Transcript

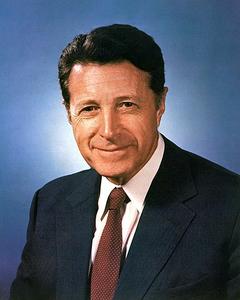

Weinberger

I have two points at the outset: 1. You mention the Pentagon’s

mismanagement.

I do not know what that refers to; 2. You mention somereluctance

toinvolve American troops.

Only when you need to spell out the situations in which they’re required to be used, in which case there’s no reluctance, but no particular eagerness, either.Knott

I see.

Weinberger

I think the way the phrasing is that at that time, having responsibility for the care and safety of the troops, I was somewhat more cautious than people who didn’t have that responsibility, or had not had the experience that I happened to have had. So it was not a reluctance. It was just a matter of spelling out the times when it would have been essential for them to be used, and then to use them in overwhelming numbers so that they would win—all of which was considered revolutionary at the time. Okay, now it’s your turn.

Knott

Thank you very much for joining us. This is an interview for the Ronald Reagan Oral History project with Caspar Weinberger, and we’re delighted that you’re with us today. We’ve all introduced ourselves, and we’ve talked a little bit about—

Weinberger

At my age I’m delighted to be anywhere.

Knott

I thought we could start off by simply asking you when you first met President Reagan and what your initial impressions of him were.

Weinberger

I met President Reagan the first time when he was being talked about as possibly running for Governor. He was very prominent. He was already a celebrity, and he came up to San Francisco from Los Angeles for some political meeting, the general purpose of which was to introduce him to political people in the north whom it was supposed he did not know very well. He came up to—I think it was the old Sir Francis Drake or St. Francis Hotel. He came in and was generally introduced around. I put in the autobiography that his enormous magnetism showed almost immediately. People flocked around him. Californians love celebrities, and he was a certified celebrity, having been in the movies, which was a double dividend for Californians. He stood out immediately in the crowd and had an enormous amount of charm and excited a great deal of almost immediate support just by being there.

At that time, George Christopher was the only announced candidate, and President Reagan was there not necessarily to oppose Christopher or even enter the race, but just to be introduced to a lot of people who had heard of him but had never actually met him. That was two years or so before he ran, maybe a year and a half.

Knott

You were very active in California politics in a number of different capacities, and he asked you to serve in his cabinet as the Director of Finance, do I have that correct?

Weinberger

Yes.

Knott

Could you just talk a little bit about his governing style as Governor of California?

Weinberger

Governor of California. Well, he was the first to admit that he was not familiar with a great many of the details of state government or its responsibilities—jurisdiction and all. He was very humble about it and said he needed all the help he could get. Prior to his election—after he won the nomination, but before he was actually elected—we had various transition and taskforces working with Bill Clark and with me to recommend governmental structures—organizations for running the government and things like that. He was briefed many times on that. He was a very, very quick study and had an absolutely photographic memory, which he always said was part of his heritage as an actor.

He was very easy to work with, to talk with, and wanted to get the various necessary details. He knew what he wanted to accomplish, and he wanted to know how to do that and how to go about it. Once he was satisfied with the basic procedures that he would have to follow and what would have to be done, he went ahead and did it. He never worried about the political effects or anything of that kind.

Knott

You say he had a photographic memory—

Weinberger

Yes, photographic memory, absolutely. That’s one of the most difficult things to realize now that his memory is completely gone with this terrible disease. We used to brief him before press conferences. Three or four people would brief him. Obviously, the rule was to think up as many difficult, disconcerting, and hostile questions as we could to see what sort of responses he would make. If he said he didn’t know anything about that, we would talk a little bit about the subject matter. He would get it into his memory, and then he would go out. Most of these questions would come up in the press conference, and he was just absolute—photographic. He could repeat proposed answers, almost word for word.

He had a very interesting habit of occasionally giving totally wrong and completely wild answers just as a sort of joke from time to time in the rehearsal meetings. It was quite hilarious, but I was always extremely worried that he would tack one of these on to a real answer. However, he never did. But he enjoyed himself. He liked the give and take, he liked meeting with people. I think he even enjoyed the press conferences. He was very, very good at it. The general comment at the end of the press conference was most reporters going out saying,

We never laid a glove on him.

Riley

Were you surprised, as somebody who had extensive experience in politics, at how well he adapted to the political arena?

Weinberger

Oh yes, yes. People kept saying,

Well he’s an actor, he’s playing a role.

Not really at all. He had great flexibility, and when the questions moved away from the rehearsed questions or even into more detail, he was always ready. People talk about him being the great communicator. He had an enormous ability to articulate what a very large number of men and women felt and thought and didn’t articulate very well themselves. He always spoke for them. He had a great desire to do that. He had a great desire to get along with people. He always said he liked to leave them laughing.He had a unique speaking capability, and that was, he could talk to an audience of three or four, or he could talk to an audience of 10,000 people. Yet you always felt that he was talking right at you, that you were the one he wanted to talk to. It was amazing, because even in these huge auditoriums, you had this feeling that he was talking to you.

Knott

Were there any aspects of the political life that you noticed that he did not enjoy or maybe had some difficulty with?

Weinberger

I don’t know that he really did. He never avoided any difficult confrontations. He used to love to go on university campuses—where he was very hostilely received at first. He never wanted to use a back entrance or anything. That always infuriated him, that sort of suggestion. He’d walk right through the crowd, even if they were quite clearly hostile at the beginning. He really had an enormous ability to bring people around to his viewpoint, and he enjoyed doing it. They used to say about him that he could charm anybody, but for people who really hated him it took ten minutes.

Knott

Could you tell us a little bit about any involvement you had in the 1980 campaign itself?

Weinberger

The 1980?

Knott

The presidential campaign.

Weinberger

At that time I had been Director of Finance for some time. I had been in various state committee offices. I did not hold any state office at that time. I was out of the legislature, and I was a delegate to the convention in Detroit that nominated him. We talked quite a bit before the nomination, always with four, five, or six people who were close to him, always Bill Clark, and occasionally Mike Deaver and people who had been with him a long time.

At the convention we pretty clearly had the majority of the delegates, but nothing was ever very firm. There were a lot of people who were supporting Vice President [George H. W.] Bush, who had been in the primaries, too. He had what we believed was a lead, but you never really knew until the actual votes were taken. There were a number of people who realized that he had a lead, and who were horrified at the idea that he might be the nominee. Various stratagems were being proposed, including one that would have had former President [Gerald] Ford be his running mate—Vice President—but that the line of demarcation would be set. President Ford would have five or six of the Cabinet to appoint himself, even though he was Vice President, and he would be in charge of most of the major domestic departments. He would have a major role in foreign policy and all of that. This was to be an arrangement that provided what they all called the

dream ticket.

President Reagan didn’t comment on it at all while these proposals were being made and various emissaries were coming to his suite and presenting various bits and pieces of it. Finally, after everybody had cleared out and three or four of us were left, he turned to me and said,

What do you think about this?

I said,Well the trouble with it is

—I always called him Governor—The trouble with it, Governor, is that it’s basically unconstitutional.

He said,Why?

I said,The Constitution doesn’t have any provision whatever for the President delegating duties of that kind. The President is the President, and the Vice President has very specific, narrowly limited duties, and there’s no way in which you could delegate to anybody the right to appoint a Cabinet officer or turn over the management of a portion of the government to anyone else.

