Election 2024

University of Virginia experts offer frequent updates on the latest election developments

The last time the Senate voted down a cabinet nomination

Miller Center Senior Fellow Robert Strong recalls the failed nomination of John Tower

It was 1989, and President George H. W. Bush had nominated John Tower to be secretary of defense. Tower was Bush’s friend, political mentor, and a former senator from Texas. Unlike the current controversial Trump nominees, there was no serious question about Tower’s qualifications to lead the Defense Department. He had been chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and was widely regarded as an expert on national security. There were liberal critics of Tower’s robust support for the Reagan military buildup, and conservative critics of his reservations about missile defense systems. But those were policy debates, not questions of qualification.

Tower’s nomination became a media circus because of stories about his personal conduct. Did he abuse alcohol? Was he guilty of sexual assault or harassment? Tower was twice divorced, and both marriages ended with rumors of infidelity. His own Senate staffers admitted that he drank heavily when his first marriage ended and regularly used alcohol in social settings with colleagues and donors. Neither infidelity nor inebriation were unusual on Capitol Hill, and one of Tower’s fellow senators, in an earlier and less politically correct time, told a reporter that “he would never trust a man who didn’t drink a little and chase a little.”

The problem with Tower’s nomination involved the evaluation of claims that his use of alcohol and behavior toward women went beyond the limits (admittedly vague) of what would be acceptable for a cabinet officer. This debate took place in public and sometimes involved wild accounts of Tower’s inappropriate behavior. Some of them were false, but the steady stream of stories made the public suspicious about the nominee.

And there was partisanship. Democratic senators, who held the majority when Bush was elected, probably enjoyed having an issue that distracted the president in his early weeks in office and filled the media with salacious accusations about a member of the new administration.

In the normal course of confirmation controversies, a nominee like Tower would be withdrawn to save the candidate and the president from unpleasant disclosures and distractions. But the Tower controversy was a matter of loyalty. Not the loyalty of a nominee to a president, but the loyalty of a president to a friend. On several occasions, Tower volunteered to step aside and end the controversy, but Bush would not allow it and forced the Senate to take a vote. Tower lost and became the 9th cabinet nominee in U.S. history to be rejected in a floor vote, and the only one ever rejected for a newly elected president.

In the months ahead, a floor vote and a cabinet nomination rejection could happen again. If it does, the rejection is more likely to involve questions about personal conduct than job qualification.

If the nominations of Matt Gaetz and/or Pete Hegseth are rejected by the Senate, it will suggest that the Tower nomination set a new standard and was not an aberration.

But if Trump’s controversial nominees are approved on the Senate floor, or in recess appointments that circumvent Senate responsibility, it will mean that we no longer care all that much about the personal conduct of candidates for high office and simultaneously accept cabinet officers with little or no qualification for the office they hold. The Tower controversy won’t be a precedent, it will be an anachronism.

Ted Olson's lessons for the Trump era

Barbara Perry recalls getting to know the former solicitor general

I read with sadness about the passing of Ted Olson, former solicitor general under President George W. Bush. How appropriate that the news broke on the same day that President Joe Biden welcomed Donald Trump, the once and future chief executive, back to the White House. Although the 45th president would not grant the 46th president-elect the same curtesy of meeting at the Executive Mansion after the 2020 election, because Trump denied that he had lost, Biden followed the norm of power’s smooth transition in our democratic-republic.

Olson would have been pleased, for he embodied the same traditional values of statesmanship and devotion to the rule of law as Biden has reflected through his half century in American politics and government.

Olson presided over the legal maneuverings in what had, before 2020, been the most contentious U.S. presidential election, that of Bush v. Gore in 2000, and won his arguments for George W. Bush at the U.S. Supreme Court. He talked at length about his strategy in the Miller Center’s 2012 oral history with him, and I summarized the lessons of his masterful oral arguments before the high court for TIME in 2020.

I had the honor of getting to know Olson through my University of Virginia mentor, Professor Henry Abraham, and was always impressed by his gentlemanly demeanor, wry humor, and superb oral argument style, highlighted by a basso profundo voice that was right out of central casting.

But what I will remember most about him was his open-mindedness to collaborate with his opponent in Bush v. Gore, fellow lawyer David Boise, in their support for marriage equality. Not only was Olson willing to embrace a former adversary, he departed from many of those in his conservative circle to evolve on the question of whether the Constitution protects marriage of same-gender couples.

In this age of division, partisanship, violence, culture wars, and vulgarity in our politics, the lessons of both law and civility, exemplified by Olson’s public service, should resonate long beyond the laudatory eulogies he so richly deserves.

The House district results that tell the presidential story

In Sabato's Crystal Ball, Kyle Kondik writes that Trump's gains among Latino voters jump off the screen

After President-elect Trump’s victory and the Republican capture of the Senate last week, the House of Representatives majority remains uncalled by most news organizations, although the writing is on the wall.

Our own best guess is that the House GOP majority will be something like 220-222 seats at full strength—although the House will not be at full strength for long, for reasons we’ll get into throughout this piece.

On the Sunday before the election, I wrote an op-ed in the New York Times exploring some key House districts that I thought would tell us something about both the race for the House and the race for the presidency. I’m going to use those same districts (and some others) to identify notable highlights from the results.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEPost-election analysis

UVA experts discuss the election results

The end of Florida as a swing state

Miller Center Assistant Professor Cristina Lopez-Gottardi Chao assesses the Hispanic vote in Florida

Based on early reporting, 2024 appears to have brought a decisive end to Florida’s status as a swing state. While Trump won the state in 2020, it was by a tight margin of just over 3 percentage points. This year, the gap is roughly 13 points, 56.2 to 42.9 percent. That’s a decisive shift.

Of course, Florida is home to a large and diverse population that includes Hispanics – specifically Cuban Americans (who make up 41 percent of Florida Latinos) and Venezuelans who tend to lean right, Puerto Ricans (18 percent) who lean left, and a mix of other cohorts (Mexican Americans, 17 percent, and South Americans, 13 percent) whose vote tends to be more divided.

As a whole, Florida’s Hispanic population mirrored the state race, giving Trump 57 percent compared to Harris’ 41 percent. As we sift through exit polling data in the days and weeks to come, we will learn more about how these various subgroups voted and what that may reveal about both state and Latino voting trends going forward.

Recriminations, and deep structures

Miller Center Professor Guian McKee writes that the Democratic base was never going to be enough for Harris to win

Within the Democratic Party, painful analysis and recriminations from Donald Trump’s victory will begin immediately. Should Biden have dropped out sooner? Once he did drop out, should the party have staged some form of competitive selection process? Should Harris have chosen Josh Shapiro as her running mate? Should she have separated herself more clearly from Biden? Should she have gone on Joe Rogan?

These are all reasonable questions, and worth considering (for what it’s worth, I would answer yes to most of them, with some hesitation on the VP selection as I’m not sure Shapiro would have made a difference). They all, however, obscure the basic problem that Trump’s second victory reveals: the Democratic Party has too narrow a base, and that base represents institutions that many Americans believe have failed them.

The coming weeks will provide ample opportunity for detailed analysis of exit polls and returns, but two things seem clear on this morning after the election: First, the education divide and unhappiness about the economy likely drove Harris’s loss; second, those two factors are deeply related.

Democrats including Harris have done very well among the college educated, and increasingly badly among those with less than a college education. The problem is that there simply aren’t enough college-educated Americans to win elections on a consistent basis, as they constitute roughly 45 percent of the country. Add in a gender divide that bleeds out a percentage of male college-educated voters, and the problem gets worse.

To win, Democrats need to find ways appeal to voters outside this base.

The second aspect--the economy and specifically the legacy of the high inflation of the post-Covid period--shows a related problem. College-educated Americans are broadly more affluent, and hence were more insulated from the harms of inflation.

In contrast, less educated and less affluent Americans felt inflation every day, every month. The seeming indifference of the Biden administration to the problem (even if they were correct in blaming inflation on global trends, and even if there was little the president could do in the short term) created the impression of institutional failure and lack of concern for everyday working people.

