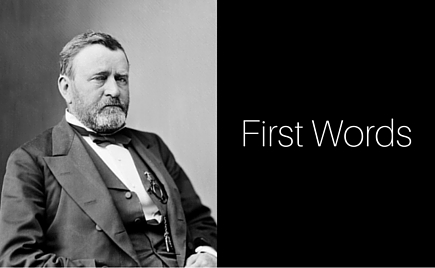

First Words: Ulysses S. Grant, March 4, 1869

In this ongoing series, the Miller Center’s First Year Project looks at key phrases from past inaugural addresses—the first words spoken by our new presidents. Today we look at Ulysses S. Grant.

The election of 1868 was the first following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. After three years with the uncharismatic Andrew Johnson in the White House, the nation continued to struggle with Reconstruction—the efforts to bring the shattered South back into the Union. Grant came to believe that the federal government had to preserve the sacrifices of the war by protecting African Americans from racist Southern governments and preventing former Confederates from retaking power. With the support of the Radical Republicans, who shared this view, Grant easily won his party’s nomination and the presidency.

As he came into office, Grant sought to remain above politics, and he was determined to follow Lincoln’s policy of reconciliation with the South even as he maintained his determination to protect formerly enslaved African Americans.

The country having just emerged from a great rebellion, many questions will come before it for settlement in the next four years which preceding Administrations have never had to deal with. In meeting these it is desirable that they should be approached calmly, without prejudice, hate, or sectional pride, remembering that the greatest good to the greatest number is the object to be attained.

. . .

To protect the national honor, every dollar of Government indebtedness should be paid in gold, unless otherwise expressly stipulated in the contract. Let it be understood that no repudiator of one farthing of our public deb twill be trusted in public place, and it will go far toward strengthening a credit which ought to be the best in the world, and will ultimately enable us to replace the debt with bonds bearing less interest than we now pay.

. . .

The young men of the country—those who from their age must be its rulers twenty-five years hence—have a peculiar interest in maintaining the national honor. A moment's reflection as to what will be our commanding influence among the nations of the earth in their day, if they are only true to themselves, should inspire them with national pride. All divisions—geographical, political, and religious--can join in this common sentiment.

…

The question of suffrage is one which is likely to agitate the public so long as a portion of the citizens of the nation are excluded from its privileges in any State. It seems to me very desirable that this question should be settled now, and I entertain the hope and express the desire that it may be by the ratification of the fifteenth article of amendment to the Constitution.