He nodded to himself. Meanwhile, an enormous amount of leakage had gone on that this was a done deal. This was in the afternoon, and it was all supposed to be taken to the floor that evening. It became apparent that this simply wasn’t going to happen as the afternoon wore on. In one of the final meetings in his suite—after we talked about the constitutionality of it, and the basic impossibility of it—some people started to make some arguments about it. He sort of waved them off, and he said to someone—I think probably Deaver—he said,

Get me George Bush.

So he got George Bush on the phone and offered him the Vice Presidency without any of this going through former President Ford or anything of the kind. He said,

Bush is the man closest to me, and he’s the one we’ve run against, and we have the votes, and I want him as my Vice President.

Vice President Bush accepted, and that was it.Then the press went wild. They kept coming up to me with the question,

What went wrong?

What happened?

Wasn’t it all settled?

I said,It was only all settled in your rumors. It was never settled by the man who was the most involved.

They simply couldn’t believe it. They thought something unknown to them had happened that changed it all. They just assumed that because these rumors were there, it was the fact, and it never was the fact. So he was very decisive and very firm on that and worked very well with Vice President Bush. It would have been a totally impossible arrangement to put former President Ford in as Vice President with a lot of previously settled division of the power.Riley

Had you been a supporter of President Reagan in 1976 when he was considering a presidential run? He was challenging Gerald Ford at the time.

Weinberger

No. I was not active in it at that time. I think I was even out of the state party activity at that time. I generally thought that an incumbent President was entitled to be re-nominated, and President Reagan’s running at that time was very uncertain and almost half-hearted. He didn’t really want to do it. He got into it only at the very end, at the convention, when the votes were all settled. There was no question whatever that President Ford was going to be re-nominated. I think I was probably pretty passive in that campaign mostly because I was devoting full time to my new post at Bechtel.

When he first ran for Governor, I had previously signed up for George Christopher, who was Mayor of San Francisco and whom I’d known for years and who had supported me in my first campaign for the legislature. When President Reagan decided that he was actually going to run for Governor, I told him and told all of the people around him that I had committed to Christopher, and neither he nor I would want me to give up a commitment of that kind. After he was nominated, I joined with him at his request, and then worked with the transition teams devising the various governmental structures that he would later adopt when he became Governor.

Knott

Back to 1980, Governor Reagan wins the election. Could you tell us the role that you played during the transition period and how you came to be selected as Secretary of Defense?

Weinberger

I don’t know how, that was up to him. He had a group of people called his

kitchen cabinet

in Los Angeles, which used to meet in Bill French Smith’s law offices in Los Angeles. We went down several times and went over long lists of names for various positions, names that had emerged from various quarters and suggestions, and there were overlaps on it. I guess I was on three or four lists, first to be OMB [Office of Management and Budget] Director again—which I didn’t want to do, having done that—and State and Defense and Treasury. As each of these offices was considered, anybody in the room who was on the list would get up and go out while they considered them in their absence. So I was always going out—Ultimately they gave him three or four names for each office that they all recommended and that they thought would be very good. There were a number of people in these meetings, and they all were making recommendations. It was basically informal, but they were people he’d worked with for a long time before he became Governor, and who had been very active in his presidential campaign, as I was. So we had these recommended lists that went to him. This was all in roughly October, when it became apparent that he was probably going to win—November, December.

I made a couple of trips to Europe. I was with Bechtel at that time and had made a couple of trips to Europe and stopped off, particularly in England and a couple of other places. There was complete horror at the fact that this

actor

might be President of the United States, and total disbelief in the fact that only in America, only in California, etc., things like that could happen. I thought it was important to tell them that they were quite wrong, that they were working on stereotypes, and they’d never met him, and they would be completely surprised—pleasantly—at his ability to do the job.Ultimately various names went to him, and he then made his own selections. He notified me on December 1—which I remember because it was my father’s birthday—that he wanted me to be Secretary of Defense. He started out by saying,

I know you have a very full and a very rich and a very satisfying and a happy life.

And he said,I want to spoil the whole thing.

Then he offered me that, and I told him I would obviously have to discuss it with the family but most anything he wanted me to do I would be glad to try to do to help him because I believed very strongly in what he stood for and wanted his Presidency to be a success. So we ultimately concluded that I would indeed do it.Riley

Do you have some sense about why he wanted you in the Defense—

Weinberger

No, we never went into that in any detail. He said that he liked the work I’d done as finance director, which had been a different kind of assignment. When I was finance director we had a very large deficit—which you’re not permitted under state law. You have to balance the budget in California, by constitution. It meant you wouldn’t be able, in time, to make the kinds of cuts that were necessary, so you would have to increase revenue. He was very unhappy with it, but he accepted it because he knew it was a constitutional duty.

I had suggested various ways in which we could make reductions. When the tax revenues started producing, the economy turned around quite quickly, and I saw we were actually going to have a surplus. I went around to him and told him that we would have a surplus and that the legislature would want to have all kinds of projects now, having had cuts before. I thought he ought to know about it first and decide what he wanted to do with it. He said,

Let’s give it back. Can you do that?

I said,Well, yes, of course you can do it. But nobody’s ever done it before.

He said,You’ve never had an actor for Governor before.

So we worked out a tax reduction plan, a tax restoration so to speak, and everybody got a percentage back from the taxes they had to pay, and the economy boomed as a result. He had a lot of these ideas of his own, and he knew what he wanted to accomplish, and he mostly just wanted to know how to do it.

Knott

Can you tell us what your priorities were as Secretary of Defense?

Weinberger

As Secretary of Defense it was very clear. We had campaigned on the fact that we had had inadequate resources for defense and that we were falling behind a steady Soviet buildup, and that we needed to restore our deterrent capability. After he was elected, before he took office, we were given formal classified briefings, and saw it was infinitely worse than we had thought. The Soviet expansion had been taking place at a very rapid rate, and they were actually ahead of us in practically every category—planes and submarines and surface vessels, artillery pieces, infantry division, and small arms, everything. The gap was growing because we had been taking the basic idea of détente very seriously and had cut back. They took the idea of détente seriously and expanded. So the gap was growing.

We never had in mind the idea of matching them tank for tank or heavy artillery piece for heavy artillery piece, but we had in mind the idea of restoring a capability that would convince them that they couldn’t win a war against us. This involved restoring a very substantial amount of military capability very quickly—which is the worst way to do it, most expensive way—and it also meant repairing our alliances. We had a lot of holdovers from the [Jimmy] Carter years, during which we had talked very grandiloquently about good intentions of everybody and the infinite perfectibility of human nature and things of that kind—meanwhile watched Afghanistan be invaded by the Soviets. We never had any response to the Afghan invasion by the Soviets except to tell them we weren’t going to play in their Olympic games. That was all that we could do at that time.

The President was very anxious that we get our capability back, and during some of the transition meetings that were held in the State Department after he was elected, before he was inaugurated, two or three people suggested that one of the real dangers was Cuba, and another one was Poland. The Soviets had kept two divisions in Poland, after the war—they were still there—but they were also massing a very large number of other divisions on the border because they were very unhappy with the suggestions of revolt, so to speak, within Poland and the Solidarity Movement and Lech Walesa. It was quite apparent that the Soviets, within a short time, had a perfect capability of simply pouring into the country and throttling anything of that kind. A lot of people wanted to pre-empt that and talked to him about that at some of these meetings.

