A view from the George H. W. Bush White House

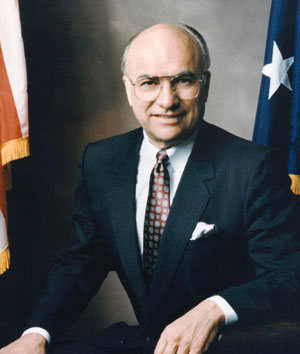

The memories of Clayton Yeutter, President Bush's secretary of agriculture, who passed away recently

This month, George H.W. Bush’s Secretary of Agriculture Clayton Yeutter passed away at his Maryland home from colon cancer. He had different roles in Bush’s presidency: secretary of agriculture, Republican National Committee (RNC) chair, and counsel to the president, all captured in his 2001 interview for the George H.W. Bush Oral History Project.

Spotted owl controversy

The agriculture department played a role in trying to save the spotted owl, a near threatened species. This illustrates the challenges executive agencies face when it works with environmental groups, and for Republicans, it was frustrating. It is a battle that the Trump administration will have to face right now. The spotted owl was an even trickier situation, because conservation research on the owl couldn’t provide a path toward resolution.

It’s an example of an intractable issue that is extremely difficult to handle because many of the advocacy groups are never going to be satisfied.

Yeutter: Spotted owl was a huge controversy that we really struggled a lot with. It’s one of those problems that is almost impossible to solve. It was one of the earlier reflections of the rise of environmental advocacy groups as an important factor in political decision-making. They zeroed in on the spotted owl, not because they had great concern for the owl but because they wanted to do what they could to halt the harvesting of trees on national forest lands and national parks as well. So it was really a tree-planting controversy rather than a spotted owl controversy, but the Endangered Species Act provided the basis for building those arguments.

The controversy involved not only USDA, but the White House and the Interior Department. It was a controversy that was still swirling when I went to the White House to coordinate all domestic policy issues in ’92. And for that matter it’s not yet resolved today. It’s an example of an intractable issue that is extremely difficult to handle because many of the advocacy groups are never going to be satisfied.

***

We were trying to work out X million board feet of cut, but every time we would almost reach agreement on a number, the environmental groups would want a little bit more, so the number would keep moving a bit. We could never get to a final conclusion. And every time we were about to agree on the acreage, that number would get a little bit bigger too. It was a sliding scale in terms of what the ultimate objective would be. We probably could have handled the issue better than we did, but to this day, I don’t know what we should have done differently.

Q: Did the White House get involved before you went over?

He thought they should have just thrown them all out of their offices and gone back to work.

Yeutter: Yes, Sununu was involved early on. Coming out of New Hampshire, which has a lot of forestry, he had a personal interest in such issues and he didn’t like the environmental groups, of course. So he was determined to try to get this issue behind the administration, and if possible he really wanted to give the back of his hand to the environmental groups. But because of all the lawsuits, that just wasn’t possible. He also was frustrated with the folks at Interior and at Agriculture at the working level, meaning the Forest Service and the Parks Service, because Sununu felt they were all bending over too far to accommodate the environmental activists. He thought they should have just thrown them all out of their offices and gone back to work.

On two or three occasions, he called me and said, “You’ve got to fire Dale Robertson,” who was the chief of the Forest Service. “We’ve got to get somebody in there who will be a lot tougher with those environmental activists.” I, of course, refused to fire him because I felt Robertson was doing an excellent job. He was trying hard to balance all these conflicting interests. So, I protected Dale. Knowing John Sununu’s personality, and he’s a great friend, after about 24 hours he’d settle down, and I really didn’t believe he wanted Robertson fired.

Alar apple scare

Alar was a chemical used to regulate apple growth and keep them on the trees as the fruit ripened. The EPA ran studies about its carcinogenic level, but it was still on the market. In February 1989, the show, 60 Minutes, ran a segment about the problem of Alar, and the EPA decided to ban it. Grocers were pulling apples from the stores.