This sense of policy failure built on the legacies of other failures that had little effect on the college educated: Covid lockdowns (which gave Trump, somehow, a pass on his own Covid failures), the financial crisis of 2008-2009, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, deindustrialization. The list goes on. Against an insurgent, blow-it-all-up candidate, Harris and the Democrats looked like the candidate and party of the failed institutions.

This was a high hill to climb, and one that going on Joe Rogan might not have solved. It will remain the core challenge for future Democratic candidates.

What is a president, anyway?

Miller Center Professor Russell Riley writes in the Washington Post that it takes vision

The Oval Office sits at the apex of an enormous idea industry, with hundreds of initiatives flowing into a president every week, each the brainchild of political entrepreneurs sure that if they could only get presidential buy-in, they could fix the government, or whip inflation, or lasso China.

So, a central part of the president’s job is to prioritize — to recognize limits and thus to refuse to spend time promoting every notion that has merit. Most often this role is exercised in the negative: “No, we can’t do that.”

But there are also rare moments when the reverse happens: Presidents are confronted by seemingly impossible problems, and — based on their unique vision of the situation and their own willingness to risk political capital — say, “We can do this. We must do this.”

What is a president, anyway?

Melody Barnes, executive director of the Karsh Institute of Democracy, says it's lonely at the top

George Tames’ famous photograph of President John F. Kennedy alone in the Oval Office, palms pressed on his desk, deep in thought, was taken just three weeks after his inauguration in 1961. It captures the weight of what begins as a steady stream and quickly becomes an open fire hose of challenging, sometimes life-and-death, questions that can be answered only by the president. What should be the terms for reconciliation now that the Civil War is over? Should we send more troops into Vietnam or bring them home? Should I pardon Richard M. Nixon or not? Should there be comprehensive health-care reform or something smaller? How do we protect millions of people from a previously unknown virus now killing thousands of people daily? Rarely are the answers obvious or easy.

The size of the nation, the needs of its people and our relationships around the globe require members of the president’s Cabinet and the executive branch staff to make hundreds of decisions that will never touch the president’s desk. Only the most consequential and complex — including those upon which senior aides, Cabinet secretaries and agency heads are deadlocked — get to the president.

The final 2024 ratings

Sabato's Crystal Ball still hasn't found their crystal ball

We mentioned a few weeks ago that we misplaced our Crystal Ball. As an update, we regret to say that we still have not found it. So no final ratings this year. Have fun on Tuesday!

OK, fine, we’ll give it a try.

We are not going to try to concoct some grand theory as to why one candidate may be favored in this election. We’ve tried them all out, and we don’t find anything that is convincing—if we did, we would have said so by now. We will leave it to the Wednesday morning quarterbacks—or is it Thursday or Friday?—to tell us how clear it was that Kamala Harris or Donald Trump would win. These things seem obvious in hindsight, but the outcome sure doesn’t seem obvious to us now.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEHow historically unusual is this election?

Miller Center Director William Antholis explains that the plot twists in this election have happened before

Many Wahoos will make their first presidential choices Tuesday. And they’ll be choosing between two candidates who landed at the top of the ticket through unusual paths. UVA Today asked William Antholis, director and CEO of the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs, to put the circumstances of this election into perspective. Antholis, a 1986 UVA graduate, previously served as managing director at The Brookings Institution and held positions at the White House National Security Council and State Department.

Q. This election will be the first time many in our community cast a ballot. What should they know about this election and how unique it is to U.S. history?

A. As wild as this election has seemed, both of those plot twists have happened before. And they seem to favor former President Trump.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEThe shifting Hispanic vote

Miller Center Assistant Professor Cristina Lopez-Gottardi Chao scrutinizes the effort to court Latinos

With just days to go before the election, there continues to be confusion and uncertainty about the fate of the Hispanic vote. Expected to make up nearly 15 percent of the electorate, Latino voters have increased by roughly 4 million since 2020. Long considered an advantage for the Democrats, Hispanic voting patterns appear to be shifting, with gains expected for the Republican party. This is making Hispanics a bit of a wildcard in this year’s election. And while this shift is still in motion and remains unsettled, there are some who argue that it may be rooted in class and generational changes.

In a late September NBC/CNBC/Telemundo survey of 1,000 registered Hispanic voters, Vice President Kamala Harris leads former President Donald Trump by 54% to 40%, marking the lowest Democratic lead amongst Latinos in the last four elections. At a similar point in 2020, Biden’s margin was 36 points ahead. That’s a significant and meaningful contrast that warrants inquiry and should raise concern for the Democratic Party.

In the 2020 book The Hispanic Republican, Gerardo Cadava examined the evolution of the Hispanic vote, and more specifically, the increasing cohort of Republican Latino voters. He argues that the Latino vote is more complex than its ethnicity reveals and that essentially there are no universal truths about this demographic, rather, growing complexity and nuance. In a 2020 interview, Cadava said Hispanics represent, “…a real diversity of political beliefs, and we need to acknowledge that Latinos are fully human, complicated political actors, rather than just kind of pawns that are easily poached or persuaded, just because a politician talks to them.”

In a September Politico article by Ryan Lizza, Mike Madrid adds that “the biggest problem with courting Latinos might be that politicians think of them strictly as an ethnic group in the first place.” He goes on to say that “minority voters are voting much more along economic class lines than they are as a race and ethnic voter….” These trends may be due to the fact that inflation, the economy, jobs, and cost of living rank as top issues for Hispanics. And recent polling reveals Trump is favored over Harris by 9 points to handle the economy. Add to that, April 2024 polling which found that 63% of Hispanics disapproved of Biden’s performance as president, sentiments that will likely have some carry over effect on Harris’ candidacy.

Another factor adding to the uncertain fate of the Hispanic vote this year, is historically lower turnout rates. As I wrote in 2018, Latinos tend to vote in significantly smaller numbers than the national average. In 2016, Hispanic turnout was just 47%, in 2020 it rose to 54%, but still well below turnout for African-Americans at 63% and non-Hispanic whites at 71%. With such a close race predicted this year, Hispanic turnout rates could have meaningful implications in a number of key states that include Texas, Virginia, New York, Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, Florida, and others.

In the few days left before the election, both parties should be sure to continue their efforts to court this important demographic and encourage their participation at the ballot box. And messaging matters. If Madrid and Cadava are right, outreach that appeals less to ethnicity and more to basic “bread and butter” economic policies will prove most productive in these final days.

The presidential transition

Miller Center resources to support best practices for presidential transitions

The Miller Center is a national leader in understanding and providing expert guidance on presidential transitions.

That includes three books published by UVA Press (Year Zero; The Peaceful Transfer of Power; Crucible) and dozens of essays as part of the First Year Project.

Our landing page on presidential transitions is a one-stop destination for resources on presidential transitions, including helping to understand turbulent presidential transitions.

THE PRESIDENTIAL TRANSITIONWhen will we know?

Miller Center Director Bill Antholis and UVA student Laura Howard chart the path between Election Day and final certification

“When will we know the election outcome?”

Americans are right to wonder, and even worry, about when we will know who our next president will be. The 2020 election went into overtime, and then – on January 6th, the day Congress was to certify the results – it descended into an insurrection.

To help explain the steps between voting and final certification, we have prepared two charts designed by Creative Director David Courtney that update charts we prepared in 2020 in anticipation of a contested election.

In an uncontested election, we typically “know” the outcome when news organizations project the winner on election night. These news outlets wait until after the polls close, but often make the projection before all the votes have been counted. Projections are based on votes counted, and assessments of how other yet-to-be-counted precincts have voted in the past.

In very close elections, however, news organizations wait until all ballots have been counted. The first chart focuses on the biggest immediate Election Day speedbump to the counting: the tabulation of early in-person votes, as well as of mail-in and absentee ballots. Even in close elections, news outlets may still project a winner, but only if they think a candidate’s projected lead surpasses the number of uncounted absentee or mail-in ballots.