On the way out I said,

You know, Mr. President, that probably would be the best thing to do, but we simply can’t do it now. We have no military capability of going over and putting any kind of force in to protect Poland.

He said,I know that, and we must never again be in this position, Cap. That’s what we must do first.

That was essentially what he campaigned on, except that the actual requirements were much worse when we found out, in office, how big the gap was.Knott

Another priority of the President’s initially was to try to balance the budget. Of course, the growth in defense spending became an issue, and there were some reported conflicts between you and David Stockman—

Weinberger

They were actual. But again, there was no way of balancing the budget. The Federal budget had a very big deficit to start with. What was important was to get this military capability back, and he knew that. He had said frequently in the campaign—in fact, one speech I was present at, outside of Detroit—oddly enough, in a Polish suburb of Detroit—Hamtramck—where there was a very large amount of automobile manufacturing—he said,

If it ever comes down to a question of balancing the budget and getting rid of the deficit, or regaining our military capability, I’m always going to come down on the side of the military, because they’ll have to have it and they have to have it quickly.

So we took that as a given. The other thing very few people remember or even talk about is that President Reagan submitted eight budgets during his eight years. Every one of those budgets would have been very, very close to balanced if the Congress had ever enacted the cuts. But they never did, and he allowed himself to be talked into—by a couple of advisors, who I thought gave very unfortunate advice—by agreeing that he would accept a tax increase if for every dollar tax increase there were two dollars of cuts made, some kind of complicated thing like that. The Democrats were delighted, and they seized on that immediately. They grabbed the tax increases, and they turned down the cuts. He didn’t get fooled with that kind of advice again.

The deficit did go up, but it wasn’t entirely due to the defense spending. A lot of it was because the Congress had refused to make the cuts that would have brought the balance much closer. He also, I think, became convinced that contrary to the conventional wisdom, deficits weren’t necessarily lethal or fatal, and that it was possible to deal with them. Although he didn’t like the size of them, and he didn’t like the fact that there were no corresponding cuts. His ideal budget was one in which the defense would have been increased and other departments would have been cut. As a result, there was a very great deal of opposition, within his own Cabinet, to virtually everything we tried to do.

Riley

You mentioned when you were serving as budget director in California—you didn’t say it this way—but almost out of thin air, a significant deficit was converted into a surplus. Do you think that experience might have impressed on him some notion that forecasts are not—

Weinberger

Yes. There was one absolute constant about all governmental economic forecasts: they were always wrong. There’s no way in which they could have been right. You’re talking about four or five years out, three or four years out. There are too many factors—I mean, California particularly, where they were heavily dependent on the sales tax, which in turn depended on the national economy—how much people were buying. If people cut back their buying, the sales tax revenues went down and the deficit increased.

But he never wavered. He had a lot of people who were very strongly worried about the amount that was going into defense—the Commerce Secretary and other people—who were friends of mine or had been!—all felt that this was very wrong, that we should be counseling him to cut back on the defense, or take it very slowly. He and I, I think, were convinced that we couldn’t take it slowly. We didn’t have that option, because this gap was continuing to grow.

I frequently pointed out to the committees, as well as to the President, that when we want to increase the defense budget, it was an enormously difficult job because people in democracies don’t like to spend money on defense. This has been remarked on by everybody since [Alexis] de Tocqueville, who said it’s going to be hard for democracies to remain democracies unless they overcome this reluctance to finance defense. The President knew that we would have to do far more than he would like to do—or I would—at the beginning to try to redress this balance.

Riley

Can you tell us how you managed as Secretary this enormous influx of money.

Weinberger

Well, it didn’t come all at once. There were very long lists of things that all of the services wanted, and what isn’t understood is that we had to cut that back. A lot of people thought we just granted their requests automatically. We got a big increase—which we had to have—but we had then to allocate it to the various priorities. We had several priorities including two or three things—we had, for example, such very basic things as the so-called readiness accounts—ammunition, fuel for training air and naval units, to increase the amount of purchases of weapons that we had. I always insisted on putting quite a lot aside, comparatively speaking, for research and development, because we needed to keep doing that. Some of the fruits of that paid off in the Gulf War many years later, because we had these very smart weapons which enabled us to win the Gulf War with very little cost to ourselves.

And we had a new tank that had been on the drawing boards for something like fifteen years. It was constantly being revised, and it was the old story about how the desire for perfection completely destroyed the ability to get anything done. Every time you’d get it about ready for production, they’d want this added or that subtracted, and so we decided to cut that process and stop it right there.

We had the bombers—the B-1, which Carter had canceled after an enormous amount of investment had gone into it. And we were working very clandestinely on the Stealth mechanisms, the B-2, and the Stealth fighters, and even some Stealth characteristics for some of the naval vessels, which took a lot of money and had to be done all in so-called

black programs

in secrecy. Defense committees in the Congress used to ask me,What is your highest priory?

The trouble was I had several priorities.Basically, one of the very first things was restoring morale, because the all-volunteer system was not working. People were not volunteering. People were leaving the military in droves. Many of the enlisted personnel were on food stamps trying to supplement a very, very low income, and leaving the military to get other jobs. So we really had to start with that. You quite literally did have a number of different priorities, and you couldn’t do just one thing at a time. You had to have all these different balls in the air at one time.

Knott

There’s been quite a bit of commentary written that President Reagan had a vision of toppling the Soviet Union, and it involved various—economic pressure, covert campaigns, the defense build up. Could you comment on this?

Weinberger

Well, there were some people who said that the whole thing was just an attempt to run the Soviet Union into bankruptcy. Actually it was not, in my view. What he needed, what we needed—and we were in full agreement on it—was to restore our military deterrent capability—to get a capability that would make it quite clear to the Soviets that they couldn’t win a war against us—in such black and white terms as that. This required regaining a great deal of military capability very quickly. It also required repairing our alliances—the NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] alliance and a lot of the countries that had felt we were quite unreliable allies, particularly after Afghanistan, when it was quite apparent that we couldn’t and weren’t going to do anything, and particularly when we kept talking with a lot of these countries, which were basically under the thumb of the Soviet Union and trying to get them to be more friendly to the West. The Soviet Union simply didn’t permit it. The Warsaw Pact countries were not allowed to trade, and all the rest of it, except with the Soviet Union—and on very unfavorable terms to those countries.

While we knew that there was a great deal of unhappiness and dissent within those countries, we didn’t think—I didn’t think—that anybody could ever do anything about it, for a very simple reason: The Soviets had all the guns. There was no way in which these people could get any kind of effective revolt going without simply committing suicide, and that’s essentially what was being threatened in Poland and happened in many of the Baltic countries and others.

We had, at the same time, this very strong so-called

Peace Movement,

and détente, and a number of theories of containment, and the idea that these were just two different systems, that they can live with each other, they’re compatible, and all that. President Reagan repeatedly said that simply is not so. There is no compatibility, and you can’t live with a system whose goal is to destroy freedom and to deny people all of the things that we have and take for granted.It was very apparent to him that the cold war was a lot more than containment and a lot more than keeping the status quo. Indeed—it’s been written about many times—before the so-called

Evil Empire

speech, he had concluded that the cold war had to be won, that it couldn’t just be dragged on as a stalemate in which we accepted the fact that the Soviets were always going to be there, and they would have the East, and the West would try to hold the West. He said,No, we’ve got to win the cold war.

