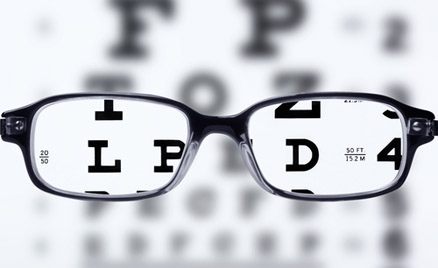

Treating America’s Fiscal Myopia

This series of Volume 3 response posts are written by former Miller Center fellows who offer their perspective on the topic of fiscal policy and how to best prepare the next president for the challenges of the first year. This series is coordinated and edited by Christy Ford Chapin, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Among the many challenges that a new president will face, tackling the nation’s fiscal future will be among the most difficult. As the many essays in this collection of The Critical First Budget show, there are several factors that are likely to shape what is possible. From the structural aspects of an anemic economic recovery amidst growing inequality, to the unsustainable demands of entitlement spending, to the desire to have fiscal policy reflect shared social values, the next president will need to address numerous aspects of our tax and spending policies.

For too long, U.S. lawmakers have been preoccupied with addressing the nation’s fiscal woes by focusing almost exclusively on tax policy. While Republicans believe that top-end tax cuts can spur economic growth, Democrats contend that “soaking the rich” is one way to raise revenue and challenge inequality. Both sides have tended to fixate on tax rates for the wealthiest Americans without considering the direct connection between the two sides of the ledger—that is, between tax and spending policies. For the most part, policymakers have failed to present budget issues to voters in a comprehensive manner that helps them connect rising revenues with strengthened government benefits and economic security or, in the reverse, lower taxes with frailer federal assistance and program cutbacks.

Although spending cuts and entitlement reform have in recent years gained some traction, even these proposals are often discussed in isolation from tax policy. As the analysis by William Gale and Aaron Krupkin illustrates, there are stark distinctions between our two national parties when it comes to taxing the rich. But they share a fixation in focusing on taxes at the top end. Rarely do our political leaders think about how our tax and spending policies work as a whole. Instead, they seem to focus narrowly on tax or spending policies in isolation. One example of that is the preoccupation with high-end progressive taxation.

The American obsession with high-end progressivity can be traced back to the early twentieth-century origins of the U.S. progressive income tax. That was when progressive intellectuals and lawmakers helped build a modern American fiscal state that was premised on recalibrating the prevailing system of taxation by enacting direct and graduated taxes on incomes and wealth-transfers. As Thomas Piketty has suggested, “confiscatory taxation of excessive incomes” was an “American invention.”

Piketty may have exaggerated the exceptionalism and degree of U.S. progressive taxation, but his observation acutely describes the beginnings of the American obsession with “soaking the rich.” In a new research project, Joseph J. Thorndike and I are synthesizing some of our prior research on American fiscal history to explore “The Long Twentieth-Century American Commitment to Progressive Taxation.” We chronicle how the United States developed one of the most progressive tax systems in the world. High-end graduated taxes based on the notion of “ability to pay,” we argue, became the touchstone of American tax policy throughout most of the twentieth century.

Yet one of the unintended consequences of this historical process has been the neglect of the spending side of the tax-and-transfer system. By focusing narrowly on revenue extraction—on who pays what—past reformers overlooked how progressive public spending could counter the regressive incidence of certain taxes. By ignoring the modern state’s potentially tremendous spending powers, an earlier generation of political leaders created a type of fiscal myopia that has continued to afflict American policy making.

The next president could help treat this enduring myopia. One way to do so would be to look globally to see how other advanced industrialized nations have challenged inequality. They have done so not by focusing exclusively on progressive taxation, on “soaking the rich.” Rather, other countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden have used broad-based regressive taxes on consumption, like the value-added tax (VAT), to generate robust public revenues that, in turn, can be used to underwrite a variety of egalitarian social-welfare programs, from investments in education to national health care to childcare. Some observers might argue that consumption taxes like the VAT may be regressive, falling more heavily on the poor and middle classes than the rich. However, in Europe, the revenues associated with a regressive VAT have funded progressive programs that have disproportionately favored poor and lower-income families that otherwise would have had less access to social-welfare programs.

In recent years, some U.S fiscal policy analysts have suggested establishing a tighter link between the American tax-and-transfer systems. They have recommended, for example, that the United States adopt a general, yet moderate, VAT on all goods and services to pay for skyrocketing healthcare costs. The revenues generated by such a VAT could be used for progressive spending policies, such as funding the spiraling costs of Medicare and Medicaid—a policy that would benefit the poor and middle classes to a larger degree than the rich.

While ideas like a healthcare VAT remain controversial, a new president with the right amount of political and social capital may be able to propose such bold and ambitious reforms. They may not work at first, but there is an art to losing that suggests that initial setbacks can lay the foundation for future success. Although President Bill Clinton failed to pass comprehensive health care reform, some might argue that the proposal and accompanying debates primed voters, policymakers, and interest groups to be more accepting of President Barak Obama’s subsequent, successful healthcare reforms. If the next president is to transform “magical fiscal thinking” into reality, if they are to treat the American case of fiscal myopia, he or she will need to take a chance on similarly bold and ambitious reforms.

Ajay K. Mehrotra is Executive Director and Research Professor at the American Bar Foundation, an independent research institute based in Chicago, Illinois. He is the author of Making the Modern American Fiscal State: Law, Politics and the Rise of Progressive Taxation, 1877-1929 (2013), and the co-editor (with Monica Prasad and Isaac William Martin) of The New Fiscal Sociology: Taxation in Comparative and Historical Perspective (2009).