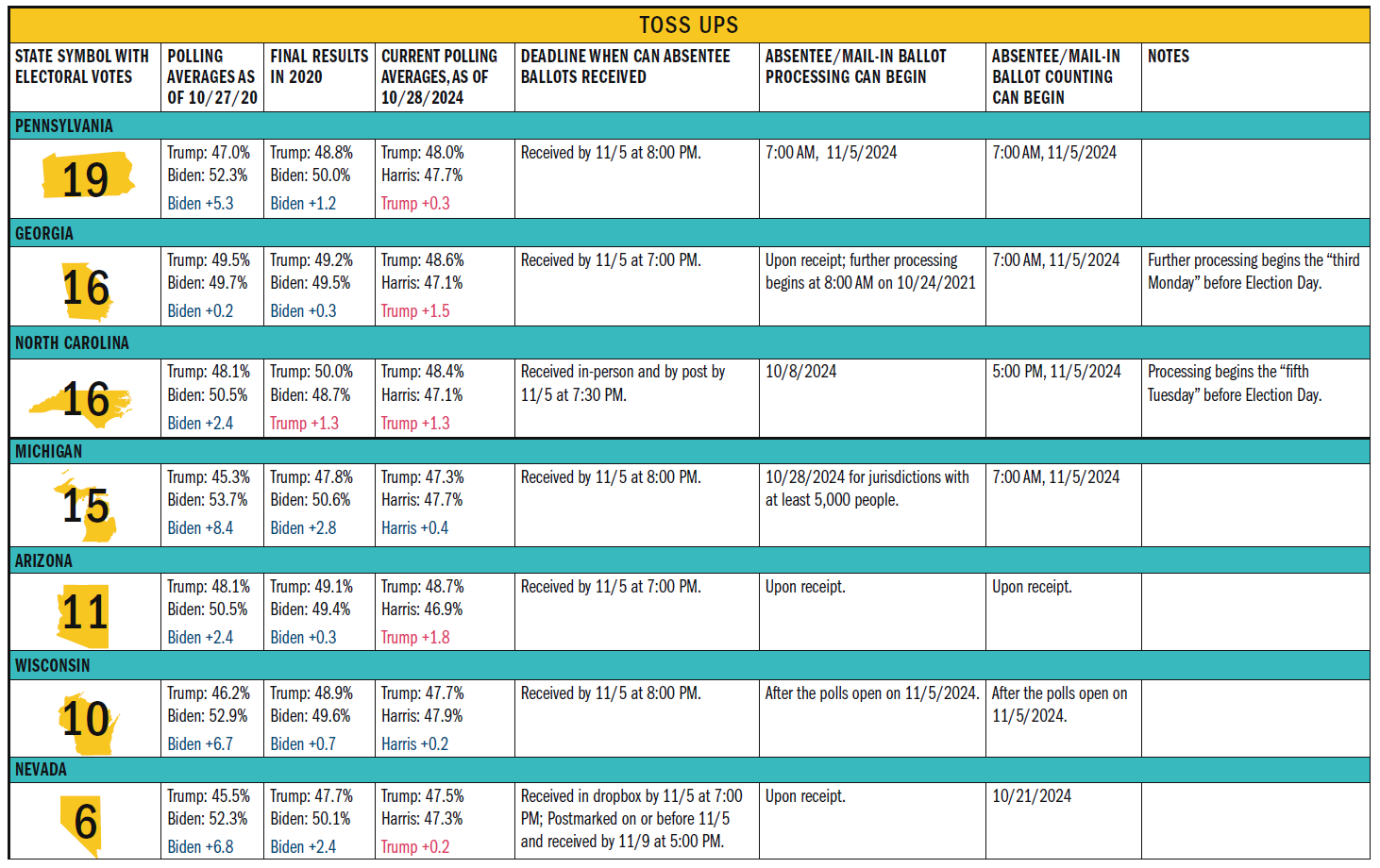

In 2020, for that reason, most news organizations were slow to project the outcome of the election in seven swing states: Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina, Michigan, Arizona, Wisconsin, and Nevada.

This chart shows when these states can begin to process and count absentee and mail-in ballots. Ballot processing can take some time. It typically involves opening envelopes, checking voter signatures and other data, flattening and scanning ballots, and safely storing those ballots.

After the initial counting, candidates and/or private citizens can delay a state’s certification processes by asking for a recount. In fact, most states have automatic re-count thresholds. The swing states listed in the chart all do this differently.

- Arizona mandates an automatic recount when the margin between the candidates is less than or equal to 0.5% of total votes.

- Georgia outlines specifications for superintendents to file requests and allows candidates to do so when the results are within 0.5% of total votes.

- Michigan allows candidates who suspect fraud or mistakes to call for recounts in that office.

- Pennsylvania empowers any three qualified electors to request a recount.

- Nevada allows candidates and voters to request recounts.

- North Carolina allows candidates to do so when the winners’ votes are not 1% more than total votes.

- Wisconsin allows any candidate to request a recount.

Once state election officials tabulate vote totals, senior state officials (typically the Governor or Secretary of State) formally certify the vote and submit the state’s electoral votes. The “Metro Map” tracks the progress of certification after election results are tabulated, showing different routes from Election Day to Congressional certification.

In elections without considerable controversy, this happens with little fanfare.

You might think about that as the express train from Election Day to Congressional certification. The “Green Line” is the express train if there are no challenges to the vote counts.

The “Gold”, “Red”, and “Blue” Lines trace the process if challenges emerge, either in the courts, by campaigns and private citizens, or in Congress.

The Gold Line shows what happens when election results are challenged. The Gold Line on the left-hand side of the graphic shows what happens when challenges are brought to the courts by campaigns or private citizens. That has happened throughout American history. Presidential elections in 1876, 2000, and 2020 famously involved local and state courts facing challenges about election results. In 2020, there were 62 legal challenges regarding the conduction of the election. All but one were dismissed by district and superior courts.

When courts affirm a state’s certification, the Blue Line brings the certification back to the Green Line, heading toward Congressional certification.

When lower court decisions are appealed, the Red Line brings cases to higher courts, including possibly to the Supreme Court. In both 2000 and 2020, the Supreme Court ruled on ballot cases, determining how ballots were to be counted by the Electoral College. Once again, the Blue Line brought those decisions back to the Green Line.

The right-hand side of the graphic shows an alternative Gold Line, which kicks in after states have tabulated and certified results. Members of Congress can challenge tabulations and certifications, including after any relevant court challenges have occurred. This is the procedure over which Vice President Pence was presiding on January 6, 2020 when rioters broke into the Capitol.

In 2022, the Electoral Count Act was amended to clarify the limited role of the Vice President, as presiding over the reporting of results. The 2022 Act also increases the requirements for Congressional objections about states’ electoral counts from any single member to requiring 1/5 of voting members of Congress. It also mandated that states appoint their electors on Election Day, and affirmed that Congress must count the votes that courts determined were compliant with state and federal law (as opposed to exercising independent judgement of who should win). If there is a clear winner of the electoral count, Congress is required to certify the results.

If for whatever reason, there is no majority in the Electoral College – for instance, if there is an Electoral College tie or if a state casts its ballots for a third party candidate, denying either of the major parties a majority – then Congress faces a “Contingent Election.” In those circumstances, the House votes by state delegations – with each state getting one vote. That occurred in the elections of 1800 and 1824.

William Antholis is the Director and CEO of the Miller Center.

Laura Howard is a fourth year student at UVA, the director’s intern at the Miller Center, and chair of the UVA Honor Committee.

One week to go, and two contradictory ‘gut’ feelings

Kyle Kondik says Sabato's Crystal Ball is feeling a bit, um, queasy

At roughly the same time in the middle of last week, two skilled election analysts—Nate Silver and Sean Trende—published similar columns arguing that the presidential election remained a coin flip, but that for a variety of reasons Donald Trump might be slightly favored. Silver even referred to his “gut” suggesting a Trump win, although he quickly added that observers shouldn’t trust their gut, or his.

Suggesting that Trump might have a tiny edge is defensible. The polling, although still incredibly close, has gotten a little bit better for Trump over the past several weeks. One of the ways to measure this is through the movements in forecasting models that take polls into account, such as the one Silver publishes at the Silver Bulletin, as well as the different one at his old website, FiveThirtyEight, along with another model published by Decision Desk HQ/The Hill. All of these models showed Kamala Harris with a very slightly better chance to win the election over Trump as of Oct. 1 (her chances of winning were about 55% in all three models back then). These forecasts have now moved to roughly a 55% chance for Trump, as of Tuesday morning.