When he was going to make that speech about the evil empire—in London, I think it was, at the House of Lords—he had several drafts prepared, and in each one he put in that this was an evil empire, that it had to be destroyed, and that phrase was always taken out.The third time he didn’t put it in the draft, but he gave the speech with that phrase. And you could hear this gasp from the conventional wisdom people virtually all over the world. Someone came to him and said,

You’ve destroyed twenty years of patient diplomatic effort.

And he said,But what did patient diplomatic effort for twenty years get us? It got us an expanding Soviet Union and a continual expansion of their ability to enslave peoples and deny freedom. And it left us so vulnerable we couldn’t do anything when Afghanistan was invaded. That’s not much of an accomplishment.

So from there on in, the cold war had focus, and we did win it.Riley

When you first became Secretary of Defense, you didn’t have a great deal of experience—

Weinberger

Well, that’s a very diplomatic way to phrase it. Most people say I didn’t know a damn thing about it.

Riley

If we take what most people say, did you go about a process of self-education? You seem to be somebody—

Weinberger

Indeed I did. Yes.

Riley

Can you tell us a little bit about how one educates oneself?

Weinberger

I quite simply absorbed everything I could about defense and security matters and did virtually nothing else. But of course, there isn’t anything else—it’s full time. You’re never on vacation, you’re never on leave, you’re always on duty. Twenty-four hours means twenty-four hours, including anything that would go wrong in Libya or [Muammar] Gaddafi challenging our right to free navigation in the Gulf of Sidra, and all kinds of things of that kind—more or less small crises—were constantly going on. At the same time, we had this huge fight with Congress about expanding the budget, and I had to learn as much as I could as quickly as I could. I treated it roughly like a huge law suit and trial that I would have to conduct and simply immersed myself in it completely.

Riley

Did you talk with former Secretaries of Defense?

Weinberger

Oh yes, yes, I did. But what we were doing was so new and so different that you didn’t get much more than warnings from them.

Riley

You’re reputed to be quite a student of [Winston] Churchill. Was there something in particular about Churchill’s writings that you found useful?

Weinberger

Yes, of course. It was quite an example that he set. Oh yes, I was. He had encountered very much the same kind of thing during the appeasement years, and had the same set of difficulties in a democracy in getting people interested in following what are basically difficult courses. It’s typical to talk about how he was an

uncomfortable hero.

He was always urging very uncomfortable courses of action, and it was lucky that he did. He had barely time to do it.I was obsessed by the shortness of time, because we had fallen far behind, and we were not—without very drastic measures, increases and so on, which were very hard to get—going to be able to make any kind of balancing out of our own defensive capabilities. I knew that we had a comparatively short time to do it, because the tolerance of the Congress for increasing defense spending was wearing thin the first month, and it kept wearing thinner and thinner as we went on. We were able to maintain a major increase in defense spending and capabilities for over four years. After that the reaction set in. I used to be told,

You came up here last year warning about all this, Mr. Secretary, and nothing happened, so why do we need to do it again?

It was roughly the question ofYou didn’t have a fire, so why do you need fire insurance?

Knott

In those first years in office, one of the most critical decisions that you and the President faced was placing the Pershing IIs in western Europe. Could you talk a little bit about that episode and the nuclear freeze movement that was gaining steam at this time?

Weinberger

This was not a side show, but was a separate sort of issue. I went to all the NATO meetings, because I thought it was very important to repair the NATO alliance. We had bred a lot of distrust of us as a result of our actions in previous years—in the Carter years, which seemed to be more or less years of appeasement, or attempts at it, while our whole military capability was running down. The NATO alliance was there. It was the most important alliance we had, yet it was not in very good shape because they didn’t regard us as a very reliable ally. Quite naturally, in very human terms, they wanted to be on the winning side.

They also knew the capability of the Soviets to overrun Europe was there, and while obviously they didn’t favor that, they weren’t all that strong for anybody who was talking in confrontational terms. That’s why détente was so popular, and why it was so unpopular to put in any kind of response to the SS-18s or to the Soviet missiles. The Soviets had put in a whole new family of missiles that were capable of hitting any target in Europe and most targets in Asia, and yet he had no response capability, none whatever. That’s what the Pershing and the ground-launch cruise missiles were supposed to do. Finally they got a resolution through NATO to the effect that we’d go on a two-track system. We’d worked very hard for agreement and negotiations to get some of the Soviet missiles removed, and at the same time we would station some of our missiles in Germany and Belgium and Italy and England.

Of course, that was challenged every meeting. There were people who wanted to get away from the two-track thing, and any time you’d talk about putting our missiles in, that was provocative, and caused huge demonstrations at most of the NATO defense ministers’ meetings. One or two in Bonn were just gigantic demonstrations against any kind of effort to do that. I was sort of the focus of all of those, and in England too, where there was huge opposition to deploying these missiles in those countries. People would say to me,

You don’t know what it’s like to be right near, as a target.

I’d say,On the contrary, the principal target of all of the Soviet missiles—the number one target—is the center court at the Pentagon

—which it was. They’d blast out all the communications and everything else. I had a very good idea what it was to live near a target, and indeed to be the bull’s eye. Each NATO meeting was a big struggle, but we did manage to hold that so-called two-track system. But that required negotiation, and the negotiations that we had conducted first involved the so-calledzero option,

which President Reagan liked.That was the idea:

You take all yours out. We won’t put any of ours in, and then the balance will be restored.

The arms control advocates were purple about that because they said that this was a ploy.You know the Soviets will never agree to it. You’ve got to have a proposal that you know they’ll agree to.

That had been the basis for the so-called START [Strategic Arms Reduction Talks] talks, the strategic arms reduction. The only problem was those agreements didn’t reduce anything. They allowed for a smaller increase than had otherwise been planned, and President Reagan thought that that was a pretty useless kind of agreement. We submitted this instead, and, indeed, the Soviets said they would walk out if we deployed anything at all, and they would never agree to that.This was in October of ’81, I guess it was. Then in November of ’87 they did agree to it, without any conditions or anything else. It was the icing, solely the result of the fact that, first of all, they didn’t believe we would do it, and secondly, that we couldn’t get European permission to do it. When we finally got the Belgium approval, we were in England and meeting all kind of oppositions and demonstrations, and Italy had very strong opposition and yet they put them there too, despite demonstrations. But when Belgium and Holland agreed, finally, on a very late night vote in their Parliament that we could deploy, we had been loading the missiles all the week before, and as soon as the gavel came down, the planes took off, literally. So they were there the next morning, and this was a source of not only great surprise but great unhappiness to people who thought they could reverse these very close Parliamentary decisions.

When all of that was done, and the Soviets saw that the alliance was holding firm, that we were regaining a vast amount of military capability, and were even talking about the strategic defense measures which would have rendered impotent a large part of their offensive capability, they came around.

Knott

You did something very unusual, there’s a picture on the wall here—

Weinberger

Oh, that’s the Oxford debate.

Knott

That was a somewhat out of the ordinary act for a Secretary of Defense.

Weinberger

You see I’m in black tie, and the man opposite me here was [Edward Palmer] Thompson, who was a Marxist professor by his own statement, and the topic of the debate was,

Resolved, there is no moral difference between the foreign policy of the U.S. and the USSR.

He spoke to that. There was a huge crowd there—it’s modeled on the House of Commons procedures—and I was told many times that it was a very foolish thing to do. Our embassy urged me very strongly not to do it. But I had told the students that I would do it, so I went ahead with it. They saidYou’ll never win it, and it will be a very great story, comparable to the one before World War I, II, and all the rest of it.

