Nixon and the Pentagon Papers

Why President Richard Nixon was deeply concerned—perhaps even obsessed—with leaks related to Johnson administration policies

In early 1967, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara was struggling with a mounting sense of frustration over the Vietnam War. Questioning the decision-making process that had led to such deep US involvement, McNamara initiated a comprehensive analysis of post-1945 policy in the region. So began the creation of what would come to be called the "Pentagon Papers."

By June, the Vietnam Study Task Force was officially at work under the direction of Leslie H. Gelb, the director of Policy Planning and Arms Control for International Security Affairs at the Department of Defense.

A year and a half later, Gelb’s team of 36 military personnel, historians, and defense analysts from the RAND Corporation and Washington Institute for Defense Analysis had produced roughly 7,000 pages comprising 47 volumes.United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967 was a comprehensive documentary and analytical record from the end of World War II through the aftermath of the Tet Offensive of early 1968. Most important, however, the highly classified study revealed that administrations from Harry S. Truman's through Lyndon B. Johnson's had willingly deceived the American people about the nation's involvement in Vietnam.

[The Pentagon Papers represented] a body of authoritative information, of inside government deliberations, that demonstrated beyond questioning the criticisms that antiwar activists had been making for years not only were not wrong but, in fact, were not materially different from things that had been argued inside the US government.

Historian John Prados

As with most classified documents, McNamara’s detailed study might have gathered dust for decades. Instead much of it appeared in the New York Times, and its publication became a turning point in the presidency of Richard Nixon—an ironic twist considering the Pentagon Papers covered a period when Nixon himself was not in power.

Nevertheless, the leak occurred during the Nixon presidency, convincing him that he was engaged in the battle of a lifetime—to protect his presidency as well as the nation. In his eyes, the publication of the Pentagon Papers confirmed the existence of a radical, left-wing conspiracy throughout the government and media, whose purpose was to delegitimize him and topple his administration.

Nixon resolved to fight back with every tool at his disposal, making the fateful decision to break the law to achieve his ends.

In 2010 Daniel Ellsberg, Les Gelb, and James Goodale discussed the Pentagon Papers at an event hosted by the Columbia Journalism Review.

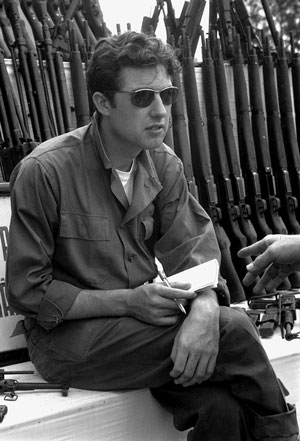

The story of the Pentagon Papers begins with Daniel Ellsberg, a defense analyst specializing in nuclear weapons strategy and counterinsurgency theory. Ellsberg had deep knowledge of Vietnam, having served in the Pentagon's International Security Affairs (ISA) division from 1964–65 then as an analyst in South Vietnam for two years. After returning to the United States to work for the RAND Corporation, he became a member of Gelb's task force. The work confirmed what he already suspected: US involvement in Vietnam was based on systematic deception by the government. As the Nixon administration pursued its own policy in Vietnam, Ellsberg became increasingly frustrated, seeing a continuing pattern of deceit and escalation, and he began to consider leaking the study.

Over the course of several weeks in the fall of 1969, Ellsberg managed to sneak out and photocopy the study with the help of another former RAND employee. After moving to the MIT Center for International Studies, he made the final decision to leak it.

Initially Ellsberg turned to members of Congress such as Senator J. William Fulbright [D-AR], Senator Charles Mathias Jr. [R-MD], Senator George McGovern [D-SD], and Congressman Paul (Pete) McCloskey Jr. [R-CA] in the hope that one of them would be willing to enter the Pentagon Papers into the Congressional Record. All four declined. But Ellsberg’s efforts were not entirely fruitless. McGovern suggested he provide his copies to either the New York Times or the Washington Post. In March 1971, Ellsberg showed the study to Times reporter Neil Sheehan.

The Times knew the story was big. Sheehan and a few select colleagues sequestered themselves in the New York Hilton to sort through thousands of photocopied pages while Times management decided whether to risk publishing highly classified material.

On June 10, word reached Sheehan that, against the advice of Lord, Day & Lord, the paper’s law firm, the Times had decided to go ahead. Editors would use the Pentagon Papers to analyze the war and publish dozens of pages verbatim, with the first selection appearing on Sunday, June 13, 1971. That day's front page carried an article by Sheehan, “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces Three Decades of Growing US Involvement.” It was, the Times announced, part one of a series.