Now, practically, what’s the difference between a 55% chance for Harris versus a 55% chance for Trump? Hardly any. Both candidates had a decent chance of winning on Oct. 1, and both have a decent chance of winning now. There continues to not be a clear favorite.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEEven if Harris isn't talking about gender, everyone else is

Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless is interviewed by NBC News about the gender gap

In just two weeks, Kamala Harris could make history as America’s first female president. You don’t hear her talk about it much.

“The experience that I am having is one in which it is clear that regardless of someone’s gender, [voters] want to know that their president has a plan to lower costs, that their president has a plan to secure America in the context of our position around the world,” the vice president told NBC News in an interview Tuesday.

But while Harris isn’t talking about it, everyone else is.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEImmigration, disinformation, and violence…in 1880

Miller Center Senior Fellow Robert Strong writes that history is repeating itself

In the 1880 presidential campaign, both candidates — Republican James Garfield and Democrat Winfield Hancock — called for restrictions on Chinese immigration to the United States. Neither supported the complete ban that many westerners wanted.

Just before Americans went to the polls, Democratic newspapers across the country printed a letter, supposedly written and signed by Garfield, that endorsed an open border (or an open ocean) to Chinese immigration. Before anyone learned that the letter was a fake, there was public uproar. In Denver, an angry mob burned down the homes of Chinese immigrants. One was killed.

When the ballots in 1880 were finally counted, Garfield won the popular vote by a narrow margin, a tenth of a percentage point, and found himself in a weak position to do much about immigration or other pressing issues.

Looking back at the post-Civil War era, we could take some comfort in the realization that aspects of our contemporary politics are not new. But if we dig a little deeper, we may be able to learn more about what is constant and what is changing in American politics.

Immigration has been an issue throughout our history. It tends to become more salient when the numbers are high. After the Civil War, the proportion of people in the United States who were born in another country rose to over 14 percent, about the level it has reached in our own time. Though everyone in the United States (except Native Americans) has an immigrant ancestor in their family history, hostility to the newly arrived has long been fodder for demagogues and nativists. It can easily be used to win votes or gin up violence.

Disinformation, like immigration issues, is also nothing new. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson’s supporters spread stories that John Adams was nearing death—a pretty good reason not to vote for him. Almost every election has rumors, allegations, and dirty tricks. We are particularly vulnerable to fake and fraudulent political claims because of our constitutional commitment to free speech and our decision to give extra protection to political discourse. That discourse can be coarse, crude, and full of falsehoods, but we generally trust that citizens and voters will find the facts they need to make good decisions and keep the perennial liars in check.

That said, we may be in a time when the disappearance of information gatekeepers, the speed of dissemination, and the ability of multiple actors to generate convincing evidence supporting false claims has made matters worse. Maybe much worse. Is the Garfield letter a reminder that we have always had disinformation in our politics, or evidence that we used to be amateurs at this game?

And what about violence? There are times when some Americans have unleashed brutal attacks on immigrants, racial minorities, and political opponents. It happened in 1880. But in the long run, these have been tragic chapters in a national story whose central theme has been growth in diversity and expansion of rights.

January 6, 2021 was a reminder that shocking political violence is still possible in America. Will this election cycle close that chapter or keep it open? That may be the most important question about the 2024 presidential election.

What we don’t talk about when we talk about Kamala Harris

Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless explains in Vox why Harris, unlike Hillary Clinton, is not running an identity campaign

Eight years ago, when Hillary Clinton seemed poised to be elected the first female president of the United States, it sometimes seemed as though the candidate and the media couldn’t talk about it enough.

“I think it would be a great moment for our country,” Clinton told 60 Minutes about the possibility of becoming the first woman in the Oval Office. “Every little boy and every little girl should be given the chance to go as far as his or her hard work and talent might take them.”

On the trail, she underscored the possibility that she would end America’s long tradition of only electing men for president. “Clearly, I’m not asking people to vote for me simply because I’m a woman. I’m asking people to vote for me on the merits,” Clinton said at one event in 2015. “I think one of the merits is I am a woman, and I can bring those views and perspectives to the White House.”

READ THE FULL ARTICLEHas anybody seen our crystal ball anywhere?

Kyle Kondik says the Center for Politics is kind of flummoxed

With three weeks to go before the election, we have an unfortunate announcement to make: Our crystal ball is missing.

We don’t know what happened. Maybe one of us left it at the office, which is now under construction as part of a major renovation and expansion project. Maybe the ghost of Mr. Jefferson whisked it away. Maybe we’re… ummm… making excuses. Anyway, we just can’t figure it out!

Hopefully we’ll get it back sometime over the next three weeks, because we’re going to need it. Some bit of mystical forecasting magic may be required to come up with a halfway-decent forecast of this election, because those looking for clear signs about which way this election is going to go, including us, are likely to be disappointed.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEThe problem with Trump's hard-line on tariffs

Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless tells Bloomberg Radio why she sees a downside to former President Donald Trump's economic proposals

Stop obsessing over horse race polls, UVA political analyst says

Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless offers tips to avoid "polling whiplash"

Election Day is coming up, with just weeks separating Americans from the final results. Many are obsessively looking to polls, hoping for a hint as to what the future holds.

However, Chair of University of Virginia’s Politics Department Jennifer Lawless said now is this time to avoid obsession over the numbers and ‘polling whiplash.’

“A lot of people are getting polling whiplash right now because they’re looking at all of the different polls, and they’re looking at who’s up and looking at who’s down," Lawless said.

WATCH THE VIDEOWhy visit those states? How the Electoral College influences campaigns

Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless and the Center for Politics' Kyle Kondik offer a primer

Thanks to a U.S. Constitution quirk, the Electoral College and not the nation’s popular vote decides who will be the country’s top executive. Most Americans would like that changed.

When voters cast ballots, they’re actually voting to send a slate of electors representing their preferred candidate to the Electoral College. Each state is assigned a number of electors equal to the sum of its U.S. senators (two) and members of the U.S. House of Representatives (which varies by population).

The winner of the vote in the Electoral College takes the presidency, even if the other candidate wins the national popular vote.

READ THE FULL ARTICLECan Kamala Harris overcome the VP curse?

Barbara Perry writes in Newsweek that vice presidents get a bum rap and sometimes the bum's rush

Vice presidents get a bum rap and sometimes the bum's rush. Thomas Marshall, Woodrow Wilson's VP, quipped, "Once there were two brothers. One ran away to sea; the other was elected vice president of the United States. And nothing was heard of either of them again." Kidding aside, nine of our 45 chief executives have died or resigned, so the odds are 20 percent that a vice president could become president.

For the first time in nearly a quarter-century, we have an incumbent vice president, Kamala Harris, running for the presidency. Not since Al Gore narrowly lost to George W. Bush in 2000 has the sitting vice president vied for the Oval Office. Second place has been the most frequent finish for those second in command when they have run for chief executive in the modern era. Does vice-presidential service curse candidates?

After Vice President Martin Van Buren's 1836 victory, no incumbent VP garnered the presidency until George H. W. Bush did so in 1988.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEWhy women will determine the next American president

Miller Center Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless discusses the importance of female voter turnout in a Bloomberg podcast

Defining ‘close’ in the context of the 2024 election

Kyle Kondik writes that most people expect the presidential race to be close, but what does that actually mean?

You have heard it ad nauseam from us and many others who follow elections: This presidential election is close. The polling averages in the swing states are very close to tied, with Kamala Harris generally ahead by a hair in the northern battlegrounds and Nevada and Donald Trump generally ahead by a hair in the Sun Belt battlegrounds.

What would constitute a surprise in 2024 would not be either Harris or Trump winning. Instead, the surprise would be if the election is not close and clearly breaks to one candidate or the other.

