric further than many moderate Republicans felt appropriate.

That effort unites his party, but not so much that Senate moderates are willing to amend the filibuster rules that stand in the way of voting reforms. Unity appears elusive. And the president appears responsible.

Popularity

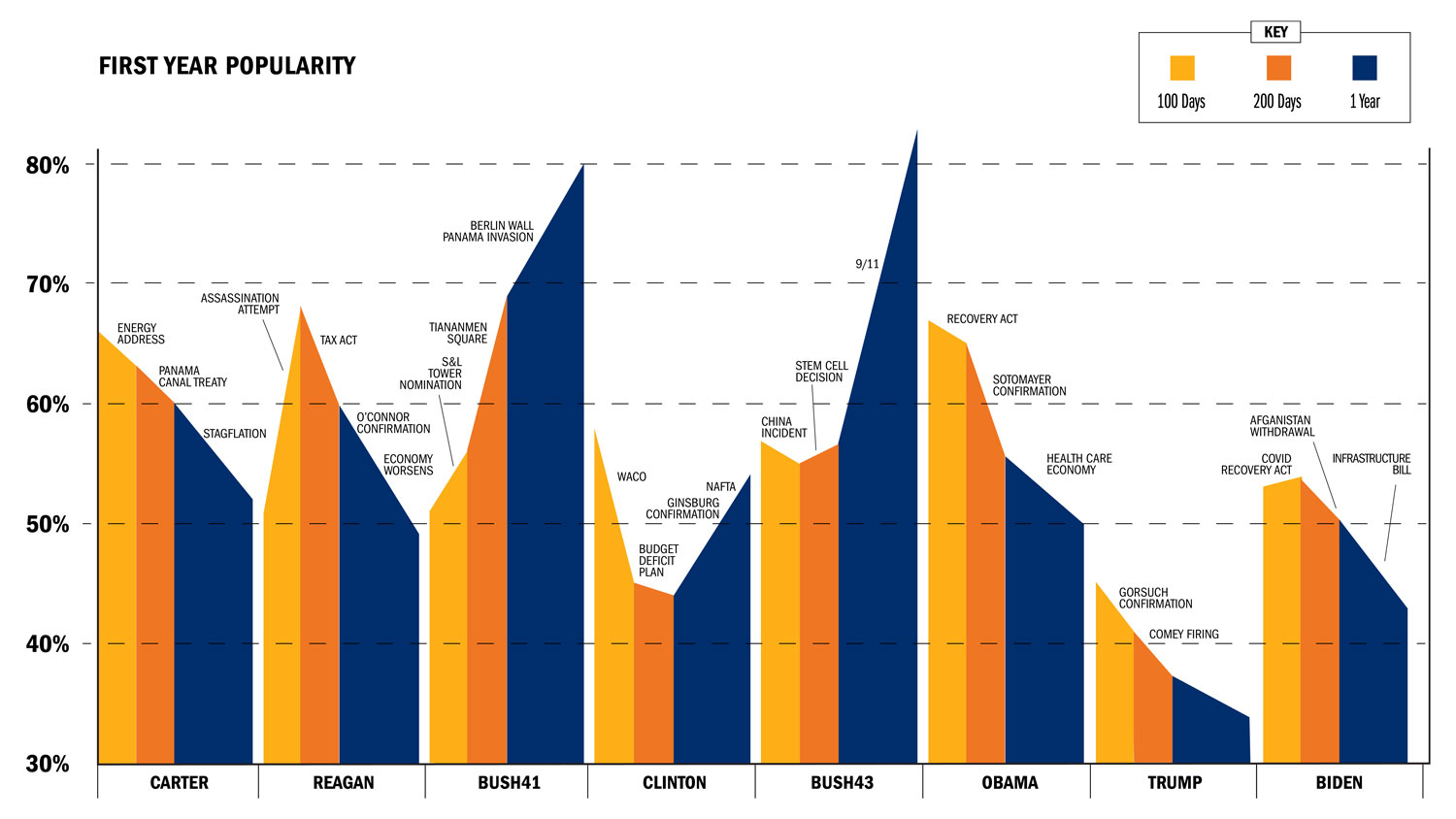

President Biden’s travails can be seen in his job approval rating. The early successes meant growing support for his leadership. He was making good on his promise of unity. As the summer wore on—and as Delta and the Taliban simultaneously surged—Biden’s numbers fell. The president who had declared independence from the pandemic in July was being personally blamed for the shambolic opening of schools in September. Not even the bipartisan infrastructure bill could counter that trend. He ended the year with an approval rating below the 50 percent threshold. While that’s been true of a few other presidents, notably Ronald Reagan, it does not bode well for his party heading into the upcoming midterm elections.

Can the president correct course? Opinion remains divided. Most observers feel that Democrats are likely to lose one or both houses of Congress in the upcoming midterm election—an outcome that also befell presidents Clinton, Obama, and Trump.

Judging by the past week alone, Biden and the bulk of his party seem committed to achieving smaller legislative accomplishments on just parts of his larger bills. Their thinking seems to reach a compromise within their party, pivot off a final legislative victory, and then claim a broader success if the economy fully recovers this summer, assuming inflation comes down.

Republicans are skeptical. As Bolten, a Republican, told us: “I don’t know whether there’s much opportunity to recover . . . if Biden becomes more of the centrist president that most people thought they were voting for when they elected him. But that may be the only path to significant accomplishment in this second year, and especially in the third and fourth years, when the president is likely to be facing at least a Republican House.”

Perhaps the one saving grace has come from what has been a core theme of Biden’s five-decade career: patience.

In retrospect, the president seems now to have been too eager to declare victory on COVID, to withdraw from Afghanistan, and to antagonize his opponents on a broad voting rights agenda. But he also has demonstrated personal patience with Senate moderates from both parties over the course of the year, and he might usefully fall back on that.

As his first year turns to his second, Biden may have one final opportunity to demonstrate unity. How he pursues that could make all the difference.