Taking legal action against the Times was not Nixon’s first instinct. In this June 13, 1971, conversation with National Security Advisor Henry A. Kissinger, the president recognized that the Pentagon Papers could help him politically by reminding readers that the Vietnam War was the product of his predecessors’ mistakes. Nixon and Kissinger both assumed, mistakenly, that the release of the study was timed to affect an upcoming vote on the McGovern-Hatfield Amendment, which would require the withdrawal of US forces from Vietnam. To be sure, Nixon denounced the publication as "treasonable," but he decided that the administration should just plow ahead and “clean house” of disloyal people. ("Treason" was the same word that President Lyndon Johnson had used to describe the Nixon campaign's meddling in Vietnamese relations in late 1968. See "Jeff Sessions, the Logan Act, and the Chennault Affair" for more details.)

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript

As promised, Monday, June 14, brought another front-page article by Sheehan: “Vietnam Archive: A Consensus to Bomb Developed before ’64 Election, Study Says.” Nixon’s disposition changed little, and he remained resigned to continued publication. During this conversation with John D. Ehrlichman, who told the president that Attorney General John Mitchell wanted to warn the paper against further publication, Nixon focused on finding out who leaked the Pentagon Papers, not on stopping their publication.

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

Minutes later, Mitchell, who feared that the government would forfeit the right to prosecute the Times if it did not respond immediately, asked Nixon's permission to send the newspaper a warning. Nixon was reluctant to interrupt the airing of the Democrats’ dirty linen, but in this quick phone call he agreed to Mitchell’s plan, reasoning that the Times was an “enemy.”

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

While Nixon was under the impression that the telegram to the Times would be a low-key request for a cessation of publication, the message sent by the Department of Justice was anything but—threatening criminal prosecution under the Espionage Act. The telegram also requested that the Times immediately return the documents to the government. Instead the paper continued to publish, saying it would accept only a court decision.

Even so, on the evening of June 14, Nixon remained relatively unconcerned with what he saw as an unremarkable episode in a troubled relationship with a cantankerous press. According to most accounts, it was Kissinger who was incensed by the leak, fearful that it jeopardized both the United States’ chance to develop closer relations with China and its negotiations with the North Vietnamese. In Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate, however, Miller Center scholar Ken Hughes argues that Nixon was worried the Pentagon Papers leak would be followed by disclosure of his own Vietnam secrets—specifically, the undisclosed bombing of Cambodia, one of his first acts as president, and the Chennault Affair, Nixon’s clandestine effort to forestall peace talks before the 1968 presidential election. (See Hughes discuss his book at the Miller Center.)

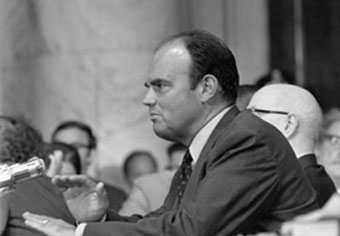

Regardless of the source of his fears, Nixon quickly grew convinced that he was the target of a conspiracy involving Johnson administration officials who had overseen the Pentagon Papers project: Paul C. Warnke, Morton H. Halperin, and Les Gelb, all high officials in the ISA. None of them had participated in the leak. But Halperin had learned about the secret bombing of Cambodia while working in the Nixon White House for Kissinger. And all three had worked as advisors to Defense Secretary Clark M. Clifford during the Johnson administration’s efforts to commence peace talks—so they knew something of the Nixon campaign’s efforts to sabotage them. (This conversation is difficult to understand; follow along using the transcript below.)

President Nixon: This is a very bad situation. This guy is a radical that did it. A radical, we think. Radical left-wing—

H. R. “Bob” Haldeman: [Daniel] Ellsberg? [Unclear.]

President Nixon: [Unclear.] No, we don’t know who the hell he is. But maybe it’s him. Or maybe it’s [former Director of Policy Planning and Arms Control for International Security Affairs Leslie H.] Gelb. One of the two. Either is a radical. So he takes out papers and does it—now goddamn it, [pounding desk] somebody’s got to go to jail on that. Somebody’s got to go to jail for it. That’s all there is to it. Our people here just can’t, however they think about the war, can’t go saying, “Well, we’re doing this and that.” We’ve got to fight it just like hell.

Haldeman: Yeah.

President Nixon: Huh. It really is a tough one. But I think . . . [Attorney General John N.] Mitchell wanted to do it. I said, “Fine. Go.”

---

President Nixon: But, Bob, we’re doing the right—just got—I’m convinced that, you know, the more you think of the situation, I think the more you just have to—you have to fight. The Times thing just really convinced me that we’re up against—I mean, as [National Security Adviser] Henry [Kissinger] said, it’s a conspiracy, Bob. What do you think? Don’t you agree?

Haldeman: It’s absolutely clear. Look at the timing that they put that thing in up there.