Yeutter: Another issue that was quite interesting was the controversy over the use of Alar on apples. That was and is an excellent illustration of how wrong the media can be, and how much damage they can do when they’re wrong and never apologize or even acknowledge error. This was a case, as you’ll recall, where the allegation was that these apples were unfit for human consumption, that a serious health risk was involved, in the use of the particular pesticide Alar. The U.S. apple industry was devastated by these charges. Apple sales in U.S. supermarkets went almost to zero. The story had a huge adverse impact.

Dr. James Anderson: Well, for a little time, apples almost disappeared from the grocery stores.

Yeutter: They did. People would not buy them, and as I recall, the allegation was that this was a particular danger to children…but they were having trouble finding an alternative that was as effective, so there was a controversy as to whether they should continue using it, and how they would deal with problems at the producer level without it. We were then having meetings with FDA and EPA seeking to coordinate the administration’s response to this, while trying to reassure people that there really wasn’t a significant health risk. There was good cooperation among the governmental agencies. Fundamentally EPA, FDA, and USDA all had the same message, and it was a message of reassurance. But once that kind of story hits, it’s extremely difficult to reassure people. People are not prepared to trust government agencies very far under those circumstances. As it turned out, there was no health risk at all; the allegations were totally false. The original story should never have been launched by the media. It got worse as time went on, and everyone now agrees that there was zero scientific evidence of any cause for concern. But it’s a good case of alleged concerns running amok through the media, frightening consumers, while nearly destroying apple producers who had done nothing wrong.

RNC chair

From January 1991 until February 1992, Yeutter was chairman of the Republican National Committee. The 1992 presidential election came down to the economy, and Bush faced primary challenger, Pat Buchanan, and then Bill Clinton and Ross Perot.

Yeutter: Then the negatives picked up some more because of the Buchanan candidacy and then later the Perot candidacy. That brings back the question of the timing of an administration response to all these challenges. I did a memo to President Bush clear back in July 1991, saying, When you go to Kennebunkport in August it’s time to get your ’92 team together. We’ve been getting a lot of negative commentary, so it is time to get organized, to handle things internally within the Republican Party (especially because of the conservative disaffection), and also time to handle things externally.

His response in one of those little side notes was: No, it’s too early. In my judgment, that was a mistake. It was the failure to tool up in the fall of ’91 that led to the Buchanan candidacy in early ’92. Had the Bush administration had its campaign team organized and in place and ready to hit anybody who might come along on the Republican side, they might have headed off a Buchanan challenge. Pat might have said, If I get into this, these folks are going to swat me. But that didn’t happen, and when he went in, there was nobody there to swat him. He had the field to his own for a while.

***

So, you really had only the White House apparatus being able to respond to the Buchanan candidacy, and that wasn’t a good situation. Buchanan was able to build his candidacy on the negatives of the time, the economy and criticism coming from conservatives because of the read my lips breach. Then, of course, the criticism began on the Democratic side as well. So the White House was being hit from the left and the right simultaneously. Not surprisingly, the media began to pick up on all of that and say, Whoa, wait a minute, Bush’s popularity has gone from 90 to whatever it was, and this is an administration that’s in trouble.

***

As we talked a bit this morning, there are always constraints on what the President of the United States can do on the economic side. Presidents always get more credit than they deserve when the economy is good, and more blame than they deserve when the economy is bad.

***

If you read the newspapers at that time and watched the evening news, you would have thought that thousands of people were being laid off every day

There was a feeling in ’92 that even though things were tough out there, they weren’t as tough as they appeared in the media. If you read the newspapers at that time and watched the evening news, you would have thought that thousands of people were being laid off every day, though that was not the case. There were certainly layoffs, and there certainly was a lot of trepidation, but much of it amounted to fears that were never converted to reality. It was fear of the unknown, and the unknown was not nearly as troublesome as people thought.

So we were dealing with a question of reality in some cases, perception in a lot of others. The question was, How does the White House get on top of that situation and project a President who knows and understands the economy, is sympathetic to those who are in trouble, and has a plan for the future that will bring us into recovery?