But that also begs a question—what do we mean by “close?” Is there a specific benchmark that makes an election close, or not close? It’s clear that the race is close in polling—whether the election actually is close will be a determination we will not be able to make until the dust settles.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEScandals just aren't what they used to be

Miller Center Senior Fellow Robert Strong writes that the country has moved a long way from Gary Hart to Stormy Daniels

Presidential elections are not what they used to be. We see evidence of this all the time, but here’s a brief reminder that not that long ago a minor scandal in the personal life of a presidential candidate could end a political career.

Early in the 1988 presidential campaign, there were rumors of marital infidelity concerning the leading Democrat, Senator Gary Hart, who was seeking his party’s nomination. Hart denied the rumors and challenged reporters to follow him around to see if they could find any evidence of alleged affairs. Accordingly, some journalists—practicing the “highest” standards of their profession—hid in the bushes outside Hart’s townhouse. On one evening they saw a young woman arrive and leave. Sometime later a photographer in Florida took pictures of Hart on the back of a yacht and on a pier with the same woman, Donna Rice, sitting on his lap. In one photograph, the name of the yacht was clearly visible: “Monkey Business.”

Hart’s campaign and chances of becoming president of the United States were over. That was almost 40 years ago. A lot has changed.

Donald Trump has been recorded on tape saying that celebrities can grab, grope, and kiss women with impunity. Twenty-six women have accused him of sexual misconduct. Trump has denied all the allegations and repeatedly criticized E. Jean Carroll for her published account of what she said was a Trump sexual assault against her in the 1990s. When Carroll sued, juries heard evidence and found that Trump, more likely than not, was guilty of the assault. One judge called it a rape. Trump was also found guilty of defamation and ordered to pay millions in damages.

In another New York courtroom—this time a criminal trial involving false business records—the prosecution made a case that Trump and his friends paid a porn star, Stormy Daniels, and a Playboy model to stay silent about their affairs with Trump, keeping their stories out of circulation during the 2016 presidential campaign. The hush money payments to Daniels were made by Trump’s “fixer,” Michael Cohen, who was later repaid with funds fraudulently reported as legal fees. Trump was found guilty of 34 felony charges by a unanimous jury.

Readers of this blog don’t need a primer on the catalogue of Trump allegations and litigations related to sexual misconduct. I summarize the familiar rap sheet in order to present the sharpest possible contrast to Gary Hart’s "Monkey Business" photograph.

The standards of personal conduct that get applied to presidents and presidential candidates have not just declined in the last 35 years. They have nearly disappeared.

How has this happened? Clearly the public attitude about the personal behavior of our political leaders has evolved. That evolution was evident in the 1990s, when Bill Clinton’s presidential approval numbers stayed steady, or rose, during his impeachment for lying under oath about his affair with Monica Lewinsky. Clinton remained a popular president but paid a price in reputation and legacy with many Americans. Has Trump paid a similar price?

Lots of people don’t like Trump’s style and character, but some of them are willing to vote for him despite his manifest flaws. Will 2024, in the final analysis, be seen as a traditional policy election or a more unusual character-dominant campaign? We don’t know, but it is perfectly clear that there has been a sea change in the way we think about the personal behavior of public figures. Like the "Monkey Business," we are in uncharted waters.

Tim Walz 'like a deer in the headlights'—Analysts on who won VP debate

Miller Center Professor Barbara Perry assesses the vice presidential debate

The vice presidential candidates faced off in New York on Tuesday night to debate their platforms and defend their respective running mates.

With polls indicating one of the tightest elections in history, and several major crises facing the country and the world in the days leading up to the debate, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, the Democratic Party's nominee for vice president and his Republican counterpart Sen. JD Vance clashed over foreign policy, economics, border security, abortion and the peaceful transfer of power.

Newsweek heard from analysts, experts in debate, and professors of political science, who have broken down which points they think landed, which points did not, and overall, who they believe walked away on top.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEStrikes and presidential elections

60 years ago, a major strike threatened to upend a presidental campaign, writes Miller Center Professor Guian McKee

On the morning of October 5, 1964, United Automobile Workers President Walter Reuther informed President Johnson that his union had agreed to a new national contract with General Motors. The agreement marked the first step towards resolving a strike that had idled 260,000 workers at the nation’s largest automaker just weeks before the 1964 presidential election.

Commenting on his approach to the situation, Reuther remarked to the president that “I didn’t want to bother you, because I didn’t want anybody to, when they raised every time that I talked to you and I said no, and I didn’t want to get you involved.” Johnson responded simply: “Good.”

Today, the U.S. is faced with a similar confluence of labor conflict and politics.

Early in the morning of October 1, 46,000 members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) went on strike at critical ports on the East and Gulf Coasts. The union’s dispute with the United States Maritime Alliance focuses on wages, which have been undercut in recent years by inflation, and on port automation, which has the potential to reduce ILA jobs.

Taking place just five weeks before the presidential election, the port workers strike creates dilemmas for President Joe Biden and for both presidential candidates. Although preemptive stockpiling of goods by companies means that a short strike will have relatively little impact, a strike lasting more than a few weeks could create shortages and raise prices. Supplies of perishable fruits and vegetables could be affected even sooner.

In the event of a longer strike, Biden will have to decide whether to invoke the Taft-Hartley Act and force the workers back on the job as negotiations continue. The Harris and Trump campaigns, meanwhile, will have to balance supporting workers and courting union voters with the potential rising anger of consumers seeking crucial staples as well as holiday items.

Hope for a resolution, however, might be found in the 1964 strike. In that case, the president (and his opponent) avoided deep involvement, despite serious economic stakes, and the parties involved reached a settlement prior to the election.

The 1964 strike at GM came as something of a surprise, as many observers believed that UAW agreements with Ford and Chrysler, reached during the previous month, would provide a model for a similar deal with GM.

Like the striking dockworkers today, UAW members in 1964 had grown concerned over a series of non-wage issues. These included the ability of the company to mandate overtime for workers, as well as the right of union committeemen to work full-time on grievances brought by other members. A further complication resulted from union leadership’s decision to link a national settlement with the resolution of 130 specific grievances raised by union locals at plants around the country. As a result, a national contract alone would not end the strike.

As the strike began on September 25, Reuther called on GM to “meet the minimum standards of human decency.” On October 5, he observed to Johnson that “our fellows, who have been working 13 hours a day, excessive overtime, month after month after month, they can’t get any time off, and they’re just in a state of rebellion! And when we proposed arbitration and the company turned it down, you just couldn’t hold these guys.”

Louis G. Seaton, the GM vice president heading the negotiations, in turn accused Reuther and the union of using the working conditions claim as “a cover for other things” – presumably, increased wage and benefit demands.

With the highly anticipated new model year just beginning, GM estimated that it would run out of new 1965 models of its cars within two weeks. Older 1964 models would be gone in 18 to 20 days.

The resulting risk of consumer frustration formed just the first part of the delicate political task facing Johnson. Union members and organizational strength represented the backbone of the Democratic Party. Faced with potential voter defections in the South because of his support for civil rights legislation, Johnson could not afford to alienate the UAW or unions generally.

Yet at the same time, much of LBJ’s wider electoral strategy had been based on the Kennedy-Johnson record of sustaining economic prosperity without inflation. “Wage-Price Guidelines” – a form of suggested but not binding controls – constituted a key part of the administration’s economic policy. With the auto industry a huge part of the U.S. economy in 1964, any settlement that led GM to raise prices on cars risked upsetting this balance and kicking off inflation. As The New York Times noted the day after the strike began, “A prolonged strike [at GM] could damage the United States economy and President Johnson's election prospects.”

Nonetheless, as the call with Reuther indicates, Johnson avoided direct intervention. Instead, the Department of Labor deployed federal mediators to facilitate the negotiations, which LBJ monitored behind the scenes. On October 5, GM and the union reached a settlement on the national contract, and, after a few additional weeks of complex negotiations over plant-level problems, resolved the remaining local issues.

In the October 5 call, Johnson and Reuther discussed the political implications:

President Johnson: That’s good. Well, I’m mighty glad it’s over with.

Reuther: And we couldn’t, you see, if we let the guys down, Mr. President, then your best friends and your best troops would have been demoralized just when we’re trying to get them marching on this other thing.

President Johnson: OK. Well, we sure need to get marching.

With the strike settled and the threat of car shortages defused, Johnson went on to a landslide victory.

