The urgency of energy

Previous administrations offer lessons for first-year energy policies

Memorandum to President Trump

Subject: Lessons from previous presidents’ first-year energy initiatives

You came into office with a long list of goals for your new administration, and with political capital that you can spend to make them happen. Among the areas of policy that you focused on during your campaign was energy. Given the extent to which the energy landscape has shifted over the past decade, our nation’s energy policies are ripe for review and updating. With no new comprehensive energy legislation having passed during the Obama Administration, the start of your term might appear to offer a new opportunity to propose comprehensive energy legislation to address our changing world.

You should consider the lessons that can be drawn from the attempts of previous presidents to implement significant new energy policies.

But even a new president’s political capital is limited, as is an administration’s bandwidth to pursue significant new legislation. Before deciding how to proceed on the energy policy front, you should consider the lessons that can be drawn from the attempts of previous presidents to implement significant new energy policies in their first years in office.

A review of these experiences since President Gerald Ford reveals that several sought to reshape U.S. energy policy at the start of their administrations. Some proposed legislation. Others exercised executive authority. Others still focused on developing a comprehensive energy plan. As you have seen in your own executive order regarding pipelines, there are few obstacles to a president developing a plan or exercising authority through the regulatory or budgeting processes. In contrast, legislation near the start of a president’s term is more difficult to achieve, particularly with other priorities vying for the limited attention of Congress. However, if an administration uses its first year to plan, then legislation later in a term can have long-term positive effects if crafted in a strategic and bipartisan fashion.

Between the period during which the nation was electrified and the 1970s, the availability of ample supplies of energy was largely taken for granted. Energy policy was therefore accorded little priority by presidents and senior policy makers. Relative inattention to energy, however, ended with the Arab oil embargo and the resulting spike in oil prices that led the nation into recession. Within weeks after the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) increased the posted price of crude oil by 70 percent and initiated an embargo on the sale of crude oil to the United States, President Richard Nixon addressed the nation, announcing his Project Independence, with a primary goal of meeting all of our own energy needs by 1980. He also called for emergency legislation that would reshape our energy landscape and for immediate passage of pending legislation that would authorize construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which was enacted within a week. Much of the remainder of his energy agenda, however, was left for Ford to address.

Ford administration: A framework for the future

Entering office in the middle of an energy-induced recession, Ford made energy a centerpiece of his first State of the Union address. He called for a substantial reduction in the volume of imported oil, supported by an oil import fee; a reduction in the risk of economic disruption by foreign oil suppliers; and development of the capacity to supply the free world with much of its energy by the turn of the century. He sought to end price controls on domestic oil to promote production and establish a new tax on oil companies in response to public concerns that they were profiting off of high oil prices. He supported drilling offshore and in Alaska, construction of new nuclear power plants, establishment of building efficiency standards, and legislation to modify and defer automotive pollution standards for five years so industry could focus on improving automobile gas mileage by 40 percent by 1980.

While negotiations with Congress were difficult, the national sense of crisis effectively required the president and Congress to act. By the end of 1975, Ford signed the landmark Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 (EPCA) that, among other things, established the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the first automotive fuel economy standards, the first appliance efficiency standards, and a reduction in the price of oil along with authority to phase out price controls over the next several years. Nearly every one of these steps has maintained bipartisan support over the last four decades.

In signing the legislation, however, Ford noted the need for further legislation to deregulate natural gas, make homes more efficient, support development of synthetic fuels, and permit greater use of nuclear power—ideas that Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan pursued during their administrations.

Carter administration: Far-sighted but controversial

Just 13 months after enactment of EPCA, Carter entered office with the nation still in the midst of turmoil in the energy sector. The country was still suffering the aftereffects of the 1973– 74 oil embargo, and there was continued concern that oil markets would tighten well into the next decade—a fear that was reinforced as oil prices rose sharply during his administration as a result of the revolution and turmoil in Iran.

In addition to the longer-term concerns related to our use of oil, as Carter entered office, cold temperatures in the eastern United States and flawed laws governing natural gas production and prices led to widespread natural gas shortages, which closed factories and schools across large parts of the nation, leaving hundreds of thousands of students and factory workers at home in January 1977. In response to that acute crisis, the first bill that Carter signed into law, less than two weeks after entering office, was emergency natural gas legislation, which allowed the government to direct the transfer of natural gas around the nation to where it was needed most.