But we went ahead with it. They divide—like the House of Commons, the ayes go out into the aye lobby and the nays to the left, ayes to the right, nays to the left. And ultimately we won by—I don’t know—20, 40 votes or something. It was a very big debate, and it diverted attention for a bit. The fact that we won was noted here in the U.S. I don’t know how it was explained in Europe. But Thompson was very distressed about it. He would not wear black tie—he said it was an emblem of class, and he wasn’t going to do that. I told him the story of my father who had said that black tie is the most democratic costume there is because everybody wears exactly the same thing, which amused the students. You can see the students were not in black tie. That was a silly thing to do, really, in retrospect. To require black ties and the student officers in white tie.

Riley

Just out of curiosity, how did the invitation come to you?

Weinberger

It came to me from the head of the union, who is right up there presiding and who is also a Marxist. He and Professor Thompson were both members of the Communist Party and perfectly willing to admit it and defend it. I suppose they thought it would be an interesting bear-baiting or something. But one way or another, I had agreed to do it primarily because I’d heard of the Oxford Union for years and years and was anxious to see it.

Knott

And you had a strong relationship with Prime Minister [Margaret] Thatcher?

Weinberger

Well, she is a remarkable lady in every way and also was very much the same as President Reagan in being willing to challenge—and challenge very successfully and very effectively—the conventional wisdom. She and President Reagan, I think, had more to do with changing the political agenda than anyone else. They supported things that people didn’t even talk about because they were so far off the conventional screen: small government, cutting taxes, privatizing services, decreasing the power of the government to increase the power of people, and so forth. All of the standard things that we now take for granted and debate very vigorously.

It’s hard to realize or recall, but in the years they were coming to power, these things weren’t talked about. These were not issues at all. This was several years ago. It was not a question of whether you wanted big government, it was just how big a government and how would they do it? You turned to government to solve any particularly difficult problems. The fact that they cost both dollars and narrowing of individual liberty as you expanded governmental power, were not issues until both Mrs. Thatcher and the President raised them and raised them very effectively.

She was an extremely eloquent speaker and very persuasive. There had not been any major distinction, really between the previous conservative governments and the labor governments. It was very hard to tell who was in. They got into a tremendously difficult labor situation, in which most of the services were shut down, and she appealed to enough people who wanted to change that so that she was able to make a major difference there. She always worked very closely with President Reagan and supported him, admired him, and together they made really major changes in the whole political agenda and the whole political debate.

Riley

You mentioned the Strategic Defensive Initiative a minute ago. That’s something that historians look back on and try to find the roots of in Ronald Reagan’s thinking—

Weinberger

I think it was basically quite simple. The idea that you didn’t have any defense at all against these most lethal of all weapons continually troubled him. Churchill had a passage years ago—when he first became First Lord of the Admiralty. He went down to Spithead, which was where the big Naval maneuver area was, and he watched the British fleet maneuvering. He said,

It was very hard for me to realize that the whole fate of western civilization rested on these small ships, and if they were destroyed, you could lose the whole of western civilization overnight.

And President Reagan said two or three times, you have to remember that the Soviet Union is the only country in the world that can destroy the United States in an afternoon.The idea that you were resting your defense, not on even anything as fragile as these ships, but on nothing but a philosophic assumption—the philosophic assumption that everybody would behave the way we would, and that you would not have a nuclear war because it would be too horrible, and everybody would understand that. So if you had no defense against it, neither side would attack. It was a convoluted theory, but it was the mutual assured destruction theory, and it had been accepted as complete gospel. When you challenged that, you were absolutely repealing the education of almost everybody who was an expert in these fields. So it was a completely revolutionary doctrine, but it was a very logical doctrine.

Very few people really understood until the debate got under way that we had no defense whatever against these missiles, and that we were totally and completely at their mercy. They had started violating the ABM [Anti-Ballistic Missile] treaty—which was the one that forbade the defenses, enacted the mutual assured destruction theory into treaty form—within weeks and the Soviets were working continuously to get this kind of a defense, whereas we were not. We had dismantled the one system that we had and all the rest.

Later on, I had a lot of arguments with some of the British defense people on the ground that they had no evidence that the Soviets were violating the treaty, whereas we knew that they had these huge radars across Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Siberia, Krasnoyarsk, and other places, whose sole purpose was to detect incoming missiles. All this was forbidden under the treaty. It wasn’t until almost the end of the cold war—right after the end of the cold war—that the Soviets admitted that yes, they had violated the treaty. They had started working on defense immediately in 1979 after signing. They were convinced, many of them, that we could get a strategic defense and they had not been able to get it, and this would not only put at risk, but render impotent, their huge missile arsenal if we got it. So it was clearly a factor in their ultimate willingness to give up.

Knott

Could we get you talk a little bit about specific instances where American forces were used? Perhaps, starting off, you mentioned earlier the Weinberger Doctrine, and you wanted to take issue with one of the topics we had in our book here that used the phrase

your reluctance to involve American troops in missions . . .

Weinberger

Yes. Saying the Weinberger Doctrine was my

reluctance.

Well, it wasn’t reluctance to involve American troops. It was, first of all, a recognition of my responsibility for the care and safety of the troops, which is a heavy responsibility and a lot different from people in other departments—like the State Department—who had basically the idea that if you put a battalion here, a regiment there, or something, it would make a major difference.The doctrine grew out of the Vietnam experience. I’d been out of office all that time, was not in the Army or anything, but the Vietnam war was the first war we ever went into that we did not intend to win. I basically took the idea—with my basic unhappiness with that—and put the idea together that yes, we should use American troops when it was a matter of supreme national interest. And when it was, then we should not only use them, but we should use them with a clearly stated objective that we could achieve, and stay there and support them until we had achieved it, and then leave. But we shouldn’t go in piecemeal, and we shouldn’t do what we did in Vietnam, which was to feed twenty thousand, thirty thousand, a hundred thousand—each number was supposed to be enough to contain the north. We never wanted to defeat the north. This was a terrible thing to do, to ask people—our troops—to commit their lives to a cause that we didn’t consider important enough to win.

So that was the basic roots of the doctrine. In fact, I told the President, in discussing these things before, that I would not be able to stay on as Secretary if there was ever any desire to put a few American troops here and a few more there and not win. He agreed. If it was important enough to commit people and ask them to commit their lives, then we had to be determined enough to win, to support them, to have the objective of supporting them, and stay there until we had won and then leave. That’s essentially what we did on a much, much, smaller scale in Grenada, and with Libya where, again, Gaddafi challenged us not to ever enter the Gulf of Sidra, which he said were territorial waters of his. We said,

No, they’re open waters.

Freedom of navigation has been one of our tenets since the American Revolution, and we would go where we felt it was necessary to go to exercise the fleet. He made some feeble attempts to attack that, and they were immediately destroyed.Knott

Could you comment on the Marines in Beirut and that operation?

Weinberger

Well, that’s one of my saddest memories. I was not persuasive enough to persuade the President that the Marines were there on an impossible mission. They were very lightly armed. They were not permitted to take the high ground in front of them or the flanks on either side. They had no mission except to sit at the airport, which is just like sitting in a bull’s eye. Theoretically, their presence was supposed to support the idea of disengagement and ultimate peace. I said,

They’re in a position of extraordinary danger. They have no mission. They have no capability of carrying out a mission, and they’re terribly vulnerable.