The resolution of the 2024 strike, much less its political consequences, remains to be determined. Even in the early hours of the strike, the two sides have made counteroffers that brought them closer together after months of stalemate – suggesting that, perhaps, a repeat of the 1964 labor resolution might be at hand, even if an ensuing landslide win for either presidential candidate seems implausible.

Incumbents stay strong in South America

Christopher Carter, from the Karsh Institute’s John L. Nau III History & Principles of Democracy Lab, looks at trends in South America

In 2024, six Latin American countries—El Salvador, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Venezuela, and Uruguay—voted for, or will vote for, presidents in general elections. One of the most interesting insights from these elections has been the strong performance of incumbents and their parties.

In Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum, the handpicked successor of the incumbent (Andrés Manuel López Obrador), who is term-limited, won with the largest percentage of the vote of any presidential candidate in Mexico’s history. And in El Salvador, Nayib Bukele was reelected with an eye-popping 85% of the vote. Rarely do we see such overwhelming support for any candidate in free and fair elections. While not universal—Panama’s incumbent party performed poorly and Uruguay’s incumbent party is currently trailing in the polls—the anti-incumbent sentiment we have seen in many other parts of the world seems weaker in Latin America’s 2024 elections.

The elections also reveal, however, the deep personalism and lack of institutionalized parties that lie at the heart of many Latin American democracies. Political parties in Mexico and El Salvador seem to primarily be vehicles of the incumbent presidents. There is skepticism about how much López Obrador will meaningfully step away from Mexican politics, for example. In Panama, the ex-president, Ricardo Martinelli, who is sequestered in the Nicaraguan embassy in Panama, played a crucial role in getting the new president, José Raúl Molino, elected. Many have even called Molino a “proxy” for Martinelli. Whether these political figures institutionalize their personal support into a lasting party organization remains to be seen, which to date has been uncommon and continues to shape the nature of those parties. (but has heretofore been uncommon).

Crime, the economy, and corruption are most important to voters (especially in Mexico, El Salvador, and Panama). Notably, voters seem willing to accept ceding certain rights in exchange for government action on these issues. The incumbent president in Mexico has been accused, for example, of eroding checks and balances to implement anti-poverty, redistribution programs. Yet, he maintains high approval rates—and his party won overwhelming support in the presidential election. Likewise, voters in El Salvador seem to have mostly embraced Bukele’s crackdown against organized crime, even though there exist many charges of due process violations.

Lessons from the late 19th century

Miller Center Senior Fellow Robert Strong notes that extremely close presidential elections are the norm, not the exception

The last time a president defeated for reelection came back to win the White House was 1892. Grover Cleveland, the 44th president, became the 46th—the only president to hold two nonconsecutive terms. That’s the trick that Donald Trump is trying to repeat this year.

If we look beyond Grover Cleveland to politics in the second half of the 19th century, are there any insights from that era that might help us understand our own political times? Maybe. Here are a few things to consider:

- In the 20 years between the presidencies of Ulysses S. Grant and William McKinley, neither major political party was dominant. Only one presidential candidate from 1876 to 1892 won 50 percent or more of the popular vote: Samuel Tilden, the loser in the controversial 1876 election, did get 50.1 percent, but ultimately lost in the Electoral College.

- Several presidential elections at the end of the 19th century were extremely close. Cleveland won the popular vote in 1884 by less than 1 percent; he won it again in 1888 by a similar margin but lost to Benjamin Harrison in the Electoral College. James Garfield in 1880 won by roughly one-tenth of one percent.

- Twice in this century the winner in the Electoral College lost the popular vote: Bush in 2000, Trump in 2016. There were two similar results in the second half of the 19th century: Tilden and Cleveland after winning the popular vote in 1876 and 1888 each lost in the Electoral College.

- Of course, victory in the Electoral College in the second half of the 19th century was a moving target. The official tally needed to win the presidency changed 14 times between 1850 and 1900 as new states were admitted to the Union.

- Relatively weak presidents (in terms of popular support) at the end of the 19th century were further weakened by the absence of unified government (a single party in control of the House, Senate, and White House). Garfield (and his successor, Chester A. Arthur), Harrison, and Cleveland each had two years of unified government. In the remaining 14 years between Grant and McKinley, the nation had divided government.

- Divided government is common in American politics today. Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden came into office with unified governments and lost the House of Representatives two years later. Republicans lost their majority in the Senate during George W. Bush’s first year in office. The last president of the United States to have four years of unified government was Jimmy Carter.

The end of the 19th century and the beginning of this one are both characterized by closely divided political parties and the absence of decisive elections (political scientists call them “critical” elections) that change the nation in large and long-lasting ways. Those elections are rare, and periods of highly competitive campaigns, like the one we are in today, may be closer to the norm in American politics.

Avoid polling whiplash: 5 things to watch when you’re watching the polls

UVA political science professors Jennifer Lawless and Paul Freedman put all the conflicting polls in context

If you’re obsessed with the polls (like we are), you might be having a hard time keeping track of who is up, who is down, and how the dynamics of the presidential race keep changing. You also might be wondering how to reconcile polls that show different results, even when they’re conducted by the same pollster or on the same day. There’s been lots of attention, for example, to The New York Times-Siena poll that showed Vice President Kamala Harris up by four points in Pennsylvania last week against the backdrop of a tied race nationally. Similarly, a series of polls out this week from the same source show former President Donald Trump up across the sunbelt, despite earlier reports of Harris gaining ground in Arizona, North Carolina, and Georgia.

As poll-watchers risk whiplash and struggle to read the tea leaves of every one-point post-convention/post-debate/post-assassination attempt fluctuation, we risk missing the forest for the (many, many) trees. The race itself is historically close, and has changed relatively little since Harris became the nominee just two long months ago.

Of course, amid an “historically close” race, “relatively little” can mean everything. But it’s still important not to overinterpret shifts in the polls. As we continue to obsess over the torrent of polling data throughout the next six weeks, here are five principles to keep in mind:

Pay attention to the pollster. Not all polls are created equal. Some have better track records; some have better samples; some are better than others when it comes to explaining who they polled and how they did it. If you’re interested in various pollsters’ track records and reputations, ABC News' FiveThirtyEight offers pollster ratings. Scores are based on the historical record and methodological transparency of each polling firm.

Pay attention to when the poll was conducted and who the sample includes. Registered voters, for example, are less likely to turn out on Election Day than “likely voters.” It’s tricky to measure who a “likely voter” is, and different survey organizations do this differently (and almost never explain how). As a general rule, though, surveys of likely voters will have more predictive power than surveys of registered voters.

Pay attention to margin of sampling error. A national poll of 1,000 respondents has a margin of error of about 3 percentage points. This means that if a candidate is polling at 48%, that person’s support could be as low as 45% or as high as 51%. The smaller the sample size, the larger the margin of error. A state poll of 700 people, for example – as in this week’s Times-Siena poll – typically has a margin of error of about 3.7 points. Importantly, these margins of error are estimated for the entire sample. Once you break down the results by party or gender or race, the margin of error increases. In a state poll of 700, if women comprise half the sample, then any analyses restricted just to women carry a margin of error of more than 5 points. Notice that most of these margins are significantly larger than the 1 to 3 point advantage that Harris or Trump enjoys in the battleground states. And if the margin of error is greater than the spread separating the candidates, the result is a statistical tie.

Remember that the margin of sampling error isn’t the only source of error in a poll. It’s the one we focus on because it’s relatively easy to quantify (it’s based on a mathematical formula). But beyond this kind of sampling error – which is random – we must also be concerned about systematic sources of error, such as an unrepresentative sample, differential response rates among politically relevant groups, unclear or biased question wording, or implications of question order. Most high-quality pollsters release the exact questions they asked and the order in which they asked them. Click on those links when you read poll results so that you’re fully informed about the entire poll, not just the head-to-head questions most news outlets highlight.

Don’t pay too much attention to a single poll, particularly if it stands out from the crowd. There’s no way to tell if an outlier is right until more data come in. Instead, take advantage of polling aggregators, like The New York Times or FiveThirtyEight. But keep in mind that, like polls themselves, not all aggregators are created equal. RealClearPolitics, for example, reports a simple average of polls, treating every poll the same. Other aggregators give more weight to pollsters with a better track record, to polls with larger samples, or to those fielded more recently.

