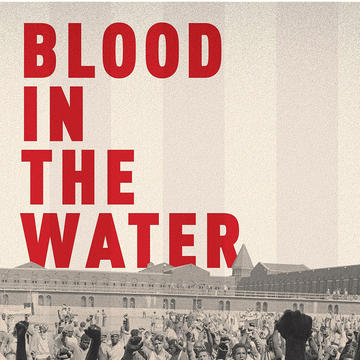

'Kill a few'

Nixon's cold-blooded take on Kent State showed little regard for those opposed to him

President Nixon and his chief of staff, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, had just finished discussing which governors they could expect to attend a land transfer event—a more anodyne topic one could hardly imagine—when the conversation returned to the uprising at Attica Correctional Facility in New York.

Inmates had taken violent control of the prison and for five days had been negotiating with state officials, including Governor Nelson Rockefeller, to address overcrowding and other issues. But on September 13, 1971, after refusing to grant amnesty for illegal actions during the uprising, which included taking guards as hostages, Rockefeller decided to end the standoff. The New York State Police moved in to retake the facility with ruthless brutality. An hour later, 29 prisoners and nine hostages were dead.

You know what stops them? Kill a few.

The president’s response: “This might have one hell of a salutary effect. They can talk all they want about the radicals. You know what stops them? Kill a few.

“Remember Kent State?” the president continues. “Didn’t it have one hell of an effect, the Kent State thing?”

“Sure did,” replies Haldeman. “Gave them second thoughts.”

Footage from CBS News on the Kent State shooting, May 4, 1970

The Miller Center’s Ken Hughes uncovered the chilling conversation in response to a request from journalist and author Bob Woodward, who was visiting Kent State and asked Hughes for some relevant audio. Although the tapes are in the public domain, many historians shy away from them in favor of more accessible written documents. But for understanding the Nixon presidency, there is no substitute for the unvarnished look they offer of the man, his presidency, and the era.

The Miller Center’s Presidential Recordings Program continues to review and publish the Nixon tapes—and those of other presidencies—to offer citizens, policymakers, scholars, and students historical perspective on the inner workings of American democracy. Hughes is among the nation’s foremost experts on Nixon, Vietnam, and Watergate, but he’d never heard of the recording before.

“My first reaction was that Woodward could probably use this in his presentation,” says Hughes. “But it was a surprise to me that Nixon saw the Kent State massacre as somehow intimidating the demonstrators. . . . And I don’t think that necessarily was proven by responses after the shooting.

“Nixon did not see protest against the Vietnam War as a reflection of legitimate moral opposition to a war that could not be won and should not have been waged. He saw it as rebellion, and particularly, he personalized it. He thought that the Democrats were against the war because they did not want Nixon to win it—which is an odd thing to believe, since he himself realized he could not win it.”

What emerges from Nixon and Haldeman’s discussion of the prison uprising isn’t as straightforward as it may seem at first. Certainly, the unemotional nature of Nixon’s remarks and his talk of toughness are familiar to Nixon scholars. “He prided himself on analyzing things in a cold-blooded fashion,” says Hughes, “not looking at the human implications of events but the political and sometimes geo-political implications of them.”

Is this a black business?

The Attica discussion, even before the Kent State comparison that concludes it, highlights a president who saw complex issues of race, social protest, and criminal justice through a lens of social and political power: There were groups trying to undermine the nation and his presidency, and he was determined to stop them. In this context, the individual lives of Attica inmates or Kent State protesters were of lesser importance.

Earlier in the day, after Haldeman informed Nixon of the police raid to retake the prison, the president asks, “Is this a black business?”

“Yes sir,” replies the chief of staff.

“We have got to be tough on this,” Nixon says. “You know what this is? This is the Angela Davis crowd,” adding a few seconds later, “these are the negroes.”

“Which concerns me,” adds Haldeman. “The word is around now that this is the signal for the black uprising.”

“It’s clear this is what they’re doing,” the chief of staff goes on. “The revolution thing is moving to the prisons now, versus the campuses where they couldn’t get enough action on.”

Later, Nixon calls Rockefeller, who calls the raid “a beautiful operation,” to congratulate him. “Tell me, is this a—are these primarily blacks that you’re dealing with?” asks Nixon.

“Oh yes,” responds Rockefeller, “the whole thing was led by the blacks.”

After the congratulatory call, Haldeman asks, “Were they all black?”

“Every one,” responds Nixon.

Seconds later, after conceding, “They’ve probably got some legitimate grievances—I’m sure they do,” Haldeman reverses course, “My guess is, looking at it, that it has nothing to do with anything legitimate; it has to do with the revolution.”

We’ve got to be tough.

“This whole business of permissiveness on campus,” concludes Nixon, tying the moment back to his larger themes, “why not permissiveness in prison, permissiveness to the blacks? It’s not—we’re not going to turn around here in this town. If they hit this town again [i.e. come to Washington to protest], we’ve got to be tough.”

The toughness Nixon was so keen to display would make another significant appearance on the Oval Office recordings of his presidency. Agreeing to a plan to use the CIA to thwart an FBI investigation of the Watergate break-in less than one year later, Nixon would tell Haldeman to, “Play it tough. That’s the way they play it, and that’s the way we are going to play it.” The recording would come to be known as the Smoking Gun.