It didn’t take any gift of prophecy or anything to see how vulnerable they were.When that horrible tragedy came, why, as I say, I took it very personally and still feel responsible in not having been persuasive enough to overcome the arguments that

Marines don’t cut and run,

andWe can’t leave because we’re there,

and all of that. I begged the President at least to pull them back and put them back on their transports as a more defensible position. That ultimately, of course, was done after the tragedy.Knott

Can you tell us anything about the impact that the tragedy had on President Reagan?

Weinberger

Well, it was very, very marked, there was no question about it. And it couldn’t have come at a worse time. We were planning that very weekend for the actions in Grenada to overcome the anarchy that was down there and the potential seizure of American students, and all the memories of the Iranian hostages. We had planned that for Monday morning, and this terrible event occurred on Saturday night. Yes, it had a very deep effect. We talked a few minutes ago about the strategic defense. One of the other things that had a tremendous effect on him was the necessity of playing these war games and rehearsing, in which we went over the role of the President. The standard scenario was that

the Soviets had launched a missile. You have eighteen minutes, Mr. President. What are we going to do?

He said,

Almost any target we attack will have huge collateral damage.

Collateral damage is the polite way of phrasing the number of innocent women and children who are killed because you’re engaging in a war, and it was up in the hundreds of thousands. That is one of the things, I think, that convinced him that we not only had to have a strategic defense, but we should offer to share it. That was another of the things that was quite unusual about our acquiring strategic defense, and which now seems largely forgotten. When we got it, we said he would share it with the world, so as to render all of these weapons useless. He insisted on that kind of proposal. And as it turned out, with this cold war ending and all, it didn’t become necessary.One thing that disappointed him most was the reaction of the academic and the so-called defense expert community to this proposal. They were horrified. They threw up their hands. It was worse than talking about evil empire. Here you were undermining the years and years of academic discipline that you shouldn’t have any defense. He said he simply did not want to trust the future of the world to philosophic assumptions. And all the evidence was that the Soviets were preparing for a nuclear war. They had these huge underground cities and underground communications. They were setting up environments in which they could live for a long time and keep their command and control communications capabilities. But people didn’t want to believe that and therefore didn’t believe it.

Knott

Could you talk a little bit more about the Grenada operation?

Weinberger

Yes. Grenada was, again, on a much smaller scale. First of all, the neighbors. Mrs. [Mary Eugenia] Charles, who was the Prime Minister of one of the neighboring Caribbean countries, came to Washington to urge us to do something about it. This construction was going on in Grenada, and the government there was in complete anarchy. The American medical students were going to be an obvious target. But then the rest of the outer Caribbean nations, bigger than the one she represented—she was Dominica, I think—also said we needed to do something to prevent the construction of this airport and to restore some kind of a government in Grenada that would protect the rights of people. We agreed to do that.

Again, we first of all had the plans that came to me, and I—having in mind the problems with the Iranian hostages, the attempts to rescue them—basically almost automatically doubled whatever the Joint Chiefs felt was a required force. So we went in with a very, very large force, which was criticized later on the grounds that it was much too big. But what we did was to overcome all resistance and free the students, get them out. Their Dean—who was safely in Brooklyn, New York—said they were never in any danger. But the students felt they were. They came to the White House later and thanked the President in a very moving ceremony.

We did that. But we also then helped install a framework for a government that the people would chose, and we left. Did it all within a month, I guess, little less than a month, and the government structure they chose is still there. Democratic procedures were restored, and the students got to come and go as they wished, and the airfield no longer was a threat.

He was also very concerned that Cuba had been allowed to go too far and had become a threat. Grenada was a decisive action—a small one, but very successful in the sense that it accomplished what we wanted. There was a lot of criticism of it: We didn’t have enough maps, and we didn’t have this and that, and we didn’t have very good communications between the various units. But it was very hastily put together, and we won. So it would be hard to say, from my point of view, that it was not successful.

Riley

Was there discussion internally within the administration about trying to do something more dramatic about Cuba?

Weinberger

Oh, at the beginning, yes. But I think the Bay of Pigs was a continual reminder that it would have to be something that was effective. And there wasn’t any immediate direct provocation. It was one of the things that I put in the six points there. You had to have some reasonable anticipation of support of the American people and the Congress. You couldn’t fight a war against an enemy here and against the American people at home. That had been because of the build-up of steady opposition to the Vietnam war. A lot of people misinterpreted that as you had to take a Gallup Poll before you went anywhere, which clearly was not what the criteria said.

Knott

Were you supportive of the President’s effort to arm the Contras and to overthrow the—

Weinberger

No. There was no presidential plan to do that because the congressional votes had come in against it. I was strongly opposed to the idea of giving arms to the Iranians, or to anybody over there, because we’d spent a lot of time and expended a huge amount of effort to persuade other countries not to sell them anything. The proposal was that we’d sell them arms ourselves in return for their helping to get our hostages back. It was said,

We have to deal with these moderate elements in Iran.

I said,There aren’t any moderate elements. All the moderates were killed long ago, and what you’re dealing with are a bunch of unreliable and thoroughly dishonest and corrupt arms dealers.

But the President’s idea of trying to get the hostages back overweighed almost everything—including, as he said later, all his own lifetime teachings and doctrines. But he was so unhappy about the idea of Americans being held against their will and our being unable to pull them out that he was willing to try even this, which, he said later, was a great mistake. He said, [George] Shultz and Weinberger were right, and I was wrong. Which was a generous, but a correct way to phrase it.

Knott

There were stories at the time that the President was deeply moved when he would meet with the families of the hostages. Was that a key factor in his—

Weinberger

Absolutely. Those meetings destroyed him, absolutely. These families of the people who were being held and the families of the people who had been killed in an airplane accident coming back from doing duty in the Sinai. All these things were very, very hard on him. He brought a great deal of comfort to them, but the idea of allowing Americans to be held—as the Iranians did earlier—by these terrorist groups in Syria and whatever bothered him very much.

Riley

One of the things that come out of a reading of the briefing book is that you had what might be characterized as a very complex relationship with George Shultz.

Weinberger

Well, yes. I think that’s overemphasized. There are certain institutional differences between the two Departments. Oddly enough, I was generally on the side of more caution and more concern about the safety of the troops. I also was very skeptical about the effectiveness of putting in a few regiments or a few battalions or joining international forces, particularly in the Mideast, where they would go in without any kind of proper rules of engagement and where they would be basically unable to do anything to protect themselves. So we had disputes there. We didn’t have any disagreement at all on the Iran hostages.. We both regarded the [Robert] McFarlane proposal as perfectly absurd and dangerous, and said so many times. I believed we’d convinced the President in two meetings, but in the third meeting on it, it became quite apparent that we had not.

He decided to go ahead with it and allow the Israelis to send some of the arms we’d given to Israel to Iran and to see if it was possible to get some hostages home. I don’t think we ever did. One or two were released within the time frame, but I didn’t think it was for any reason other than to continue the idea of getting these arms over to them. The idea of them selling them at much higher prices than they were supposed to have been charged anyway, and using the balance to finance operations that the Congress had opposed and had turned down in Nicaragua, was completely illegal, as far as I was concerned. I said so many times.

Riley

Did you have institutional concerns at the time about what was going on on the President’s National Security Council staff? We routinely read—and this is across Presidents—that with the Departments—the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense—being positioned outside the White House, there is often institutional tension with the President’s National Security Advisor.