At the end of the day, we would all rather our favored candidate be up than down - even within the margin of error. And we’re going to take solace in the polls that work for us and try to debunk those that work against us. Such impulses are understandable. But obsessing over and extrapolating too much from the constant flow of new polls – beyond the conclusion that this is in fact a very close race – is probably not time well spent, and not worth the whiplash.

Okay, we’re going back to obsessing about the polls now.

'Is she electable, though?' Gender bias in the media

Senior Fellow Jennifer Lawless discussed how the media covers female candidates on a panel at the Shorenstein Center

The wisdom of appointing officials from the opposing party

Miller Center Director of Presidential Studies Marc Selverstone recounts the history of this strategic political move

Discussions about how a president-elect might unify the country after a contentious campaign have often centered around the appointment of cabinet or staff officials from the opposing party. Examples of this dynamic are legion and include several cases from the Barack Obama and George W. Bush administrations, as my colleague Barbara Perry has observed (“Foxes in the Chicken House”).

John F. Kennedy made several such appointments as well, including to the high-profile positions of secretary of the treasury (C. Douglas Dillon), secretary of defense (Robert S. McNamara), and national security adviser (McGeorge Bundy). Kennedy’s razor-thin victory in 1960 over Republican nominee and sitting Vice President Richard M. Nixon led him to recognize the need for governing with an eye on an evenly divided electorate.

Nixon saw the wisdom in these bipartisan appointments, and when it came time to make them himself, he considered doing so in dramatic fashion.

After defeating Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey for the presidency in 1968—and by a comparably slim margin—Nixon offered Humphrey the post of ambassador to the United Nations. As he told President Lyndon B. Johnson in this phone call just over two weeks after the election, Humphrey’s appointment to the UN “would be in the interests of the country.” Nixon thought it would provide a kind of “continuum” that might help the nation, particularly with “this Vietnam thing.” Not only that, as he told Senator George A. Smathers (D-Florida), “it would give the appearance that I’m trying to . . . unify the country, which I am.”

Nixon’s election victory, like Kennedy’s eight years earlier, was a close call—at least in the popular vote—and the idea of appointing Democrats to cabinet posts—Senator Heny M. “Scoop” Jackson (D-Washington) was offered but declined the top job at the Pentagon—addressed that political reality.

Nixon went further, however, suggesting that Humphrey’s appointment would be good not only for the country’s image at home and abroad, but for Humphrey himself. The Vice President would likely be casting about for a purpose following his defeat, Nixon mused. The president-elect knew from whence he was spoke, given his own loss to Kennedy in 1960. When a fellow leaves office, Nixon said, “he’s just sort of at loose ends, and he needs something to do right away.”

Humphrey ultimately declined Nixon’s offer, explaining to Johnson that financial concerns, his reluctance at being “confined to New York,” and his interest in possibly returning to the Senate, where he had previously served for 16 years, was leading him to consider other options. But the imagery of Nixon’s proposal—a victorious presidential candidate reaching out to a defeated opponent—remains a potent symbol of national reconciliation.

The prospect of such an offer materializing after this year’s election is unlikely, given the polarization of our politics. Still, in light of the bomb threats, assassination attempts, and incendiary rhetoric infusing the current campaign, the winner this November would do well to consider the virtues of making select bipartisan appointments. Doing so might signal to members of the opposing camp, at the very least, that “We the People” means all of us.

Far from the actual border, border politics take center stage

Miller Center Professor David Leblang and his students take a deeper look at false claims against Haitian immigrants

Ever since Donald Trump descended the escalator in Trump Tower back in 2015, the Republican Party has been leveraging issues of immigration and border control. This strategy has worked: Republicans consistently outpoll the Democrats as the most trusted party on the issue of immigration and the border. As a result, the GOP has come to characterize all 50 states as “border states,” in the hope that this will resonate with their political base.

The false claim by Republican vice presidential candidate Senator JD Vance that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, are abducting and eating pets feeds directly into an age-old strategy designed to vilify immigrants and separate in- from out-groups in American society.

The allegation that Haitians–or any immigrant group for that matter–would eat house pets has a long history. An 1871 editorial cartoon refers to Chinese as “rat-eaters.” Jan Harold Brunvand documents several urban legends surrounding migrant communities, including Vietnamese wanting to “buy puppies or kittens to use as food” along with other unsavory tales.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEWhat the polls say outside the key swing states

In Sabato's Crystal Ball, Kyle Kondik takes note of other recent polls

Of all the polls that came out over the weekend, the one that seemed to get the most eyeballs from poll junkies was one that did not survey one of the seven key battleground states in this election.

Instead, the poll of interest came in Iowa, a one-time swing state that shifted hard to Donald Trump, and the poll itself was a Des Moines Register/Mediacom poll conducted by J. Ann Selzer, who has a well-earned reputation for accurate final polls in her state.

Selzer found Trump leading Kamala Harris 47%-43% in a poll released Sunday, a lead just half that of Trump’s 8-point victory there in 2020. This also was a huge shift from Selzer’s previous poll, taken in mid-June when Joe Biden was still a candidate, showing Trump up 18 points in Iowa. So while no one expects Iowa to be a prominent part of this year’s presidential battleground—it remains Safe Republican in our ratings, despite this poll—this was an encouraging finding for Democrats in a state that shares some demographic similarities with the broader Midwest (particularly Wisconsin).

READ THE FULL ARTICLEThe American berserk election

Miller Center Professor Guian McKee ponders the second assassination attempt against Donald Trump

In his 1997 novel American Pastoral, Philip Roth wrote of the “indigenous American berserk.” In the specific context of the novel, the phrase referred to the breakdown of the idealistic social movements of the 1960s into the violence of the decade’s end and the paranoia, extremism, and madness that corrupted some of the most radical of the period’s social movements.

More generally, however, Roth offered the observation, or critique, that such traits always lurk just below the surface of American society. Following the second assassination attempt on former Donald Trump on Sunday, we now run the risk that the indigenous American berserk may take control of the 2024 presidential election (full disclosure: I was inspired to write this post by Bret Stephen’s reference to Roth’s concept in the New York Times on September 16, 2024).

The indigenous American berserk is the idea that nothing is off limits, that all norms are meaningless, that the individual owes nothing to the wider national community, that belief in an idea or cause – or simply that infamy is a substitute for fame based on actual accomplishment – justifies any action, and, especially, violence. Ironically, just a few hours before the second attempt on Trump’s life, J.D. Vance articulated an elite version of the berserk when he stated on CNN that “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do.”

For Trump’s would-be assassin, the idee fixe seems to have been defense of Ukraine. His access to and knowledge of powerful weaponry, as in the Pennsylvania attempt on Trump’s life this summer, made this loosing of the berserk serious and potentially deadly.

With this attempted shooting, we are in an unfamiliar political landscape. Only once before, on October 14, 1912, have we had an attempt to assassinate a presidential candidate this close to an election (Abraham Lincoln narrowly avoided a sniper’s bullet in 1864). In that incident, former president Theodore Roosevelt faced an older version of the indigenous American berserk when an assassin, motivated by a dream in which William McKinley commanded him to kill the Progressive Party nominee, shot him in the chest.

Roosevelt personally prevented the possible lynching of the shooter and then famously told the crowd that “it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose” – and delivered his lengthy speech while bleeding from the bullet lodged in his chest.

In the aftermath, the other party nominees in the four-way 1912 race suspended their campaigns while Roosevelt recovered (a two-week period). Despite his courage in the hours after being shot, TR could not overcome his split with President William Howard Taft and lost to the Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson.

Assassins killed Robert F. Kennedy in June 1968 and badly wounded George Wallace in May 1972. Although those acts of violence reshaped both races, neither target had won their party’s nomination (and likely would not have done so).

In other words, history offers us no guide. With the indigenous American berserk untethered, we have no idea what effect yesterday’s action, or any future violence, will have on the democratic processes that the election represents. Even worse, we have no way to predict what horrors await us for the remainder of the campaign, or in the period from Election Day to the inauguration.

