Lyndon B. Johnson: The American Franchise

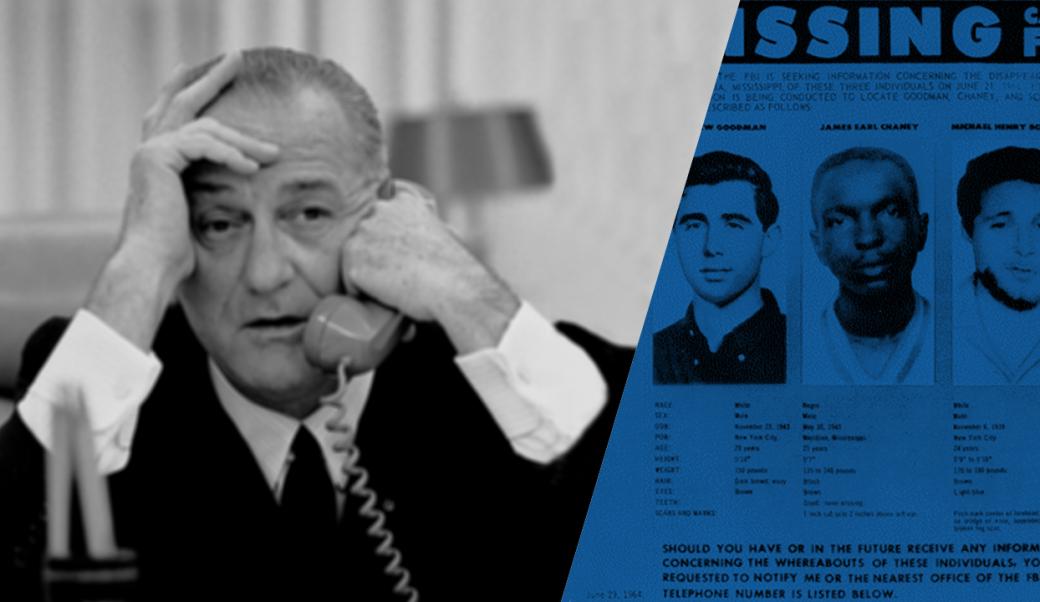

There is an eloquent irony in the fact that it took a southern President to enact civil rights legislation in America. Lyndon Johnson's triumphs in this critical area emboldened minorities to assert themselves more strongly in society, and he must be considered a major player in it. He also nominated the first African American, Thurgood Marshall, to the Supreme Court and the first African American to the cabinet. During his time, however, a key component of Franklin Roosevelt's coalition left the Democratic fold: white southerners. Many of them were unnerved by the changes wrought by the civil rights movement and began to change their party allegiance away from the Democratic Party.

The 1960s marked a new period of political mobilization and protest. Antiwar demonstrations and civil rights demonstrations in the streets and student demonstrations on campuses all attacked existing authority figures and the legitimacy of existing institutions. There were calls for reform of corporate practices, university governance, political party nominating procedures, and the seniority system in Congress—hardly any American institution escaped from the intense scrutiny of some activist group.

American society in the 1960s entered a period of "personal liberation" in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination. Women no longer accepted the role of "dutiful helper and housewife," and the women's liberation movement was born. Young people no longer accepted the dominant culture as a given, and a "youth culture" spawned by television advertising and a "counterculture" formed to oppose the commercialization of everyday life competed for the allegiance of young people.

During the Johnson years, the nation experienced "long hot summers" of racial and campus unrest. There were riots in Harlem, New York, in 1964 and in the Watts district of Los Angeles in 1965, both fueled by accusations of police brutality against minority residents. In Cleveland, Detroit, and Newark, in 1967, whole city districts went up in flames. In April 1968, Washington, D.C., erupted in the aftermath of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. "Burn, baby burn" became a slogan of the protesters. In many cities, National Guardsmen or federal troops had to restore control.

In his State of the Union Address of 1968, Johnson observed that "there is in the land a certain restlessness--a questioning." That was, perhaps, the understatement of his presidency.