Weinberger

Well, it would depend who it was. We didn’t have any tension at all with Bill Clark. McFarlane had a lot of adventures that he wanted to get into, and basically from my point of view was always trying to develop something like the trip to China that would be a huge breakthrough. He had a lot of wild ideas like trying to put some divisions down into Egypt to go after Libya—things like that that just seemed not only particularly silly, but very risky, very dangerous, and very unproductive. That was on individual items, but on the big item—the hostages being held by the Iranians—Shultz and I were in total agreement right straight through.

Knott

Would you be willing to comment on William Casey? Any reflections on CIA Director Casey?

Weinberger

Bill Casey was, again, a very underestimated sort of person. Bill Casey was quite a scholar. He had a huge library. He wrote some essays about the American Revolution. He was very interested in expanding the capabilities of our intelligence service, not only to get information, but to carry out covert operations. He was influential with the President. He was one of the few people who had helped with the presidential campaign the first time, when nobody else would pay much attention to him. The President liked him. He was a very, basically, secretive sort of person, which went with his job. He was far more capable than most people were willing to acknowledge at the time.

Knott

Were you comfortable with the notion of covert warfare?

Weinberger

Well, if you had the means to do it, and if you were going to accomplish something, the fact that it was covert was not a problem with me. I understood the people’s right to know, but I also understood that there was no enemy’s right to know. A lot of these things—to safeguard the troops participating—had to be carried out in a clandestine way.

Riley

Thus your decision in Grenada to keep the press out?

Weinberger

No, it wasn’t to keep the press out. It was a matter of very, very limited logistics. We had to stage Grenada from a neighboring island, with the inability to take very many planes off or on at any one time—not nearly enough to put a division in. So in the initial landings—the initial parachute drops and all—there wasn’t really any room for anybody else.

The press went in on the second day, I think, or maybe the third day—I think the second day. They didn’t actually come in the landing, and there was a lot of grumbling about that. But we had nothing to hide. We just didn’t have room, frankly. There were higher priorities.

Knott

Could you tell us why Secretary of State [Alexander] Haig didn’t work out, or am I jumping to conclusions there?

Weinberger

Well, he had kind of a strong personality. He’d been in positions where he’d been in charge. Someone said it was a great mistake to give anybody a position with the title of

supreme

in it. He was the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, and he was a very good soldier and a good general. But from the beginning he was obsessed with the idea that people were trying to undermine him. He was very worried about perquisites and his own primacy as foreign policy advisor. He disliked intensely anybody else commenting on any foreign policy matters in the presence of the President—little things like that that sort of build up after a while. He kept getting angrier and angrier. He threatened to resign several times. Finally the President said,All right.

That’s the danger with a resignation threat. Sometimes the President gets to believe it and accept it.Haig was a very brilliant man, very able man. I was always more amused than anything else by his violent reactions for any opposition being raised to things that he wanted to do. But he wanted to be President, which was fair enough. I think he just felt he was being undermined by a cabal of the White House. He had not been part of the Reagan team in Sacramento, obviously. He had had quite an independent remarkable career, and was sometimes a bit difficult.

Riley

Looking back at the Reagan years, historians devote a fair amount of attention to the different organizational structures in the White House and how that worked over time. I wonder if you could tell us what your working relationship was with each of the members of the troika during the first term, and then whether your working relationship with the President and the White House changed with the advent of a stronger Chief of Staff under Don Regan.

Weinberger

I don’t think materially, no. I had the good fortune to have worked with the Governor before, and a lot of those fights in Washington were about access and whether you could see the President, who was the gatekeeper, who controlled the paper going into the President and all that. I didn’t really pay an awful lot of attention to that, because if I needed to see him, I knew I could. But I didn’t need to go over every week to demonstrate that I could see him. I didn’t try to use that relationship that I’d had with him, except on budgetary matters or things where his decision was clearly required—whether we should proceed with one or two bombers, whether we should to continue to try to develop the B-2, what we should do about the B-1, what level of budgetary support was required.

Those would be generally argued out in the Cabinet room, and he was very supportive. Don Regan was Chief of Staff for the second part of that term, and [James] Baker and Deaver and Ed Meese had been a sort of group of three who divided the Chief of Staff’s responsibilities. Baker was a very ambitious fellow and worked very closely with Deaver. Ed Meese was more or less being excluded, and you had a lot of internal discussions and wrangling back and forth. But eventually when Don Regan was appointed and Baker went to Treasury, Don was very, very clear that he was in charge. As far as I was concerned, that didn’t really make any particular difference.

Riley

We’ve heard from others that the accessibility to the President became a bit more difficult during the second term because Regan considered himself a—

Weinberger

That may very well have been. I didn’t notice any particular change, because I had access although I didn’t use it very often. There were certainly a lot of stories to that effect. Again, the real problem here is to sort out the truth from the accepted wisdom, as happened in the convention—with that big so-called dream ticket that I mentioned. The press understood that was all settled, and their only question was

Why did it come unstuck?

It had never been stuck. It had never been glued together.Riley

Well, this is why we’re having this conversation.

Weinberger

Certainly.

Knott

Can I ask you about another event, and that is the Falklands War? I attended a conference not too long ago in London, marking the twentieth anniversary of the war. A number of the British Cabinet officers who were there spoke very fondly of you, saw you as a pivotal figure in terms of providing assistance to the British.

Weinberger

We did provide assistance. To my mind it was a very, very clear and simple case. Here was our oldest and strongest ally and a member of NATO, and our NATO obligations were to come to the defense of any one of the NATO members who was attacked. Britain had been attacked. The idea that this was just a small sheep-station was totally irrelevant as far as I was concerned. It was part of the British Empire, and sovereignty was in Britain. You had a corrupt military dictatorship from Argentina on one side. You had our oldest and strongest ally and a member of NATO on the other side. I didn’t see what the problem was, so to speak, except that we should support Britain as completely as possible.

There were a lot of attempts at settling it diplomatically. Settling it diplomatically would have meant something to the effect that Britain could keep the Falklands for two years, and then they would revert to Argentinean control, and we wouldn’t have a war, and everybody would be happy. That was totally foreign to what I thought should happen and what Mrs. Thatcher thought should happen. They obviously needed a lot of help. Here they were trying to retake islands that had already been captured, seven thousand miles away, with only one basic stopping place in between that they owned. We had obtained from them—in order to help—the lease rights to store things on Ascension Island, and we helped them in every way we could.

While Al was going back and forth on these shuttle flights, trying to set up a diplomatic solution, Britain was moving ahead with their attempt to retake the island. Mrs. Thatcher was told by her military, and I was told by our military, that it was not possible—that the idea of trying to mount an invasion force that far away with the depleted peacetime forces that they had couldn’t be done. Mrs. Thatcher said,

The possibility of defeat does not exist.

Because she said that and because she meant it, and we helped, it didn’t exist. Ultimately they did retake them. We certainly helped, but they did the work.

Knott

There was some dissension within the Reagan administration, led by Mrs. [Jeane] Kirkpatrick, as I understand. Is that accurate?

Weinberger

There were a lot of people who thought that we would ruin our relationships with Latin America, and that we would violate the Monroe Doctrine, and all kinds of things like that. But I said to them,

We have no interest whatever in supporting a corrupt military dictatorship that has invaded this island without any provocation whatever, and if we give substance to it and support it, we will encourage this kind of aggression all over the world. And we will cast aside our NATO obligations—to say nothing of the basic relationship that we have had with Great Britain for longer than anybody can remember.