Carter addressed the nation from the Oval Office about our larger energy crisis in April 1977, and addressed a joint session of Congress two days later, requesting passage of comprehensive energy legislation, including establishment of the Department of Energy.

Congress established the new Department of Energy by the fall of 1977 and restructured the Federal Power Commission into the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

After 18 months of debate and negotiation, Congress also passed the National Energy Act of 1978, which touched much of the nation’s energy landscape. The act restructured the regulation of natural gas production, pricing, and allocation to promote increased production; facilitated small power production facilities and cogeneration; established tax credits for energy conservation and the production of renewable energy; established a gas guzzler tax on inefficient cars; limited the use of natural gas and oil in power plants and major industrial facilities; and offered financial support for weatherization of schools, hospitals, and low-income households to improve energy efficiency.

In response to a national sense of crisis over our energy future . . . Carter and Congress responded with a set of comprehensive policies.

While the wisdom, and ultimate success, of many of the elements of the legislation remains controversial—especially price controls—it is beyond doubt that in response to a national sense of crisis over our energy future at the time he entered office, Carter and the Congress responded with a set of comprehensive policies that they believed would enhance American security and strengthen the economy.

Reagan administration: Regulatory rollback

Although Reagan entered office in a period of high oil prices and uncertainty stemming from the start of the Iran-Iraq War in September 1980, he took a distinctly different approach to energy policy, one that was consistent with his support for smaller government and less regulation. He believed that the United States had a vast reservoir of untapped conventional energy resources and that their discovery and production was impeded by federal government regulation. A week into his presidency, Reagan exercised executive authority to eliminate price and allocation controls on domestic oil and gasoline production and distribution in an effort to “promote prudent conservation and vigorous domestic production.” Elimination of price controls was consistent with his general approach to governing, reflected in his call to allow the “native American genius, not arbitrary federal policy, to be free to provide for our energy future.” That same week he reiterated his desire to close the Department of Energy, proposing legislation to do so in early 1982.

Nuclear power was one area in which Reagan called for new government support during his first year. With oil being phased out as a fuel to generate power, and the natural gas markets still evolving after the passage of the National Energy Act, he maintained a hope that nuclear power would help meet America’s power needs, despite the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island. In the fall of 1981, Reagan undertook several policy initiatives in support of nuclear power, including directing the Department of Energy to recommend an approach to waste disposal, then viewed as a critical challenge. Following their recommendation in early 1982, he proposed legislation that was passed late that year that established a federal commitment to long-term geologic disposal, managed by the federal government but paid for by utilities.

George H. W. Bush administration: Action without controversy

When President George H. W. Bush entered office in 1989, energy policy was not an area of significant public interest. Oil prices had collapsed in 1986 and energy prices were stable; supplies appeared ample and there was little public attention to energy issues.

In the summer of 1989, Bush called on the Department of Energy to develop the National Energy Strategy in response to concerns that conservation efforts were lagging, domestic oil production was declining and imports were growing, and environmental concerns were not a sufficient priority. The urgency of this effort grew after Iraq invaded Kuwait and the security of U.S. energy supplies once again appeared to be in peril.

In February 1991, Bush released his strategy and proposed legislation that emphasized support for increased oil and natural gas production, including production in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, as well as nuclear power. As the oil price spike after the invasion of Kuwait abated relatively quickly, the focus of energy legislation shifted from increasing conventional production to supporting energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies, and promoting the practice by electric utilities of “integrated resource planning,” which included the consideration of utility-sponsored efficiency programs. The legislation also amended the Federal Power Act to lay the groundwork for utility restructuring and competition.

In the absence of the sense of crisis at the start of his term that Ford and Carter had faced, Bush instead called on his administration to prepare an energy strategy. In doing so, he laid the groundwork for passage of legislation later in his term after the Gulf War created a greater sense of urgency, although the changing energy landscape may have left him with legislation whose vision differed from what he contemplated when he called for the creation of an energy strategy three years earlier.

Clinton administration: Controversy without urgency

Likewise, there was no sense of urgency or crisis about energy policy at the start of President Bill Clinton’s term. After the relatively brief spike in gasoline price during the Iraq War, prices were stable and low, and public attention was focused on the economy. Clinton did not develop a comprehensive energy plan or legislation; he did, however, propose a broad-based BTU tax in February 1991, to help fund part of his deficit reduction plan. He chose a BTU tax as a funding source because it would encourage conservation and reduce pollution without targeting any particular region of the country.

