Making the Teapot Dome scandal relevant again!

President Trump can learn from Harding’s disaster

As Donald Trump is looking to roll back environmental regulations, lease more public lands, and re-organize government to follow business practices, he would be wise to remember the Teapot Dome scandal of 95 years ago, the biggest presidential scandal until Watergate.

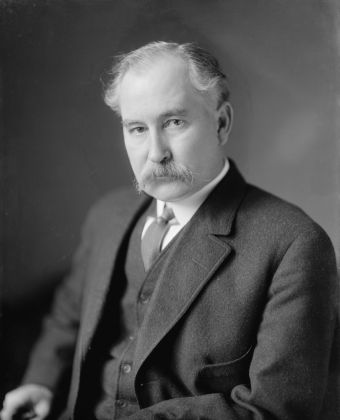

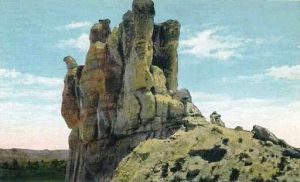

On April 7, 1922, President Warren G. Harding’s secretary of interior, Albert Fall, leased the oil reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyoming to Harry Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Company. Several weeks later, Fall leased more reserves at Elks Hill in California to Edward Doheny of the Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company. The deals were done in secret, and Fall was later convicted of taking a $100,000 bribe—the only cabinet officer ever to be found guilty of a crime. The scandal trashed Harding’s reputation.

The Teapot Dome story is not just about profits and corruption, however. It’s about geopolitics, anti-Progressive ideas, and Washington party politics.

When Harding was elected, one of his primary goals was to reorganize government as part of the “return to normalcy” in the wake of an enlarged bureaucracy at the end of the Great War. For Secretary Fall, this meant moving the US Navy’s oil reserves to the interior department. On May 31, 1921, Harding signed Executive Order 3474, which Fall wrote.

The conservationists were upset, but the Harding administration was more concerned with changing geopolitics and threats to national security. By 1920, the United States exported 80 percent of the world’s oil, and the US Navy had converted its ships’ engines from coal to oil. The rise of the automobile also increased oil demand. Experts believed that the oil reserves would be depleted in 10-20 years, and the public thought the country was losing out on oil deals in Latin America, the Middle East, and the Dutch East Indies.

Secretary Fall differed significantly from President Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), a Republican and one of our nation’s most famous conservationists. Fall would feel more at home in today’s Republican Party as he saw regulations as an impediment to jobs and development. He was a product of the western frontier of New Mexico, made his money as a lawyer representing timber, mining, and oil companies, and hated bureaucrats.

Although the Teapot Dome and Elks Hill leases were done in secret, newspapers quickly broke the news, and Senator Robert M. La Follette (R-WI) began to investigate. In response, Harding wrote a letter to the Senate saying he approved of the lease policy. Now the president was directly linked to the developing scandal.

The investigations continued after Fall resigned on March 4, 1923, as another senator, Thomas Walsh (D-MT), began to look into the matter. Walsh found out that Mammoth Oil’s Sinclair had invested in Fall’s New Mexico ranch, and that Fall received $100,000 from Pan American’s Doheny. In January 1924, Doheny testified it was a personal loan, not a bribe, but senators began to wonder if the loan gave him unfair access to the oil reserves.

In his second Senate appearance, Fall pleaded the Fifth Amendment, and he would later be convicted of bribery and sentenced to one year. Doheny and Sinclair, the two oilmen, never were convicted, but their leases were cancelled and they lost millions.

The Teapot Dome lease and the loan were never illegal in and of themselves, but the unsavory nature of the deal left Republicans needing a scapegoat, and the Democrats used the scandal as an effective election issue.

What can President Trump learn from the scandal?

Transparency. When your administration does lease public land or handle private company transactions, be transparent as possible.

Be aware of what your cabinet members/friends are doing. Millionaire money began to blur into personal lines for Fall. Also, Harding supported Fall’s efforts, but he was not strategic enough to see the backlash. Public outcry grew worse when it was revealed that Doheny liked to hire many former cabinet officers like Elihu Root, William McAdoo, and Fall. Ironically, the downfall came from a Republican Congress.

Image is important. Thanks to the Teapot Dome and other major scandals, Harding’s reputation still ranks near the bottom. Even though the president was not personally involved in any of the scandals, he owned them. Calvin Coolidge was smarter. He distanced himself from the scandal-ridden cabinet officers, and moved ahead of the Senate when he announced an independent prosecutor, sending the whole thing to the courts, all before the Senate could pass its own resolution.

President Trump’s policies do have some similarities to Harding’s: reorganizing government along business practices and uprooting conservation policy. Time will tell how far Trump's reputation will rise or fall.