So we had to go in and do everything that we could to help them, and we did.My role, primarily, was that of an advance quartermaster. I said that any of their requests for arms or aid or anything was to come directly to my desk and not go through the, literally, 31 in-baskets that these requests normally pass through. I said it was to have a note on it as to when we had agreed to their requests, and if not, why not. This did have a stimulative effect on getting the aid out very quickly. Oh, some things—such as wire netting that they used to hold down the sand to make a temporary air strip, and things of that kind—were very vital. That particular request was delivered to them the next day.

Ascension Island. They had to go all the way down there, and we placed a lot on Ascension down there, to give them staging for some of their equipment. We helped a great deal, but they did it. They were kind enough to say that our help was substantial—which it was—but they retook the island.

Knott

There was some suggestion at this conference I attended that you were ahead of President Reagan on this, that it took him a while—

Weinberger

A couple of weeks. There hadn’t been a formal decision made, and Haig was still doing the diplomacy back and forth. But I knew that the President ultimately would be supportive of that as opposed to supporting this corrupt Argentinean military dictatorship, which has changed in the subsequent years. Everybody is very friendly now.

Knott

Another very controversial event during the first term was the sale of the AWACs [Airborne Warning and Control System] planes to Saudi Arabia. Could you comment on that episode?

Weinberger

Well, that was, again, something that we thought would improve our own security. It would give a lot longer eye, so to speak, to us and the Saudis—where the planes would be based—of any potential invasion, or any attempt to retake the oil fields. That was part of the old Soviet—before that, the Russian—doctrine, that the path through the oil fields was down through Afghanistan, and it was important we have as much foreknowledge of that as possible. So the AWACs were mostly—the Saudis would own them, and they were based in Saudi Arabia, and we were able to use them and get information from them. The AWACs simply extended your vision hundreds of miles out. They never had any offensive use. They were entirely reconnaissance and intelligence-gathering.

Riley

Were you involved at all in the congressional relations effort to get that through Congress?

Weinberger

Oh sure. Yes.

Riley

Can you tell us a little bit about it?

Weinberger

Just that there was a lot of opposition to it because the Israelis basically were worried about the Saudis—or anybody else—having that capability. We had to spend a fair amount of time demonstrating that it wasn’t to enhance any Saudi capability. It was to enhance our own capability to get intelligence gathered as far ahead as possible. The fact that they would be based in Saudi Arabia, or even that they would be owned by the Saudi government, would not enhance or increase any potential danger to Israel. But the Israeli supporters in Congress were obviously very strong and were very worried that there was continual Israeli opposition to this idea. So we had to use persuasion that it was something that would enhance our own security.

Riley

Who were your closest allies on Capitol Hill?

Weinberger

Oh, we had a number. We had a number of members of the Armed Services Committee. It was a shifting set of coalitions. On some things people were very supportive. Some of the Democrats on the Armed Services Committees were very helpful. Some of the Republicans were very helpful. Many were opposed. Many were worried that too much was being spent on defense and that other domestic priorities were being neglected. They adopted basically the Stockman views. It was always a struggle, and it was understood to be, because of the basic opposition that democracies have to spending money on defense. That’s a very old historical thing, with which I was very familiar, but one had to work more or less constantly to try to overcome.

Riley

Could I ask you who your most formidable opposition was on the Hill? Do you recall?

Weinberger

Oh, practically everybody. There was a lot. First of all, the Democrats, of course, from a partisan point of view, who were anxious to undercut the enormous popularity of President Reagan, and so anything that he would propose automatically had built in opposition. And you had some Republican opposition, people who had been there for a long time and who had been accustomed to the idea of trying to promote détente and not do anything provocative, and not do anything that required big increases and so on. As I said, it was something you could do for three or four years, but not beyond that, because the domestic pressures and the partisan pressures combined were such that it became very difficult to accomplish anything.

Howard Baker was the Republican leader for a while at that time, enormously helpful—personally somewhat skeptical, but perfectly willing to support the President and help. There were a number of others. But many of the people who were supposed to be very strong supporters of big defense—Senator [Sam] Nunn, for example—were not, because the President was proposing them, and they were on the other side. You had a lot of differing forces. You had to put together shifting coalitions from time to time to get a majority. The President was enormously helpful because he had huge popularity, and that was a very big asset.

Knott

I’m sorry to keep jumping around here, but I was wondering if we could go back to the Middle East. You had a reputation at the time, at least in some quarters, of being an Arabist.

Weinberger

I know that, and that was not right, really. My big point was, constantly, that we needed more than one friend in the Middle East. The thing we could do that would help Israel the most was not to give them money and not arms, but to give them friendly neighbors. And the only way you could ever get that was by demonstrating the fact that we wanted to have strong, friendly relationships with a number of Mideast countries. I had hoped, when the Gulf War was fought, that that would, once and for all, lay to rest this idea that all we ever cared about was one country. The Gulf War proved that we were perfectly willing to use our arms and our treasury to try to prevent hostile, aggressive conduct by a number of other countries—Iraq at that time. That would demonstrate—to Israel and many other countries—that we were not simply interested in having a single alliance.

So that was basically the burden of my efforts, and in the course of doing that—because that sometimes involved actions that strong Israeli supporters felt weren’t sufficiently supportive—this idea developed that I was basically more for the Arabs than not. What I was trying to do was to give Israel friendlier neighbors. I never wanted to undermine the Israeli-American alliance at all, but I did want very much to have a situation in which they themselves would be able to live in peace and friendship with a number of other countries.

We made a lot of progress with Jordan, a lot of progress with Egypt at first. But it was difficult because many of the people—even in Saudi Arabia—were strongly against Israel for historic reasons. This was a thousand-year-old dispute, and it was something that evoked enormously strong emotions and still does. But in trying to even the balance or whatever, without weakening our ties to Israel, the general impression of some of the Israeli supporters was that I was not sufficiently supportive.

Knott

I believe you were critical of the Israeli attack on the Iraqi nuclear reactor.

Weinberger

Yes, yes.

Knott

Any second thoughts about that?

Weinberger

That was a bolt from the blue, and obviously I was afraid we were going to unite a great many of the Moslem countries, even more so than they were then. It turned out it didn’t have as many of the damaging side effects as I feared. It was an extraordinarily skillful job. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the photographs. The Osiraq reactor was enclosed by a huge fence, without any particular effort at camouflage or anything. It was right out there in the desert with this enormous fence all the way around it. When the Israelis had finished bombing, the fence was still there, but nothing else was there. It was an extraordinarily skillful, effective job. It did anger a lot of people, but it also impressed upon them that this was a country that, although it had extraordinarily narrow borders and was in an extraordinarily vulnerable position, was not a country to be taken lightly.

Knott

Another question dealing with Iraq. Late in your tenure, there was an effort to reflag the Kuwaiti tankers and put them under American protection—

Weinberger

Which was done.

Knott

This was something you were supportive of?

Weinberger

Oh yes, very much so. This was, again, freedom of navigation. This was an attempt to close the Straits of Hormuz and the Gulf, through which a very large amount of commerce and oil pass, and we were very supportive of that commerce. We knew that if the Kuwaiti tankers and the others were not going to get protection from us, they would go to the Soviets, who were very anxious to insert themselves in every way into Mideast matters.

Knott

To what extent was terrorism on your agenda?

Weinberger