Industry and consumers, however, opposed the BTU tax, and the Senate rejected it. The only remnant of the proposal that was enacted was a 4.3-cent-per-gallon increase in the gasoline tax to help fund the Highway Trust Fund—a tax that also proved politically unpopular. The Clinton Administration also proposed comprehensive legislation to reform the electric power industry in 1999, but with no sense of urgency, the legislation languished.

George W. Bush administration: A comprehensive production plan

Between 1999 and 2000, the nation endured a period of sharply rising gasoline prices as a result of OPEC production cuts. By the time President George W. Bush entered office in 2001, however, the price spikes had abated, and there was greater concern about the economic slowdown at the start of the year (and the recession that began in April) than there was about energy. While the California energy crisis peaked around the time Bush entered office, it was generally viewed as the result of a flawed experiment in California rather than a reflection of a greater national problem.

Nevertheless, Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney both had backgrounds in the oil sector and had significant interest in energy policy. At Bush’s direction, Cheney led a high-profile task force that assembled a concise and comprehensive energy plan that outlined their vision for a production-oriented energy policy. The report, issued in May 2001, served as the springboard for the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which was enacted shortly after oil first passed through the threshold price of $60 per barrel. A second piece of comprehensive energy legislation, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, was enabled primarily as a response to the price of crude oil surpassing the $100-per-barrel milestone shortly before the start of a presidential election year.

Obama administration: Clean energy amid a recession and recovery

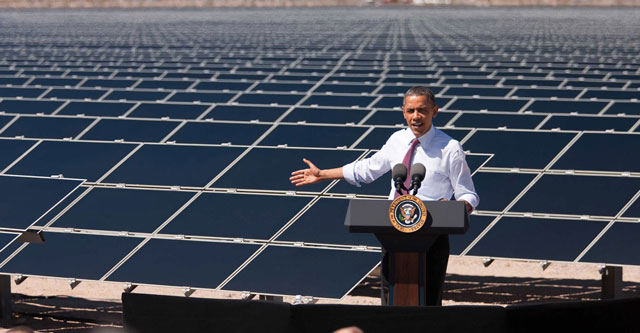

President Barack Obama entered office in the midst of the Great Recession, and his primary concern was reviving an economy that was teetering on the brink of depression. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a massive stimulus bill intended to promote economic recovery, included approximately $90 billion in clean energy–related spending. Although the stimulus was not comprehensive energy legislation, it did represent one of the most important statements of energy policy and priorities in recent years. Obama did not propose his own legislation to cap carbon emissions, but he did support comprehensive cap-and-trade legislation that passed the House early in his first term, although it failed in the Senate.

Addressing climate change was a central goal of Obama’s second term. While the centerpiece was the Clean Power Plan—EPA rules promulgated under the authority of the Clean Air Act to reduce power plant emissions—the president also developed rules to reduce methane emissions and improve appliance efficiency, and he helped reach international consensus to address climate change. Nevertheless, he supported responsibly growing domestic production of oil and gas, streamlining the process to authorize the export of natural gas, and reaching agreement with Congress to end the ban on crude oil exports, while also extending federal support for production of renewable energy.

Addressing climate change is closely related to energy issues, but if the success of legislation to address carbon emissions is predicated on the necessity of a crisis to build political support, that may foretell a difficult path. Unlike energy crises, which can be acute, we are unlikely to experience a quick and sharp climate crisis that might build public support for climate legislation as energy crises have built support for energy legislation.

Conclusion

Most successful energy-related legislative initiatives were driven by a national sense of urgency brought on by some type of energy crisis.

The experiences of most presidents in their first years since the 1973 energy crisis reveal that most successful energy-related legislative initiatives were driven by a national sense of urgency brought on by some type of energy crisis. When presidents proposed or supported significant new energy policies when there was little sense of crisis, such as in 1993 and 2009, they failed. At the same time, when presidents entered office when there was no sense of crisis, in 1989 and 2001, and developed comprehensive energy plans, those plans formed the basis of legislation that passed when opportunities arose later in their terms. Presidents have greater latitude to undertake actions using existing statutory or administrative authority, such as Reagan’s elimination of oil price controls in January 1981, but there are generally limits to what a president can do without legislation.

The key lesson appears to be that in the absence of an energy crisis near the start of your term, a better approach may be to spend political capital in support of other priorities but to prepare a comprehensive energy legislative agenda so that if a crisis situation arises, you can use the opportunity to help implement it.