President Nixon: [New York Times reporter] Neil Sheehan is a vicious antiwar type. Sure, we’re all against it, but goddamn. And if they’re going to go to this length, we’re going to fight with everything we’ve got. And I—I’m just—I just—we’ll just take some chances.

In public, Nixon wanted to disassociate his administration from what he termed the “Kennedy-Johnson Papers.” Instead he told Charles W. “Chuck” Colson, a White House political operative, to focus on the "larger responsibility to maintain the integrity of government" by keeping secret matters secret. "What the Times has done," says the president in this conversation, "is placed itself above the law."

On June 16, Nixon and Ehrlichman were discussing the legal battle—but only in terms of a larger political strategy to deter all would-be leakers and conspirators. Although the Justice Department was asserting that further publication of the Pentagon Papers represented a threat to national security, In this conversation, Nixon and his aide were more concerned about how a court ruling would affect plans to "launch that grand jury" against Ellsberg.

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

A pivotal meeting took place in the Oval Office the following day. Kissinger distanced himself from Ellsberg, whom he had known personally before their friendship had soured. At an MIT appearance, Ellsberg had repeatedly interrupted Kissinger with questions about Vietnamese casualties that would result from Nixon’s policy of Vietnamization. Kissinger’s anger over the leak seems to have come at least partially from a sense of personal betrayal.

This conversation then escalated into a presidential order to commit burglary. Nixon, Kissinger, and chief of staff H. R. "Bob" Haldeman discussed getting former President Johnson to speak out against the leak, and Haldeman suggested blackmailing LBJ. The trio then reviewed a report from aide Tom Huston suggesting that Gelb had a copy of undisclosed reports on Vietnam stored in a safe at the Brookings Institution. Huston was the author of the "Huston Plan," a secret proposal to expand the use of government break-ins, wiretaps, and mail opening in the name of fighting domestic terror. Nixon told his aides to implement the Huston Plan and steal the Vietnam documents from Brookings. It would not be the last time he would suggest breaking the law.

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

Despite his anger with Johnson, Nixon’s interest in waging a public opinion war was already fading five days into the Pentagon Papers controversy. His interest in a covert struggle against his enemies, however, was on the rise. By the time the Supreme Court agreed on June 25 to hear United States v. New York Times Co. (403 U.S. 713 [1971]), several other papers had joined the Times in publishing portions of the Pentagon Papers, including a codefendant in the Supreme Court case: the Washington Post.

This conversation with Attorney General Mitchell also reveals the president's frustration with J. Edgar Hoover. As director of the FBI, Hoover was in charge of the official investigation into Ellsberg. But Hoover was also friends with Ellsberg’s father-in-law, Louis Marx. Nixon asked Mitchell to lean on Hoover, and then began to wonder if the White House would have to investigate the matter itself.

Just as his previous conversations reveal significant political motivations for legal action against the Times, Nixon focused on Ellsberg to strike fear into the hearts of would-be conspirators and stem the flow of potential leaks from enemies inside the government. Nixon remained dissatisfied with Hoover’s investigation and took steps to launch a parallel investigation of his own.

The next day, by a vote of six to three, the Supreme Court ruled that “the government had not met the ‘heavy burden’ of showing justification for a prior restraint.” In other words, the Times and the Post, as well as other newspapers, could resume publication of the Pentagon Papers. Believing the court case no longer mattered, Nixon’s initial reaction was to remark on the distribution of votes, not the outcome. Once again, he explained to Colson that nothing, not even the Court’s ruling, would stand in the way of his putting Ellsberg in jail.

Now Nixon focused on attacking Ellsberg, concluding that the White House would have to do its own investigation using any means necessary. His instincts for self-preservation engaged, Nixon rationalized this course of action in this conversation with Haldeman on the night of June 30, saying, “It’s a tough game.”

The leak of the Pentagon Papers brought forth a profound paranoia in Richard Nixon, hardening his conviction that he would never be safe from a vast conspiracy seeking to destroy him. The president's reaction led his administration to institutionalize a systematic effort to attack those he deemed enemies and to seek out and destroy threats, especially from leakers. The ultimate manifestation of this drive was the White House Special Investigations Unit, informally referred to as the Plumbers, whose first assignment was to raid the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist. Later, members of the group carried out one final mission, the Watergate break-in, which ultimately cost Nixon the very thing he had sought to defend: his presidency.

There’s an absolutely clear line, if it hadn’t been for the Pentagon Papers, maybe Watergate would have occurred later, maybe it would have been different, but the abuses would not have been so great.

Sanford Ungar, author of "The Papers & The Papers: An Account of the Legal and Political Battle over the Pentagon Papers"

Jordan Moran is a former research intern with the Presidential Recordings Program. Special thanks to Ken Hughes for his assistance with this material.