All we have is the norm that political violence is never acceptable. But that principle has to find its way to those susceptible to the berserk’s lure and has to convince those who feel its tug within their psyche.

Five myths about presidential transitions

Bad presidential transitions are becoming the norm, Miller Center Director and CEO William Antholis writes in The Hill

Make no mistake, the chaos of our last presidential transition was bad. No good, very bad. One impeachment and two criminal cases bad.

And yet, we are now two months away from a transition to either Trump Two or Harris One.

Former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris have each announced their transition directors. As each side begins to plan, here are five myths worth reconsidering.

READ THE FULL ARTICLEPolling error in 2016-2020: Look out for Wisconsin

Sabato's Crystal Ball Managing Editor Kyle Kondik takes a closer look at the polls

It is hardly a profound statement to say that the heavily-contested swing states in the presidential election, the septet of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, are all achingly close. Table 1 shows the state of play in all 7: We averaged the RealClearPolitics and FiveThirtyEight polling averages together to get these figures. The two averages include a different mix of polls, and RealClearPolitics uses a straight average of recent polls to come up with its numbers while FiveThirtyEight makes some adjustments.

A majority of these states (4 of the 7) either show an average lead for either candidate below a half a percentage point or is tied (North Carolina), and the largest lead—Harris’s in Wisconsin—is the only one that hits the 2-point mark, and only barely. Notice that there’s not a big difference between the current polling average margin and the actual 2020 results, although Harris is more often than not running a bit behind Joe Biden’s 2020 margins in these states. Wisconsin and North Carolina show Harris doing the best compared to the actual 2020 Biden margin.

In particular, Wisconsin polling this cycle has held up relatively well for Democrats, even though the state has been close in polls (as it remains).

READ THE FULL ARTICLEUpcoming election-related events

You can register to attend any of these events in-person or via webinar

Notes on the state of debates and primaries

Kyle Kondik writes in Sabato's Crystal Ball that though Harris may have won, memories are short

It seems fairly obvious that Kamala Harris “won” last night’s presidential debate with Donald Trump. Certainly that seemed to be the post-debate consensus, even from several right-leaning commentators. A CNN flash poll of debate watchers found that 63% thought Harris did a better job in the debate, and 37% thought Trump did.

This is a decently-sized disparity for a poll like this, although the difference between the two candidates was larger in the June debate that eventually forced Joe Biden from the race (67% thought Trump did better while only 33% thought Biden did) and the first debates between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama in 2012 (67%-25% Romney) Hillary Clinton and Trump in 2016 (62%-27% Clinton), and Biden and Trump in 2020 (60%-28% Biden). CNN’s Harry Enten also noted that the viewership for this Harris-Trump debate, as observed in the poll, was Republican-leaning, which may have had an impact on the poll findings. It’s also worth remembering that judging someone to have won a debate is different than voting for that person: A couple of the aforementioned big winners of previous first clashes between candidates (Romney in 2012 and Clinton in 2016) didn’t end up winning the actual election.

Democrats will come out of last night feeling better about what happened than Republicans will. That could have at least some short-term implications for the horse race, which is absurdly close in the polls (we’ll have more to say about the polls in tomorrow’s Crystal Ball). We would advise against jumping to strong conclusions about a changed race based on immediate changes in the numbers, if such changes materialize. Some longer-term growth for Harris is possible, though—there’s been some recent discussion of polling floors and ceilings, and it does seem reasonable to suggest that Harris may have a higher ceiling than Trump, if she is able to reach it (Michael Podhorzer, former political director of the AFL-CIO and a shrewd elections commentator on the left, recently pointed out some of this growth potential for Harris).

READ THE FULL ARTICLEHarris passed the test

Miller Center Director & CEO William Antholis assesses the debate

Presidential debates tend to be about three things: staying on message, throwing and taking punches, and looking good. That was the baseline to measure both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump last night.

But Kamala Harris had an additional task, which made her job harder. For candidates new to the American people, it's also about proving that you can become commander in chief. Of course, she is the sitting vice president of the United States, and he is the challenger. And yet because he already has been commander in chief and she hasn't, she had to demonstrate that she could look the part, talk the talk.

That's a challenge Jimmy Carter had when facing Gerald Ford, and he passed.

That's a challenge Ronald Reagan had when facing Jimmy Carter, and he passed.

Same for Bill Clinton against George H.W. Bush, for George W. Bush against Al Gore, for Barack Obama against John McCain, and for Donald Trump against Hillary Clinton.

Harris passed that test last night. Passing that test will not guarantee her the election. Just ask President Walter Mondale, who won his first debate against Reagan.

But if she had not passed the test, she could easily have lost the election. Just ask President Mike Dukakis.

As for the three common tasks for both candidates, they each had their moments.

In terms of staying on message, they both had strong opening and closing remarks, sticking closely to their stump speech greatest hits--Harris focused on a future oriented message, Trump focused on Biden-Harris failures.

In terms of throwing punches and taking punches ... they both threw punches, even if Trump seemed rattled enough to talk about immigrants eating pets.

Finally, in terms of how they looked--she spoke of joy and optimism, he spoke of her failings with energy and anger. Those opposing looks were aimed squarely at undecided voters.

For some untold number of those undecided voters, Harris showed that she could share the stage with Trump. That's a small but meaningful moment as the American people continue their job interview with both of them.

Debates can make a difference

Mary Kate Cary, an adjunct professor in UVA's Department of Politics, recalls the Bush-Dukakis debate in 1988

Axios ran a piece this morning entitled “Harris to Have a Shorter Debate Podium than Trump’s,” which ended with this tidbit:

Flashback: Other presidential candidates have been worried about looking small in debates compared to their taller opponents. In 1988, former Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis (5 foot 9) was worried about his stature against then-Vice President George H.W. Bush, who was 6 foot 2. Dukakis requested a boost, recalled Frank Fahrenkopf, co-chair of the Commission on Presidential Debates. "We built something like a pitcher's mound behind Dukakis' podium for him to step on," he told Axios. Dukakis did not respond to a request for comment.

That reminded me of the following weekend’s Saturday Night Live skit, where Jon Lovitz’s Michael Dukakis uses a hydraulic lift to get taller behind the podium (start at the 1:00 mark) at the start of the debate with Dana Carvey’s George HW Bush.

As a staffer on the Bush-Quayle campaign, I was at that second Bush-Dukakis debate, held on October 13, 1988. The evening opened with a question from CNN’s Bernard Shaw to Governor Dukakis, asking if Kitty Dukakis had been raped and murdered, would he still be opposed to the death penalty? Dukakis doesn’t bat an eye, says he remains opposed to the death penalty, and goes on to talk about waging the war on drugs, reducing crime, and promoting drug education.

That same SNL skit shows Kevin Nealon caricaturing Sam Donaldson, asking the first question to Dukakis (2:08 mark), inquiring as to whether Dukakis has the passion to be president, or if he’s a “bit of a cold fish.” Dukakis becomes “enraged” — barely reacting at all — and Lovitz’s performance encapsulated what everyone saw days earlier at the real debate. It’s worth a watch all these years later.

Dukakis had been sliding in the polls after leading by 17 points after the Democratic convention, and the second debate was his chance to turn his fortunes around. But that answer made a big difference. Two weeks later, Dukakis lost to Bush by just under 8 points in the popular vote, and 111 to 426 in the Electoral College. No candidate since Bush in 1988 has managed to pull off as big a win in the electoral or popular vote.

Years later, Dukakis gave an interview to former Miller Center board member Jim Lehrer about the make-or-break nature of presidential debates. “I thought I did a pretty good job in the first debate, not a very good job in the second debate. And I think, had I done a better job, particularly in that second debate, it might have made some difference. Now, how much, I can't tell you … The lesson of '88 is, in a general sense, if the other guy is going to come at you, you better be ready for it, you better have a very clear sense of how you are going to deal with it and that has to be part of your overall campaign as well as what you do at the debate itself.”

Five things to watch in Tuesday's debate

UVA political science professors Jennifer Lawless and Paul Freedman preview the faceoff between Trump and Harris