The Crucible

The pivotal relationship between Lincoln and the abolitionists

Adapted from Chapter Two of Rivalry and Reform, by Sidney M. Milkis and Daniel J. Tichenor

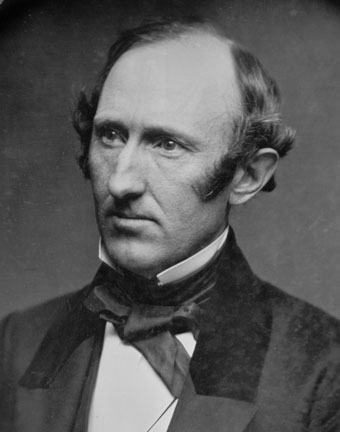

By the summer of 1862, the Republican Party was united in the view that Lincoln and the military should take all action, including emancipation, to put down the rebellion. Even moderate Republicans supported the enactment of two laws that made all but inevitable the link between restoration of the Union and emancipation. The Militia Act not only called for a draft of soldiers for nine-month tours of duty, but also empowered the president to enroll “persons of African descent” for any “war service for which they may be found competent,” including service as soldiers, a step that Lincoln was not yet prepared to take. This revolutionary provision was underscored with Congress’s enactment of a second Confiscation Act, which punished “traitors” by confiscating their property, including slaves who were “deemed captives of war . . . and forever free.” Lincoln received numerous letters, even from self-proclaimed opponents of slavery, urging him to veto the second Confiscation Act, arguing, as the president once had himself, that it would undermine rather than strengthen the Union effort. As one such missive warned, “By adopting the policy of this bill, you will no longer be considered by the American people, as the President of the mighty republic of the United States; but as the head of the Abolition faction, warring for the destruction of slavery. . . . It is high time, that a stop be put, to the Jacobin cant, ‘slavery must die, that the republic may live.’ ”

Lincoln also had deep reservations about the sweeping powers the bill bestowed on the military; he ultimately signed the legislation, but took the extraordinary step of sending back to Congress a draft veto message that detailed his concerns about its failure to clearly stipulate the meaning of treason and to distinguish between Confederates’ real property and slaves. Nevertheless, recognizing that to resist the rising sentiment for abolition would unite his partisan brethren in Congress against him, Lincoln not only signed the Confiscation Act, but also made no effort to resist the pressure that the Committee on the Conduct of the War put on generals to aggressively enforce it.

Spurred by the radicals of his party and frustrated by the border states’ adamant rejection of his plan for compensated emancipation, Lincoln finally tilted toward the abolitionist position. He privately consulted with various confidantes, including moderate abolitionists, about issuing an emancipation proclamation as a military measure liberating slaves behind Confederate lines. A draft of a proclamation was soon prepared and locked in his desk drawer. When Sumner persistently urged Lincoln to issue the proclamation, the president firmly explained, “We mustn’t issue it till after a victory.” To begin preparing Northern sentiment for such an order, he resuscitated his colonization proposal as a way of assuaging popular fears that emancipation would lead freed slaves to resettle en masse in Northern states. He also issued his famous public response to Horace Greeley’s New York editorial, titled “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” that criticized the president’s lethargy on emancipation. Lincoln’s open letter clarified what he saw as his official obligation to subordinate the slavery question to preserving the Union. If carrying out these official duties frustrated the abolitionist cause, they represented “no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.” His open letter was designed to reassure Northerners “who did not want to see the war transformed into a crusade for abolition,” and alert “antislavery men that he was contemplating further moves against the peculiar institution.

Lincoln continued to fret in coming days about whether the emancipation order was too radical for public opinion or might drive border states into the Confederate fold. He confessed to a delegation of Chicago abolitionists that it was his “earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter.” To his cabinet, Lincoln explained that he had “made a vow, a covenant, that if God gave us a victory in the approaching battle,” he would consider it “an indication of Divine will” that he issue the proclamation. That the will of God now became a consideration in the president’s actions over slavery “was an odd situation for a man like Lincoln whose religious views were, to say the least, unorthodox.” In truth, as Lincoln would later suggest in his magisterial second inaugural, he believed that divine intention was inscrutable. Yet the defense of his proclamation as a religious covenant more than likely expressed Lincoln’s recognition that the antislavery jeremiads of activists like Garrison—the view that the war was a reckoning for the sin of slavery and that God intended the president to free the slaves—now resonated powerfully in the North.

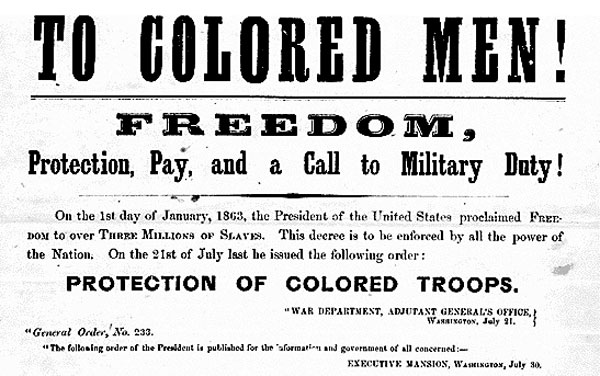

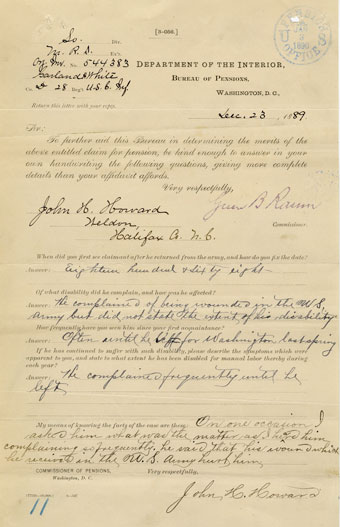

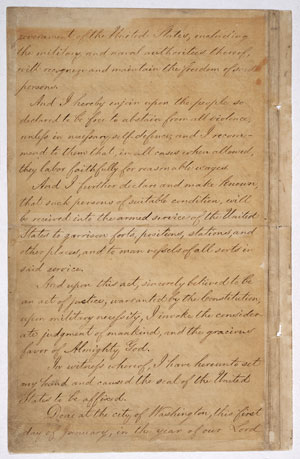

Abolitionists, even as they celebrated the “wonderful, wonderful, wonderful change that had taken place in national affairs . . . under the pressure of irresistible necessity,” vowed to encourage the president in his divine inspiration. As the delegates to the Convention of the New England Anti-Slavery Society pledged in June 1862, “Whatever may be the providential advancement of our cause, however emancipation might come, more or less extensively as military necessity, or as a work of political expedience, our work is the preaching of righteousness to it.” Abolitionists thus prepared the moral ground that would burnish Lincoln’s appeal to the exigencies of war. When military victory finally came at Antietam in September, Lincoln issued a “Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation” followed by a permanent proclamation a few months later. The centerpiece of the executive order was its declaration of presidential intent to emancipate all slaves in areas failing to return to the Union by January 1, 1863. Using language consistent with his constitutional role as commander in chief, Lincoln defined emancipation in terms of military imperative; the proclamation was to be applied essentially in unconquered sections of the Confederacy. Slaves also were described in martial terms as commodities of war; their freedom was “not a question of sentiment or taste, but one of physical force, which may be preserved and estimated as horsepower, and steampower, are measured and estimated.”