Watergate: The president

Richard Nixon was a self-made man—until he unmade himself (Chapter 3)

“A man who forced himself to smile, when he loved to frown. A man who forced himself to shake hands, when his hands were already shaking.”

This was the description of President Richard Nixon in comedian David Frye’s 1971 parody album Richard Nixon Superstar. The joke gets at an essential dynamic in Nixon's life: Though often uncomfortable with others, he was driven to prove his worth in the brightest of spotlights. [Click the play button on the image to hear highlights.]

Frye's record also references other aspects of Nixon's personality: There was the seriousness, depicted as young Nixon runs for blackboard monitor. There was the secrecy, evidenced when Nixon won't reveal his secret plan to win the high school football game. There was the need to overcome a humble upbringing and prove his intelligence, as when Nixon remembers how all he got for Christmas was "an old I and a used Q."

Nixon was ripe for parody largely because, even with his vast reserves of self-discipline and a rough campaigning style, Americans could sense his vulnerability and all-too-human flaws. But no matter how much success he achieved, Nixon's need for approval was never fully met. He could not shake the sense that all he had worked for might be taken away, and that those who came from more privileged backgrounds looked down on him. This sense was so strong, it filled Nixon with hatred—a hatred with which, in his own words, he eventually “destroyed himself.”

A self-made man

Nixon's political rise was swift. Returning from World War II, he ran to unseat the popular five-term incumbent Jerry Voorhis as a representative from California's 12th district in 1946—and won. Four years later, he defeated former actress Helen Gahagan Douglas for a seat in the US Senate. Two years after that, Nixon found himself running for vice president on the Eisenhower ticket.

But Nixon's life had not been easy. His family was poor, and his father, Frank, had a notoriously short temper. A younger brother, Arthur, died at the age of 7, while Harold, three and a half years Richard's senior, passed away after a difficult battle with tuberculosis—a disease that took both him and the boys' mother, Hannah, away from the family.

Nixon was a standout student, but family finances prevented him from attending Harvard, and he stayed in his California hometown to graduate from Whittier College. Nixon then attended Duke Law School, but his scholastic achievements were not enough to get him into the FBI or one of several prestigious law firms to which he applied. A driving ambition evident throughout his life, however, left him looking for a way out of Whittier, and after a short stint in the Roosevelt administration's Office of Price Administration, Nixon joined the Navy.

Nixon the anticommunist

Nixon's win over Voorhis launched his political career. It also established the young congressman as an anticommunist crusader. Ironically, Voorhis boasted his own anticommunist bona fides, having refused money from any communist-influenced PAC. But that didn't stop Nixon from obfuscating the issue and implying that his opponent's loyalty was suspect. Once in Congress, Nixon took a leading role on the House Un-American Activities Committee, indefatigably pressing the investigation into the State Department's Alger Hiss. Nixon's aggressive pursuit yielded results when evidence surfaced that Hiss had indeed passed information to the Soviets, and he was convicted of perjury.

In his 1950 Senate campaign, Nixon painted his opponent, actress Helen Gahagan Douglas as a tool of communists, even printing a “pink sheet” that portrayed Douglas as part of a communist “axis.” The hard-fought campaign earned Nixon the nickname "Tricky Dick" and solidified his view of politics as a no-holds-barred street fight.

These three triumphs—over Voorhis, Hiss, and Douglas—were more than just political victories. Nixon had also vanquished three members of the “elite.” Hiss and Voorhis were from wealthy families and boasted Ivy League credentials. Douglas was not only a Hollywood actress herself, she was married to an even more famous leading man, Melvyn Douglas. Over time Nixon’s perspective would harden as he convinced himself that elites, Jews, and the press were his enemies, willing to conspire to destroy him.

Nixon, the everyman

Nixon had been a US Senator for only two years, and in Congress for only six, when clever maneuvering at the Republican National Convention helped lead to his selection as Dwight Eisenhower's vice presidential nominee. Then Nixon encountered his first political crisis: Rumors that a secret campaign fund was supporting a lavish lifestyle forced the candidate to defend himself in a nationally televised appearance to retain his spot on the ticket. Nixon's sterling performance as an “everyman” in what came to be known as the “Checkers” speech, after the name of the family dog, left him on the ticket and only a heartbeat away from the presidency for the next eight years.

Two victories, two defeats

Following an Eisenhower landslide, Nixon performed the duties of vice president admirably. He handled himself capably on foreign trips to South America, where Venezuelan protestors threw rocks at his motorcade, and the Soviet Union, where he stood toe to toe with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, defending American capitalism in what came to be known as the “kitchen debate.” When President Eisenhower suffered a heart attack, Nixon took charge, but with restraint, allaying fears of those in the administration who suspected he was an inveterate self-promoter. In 1956, the pair won a second term in another landslide.

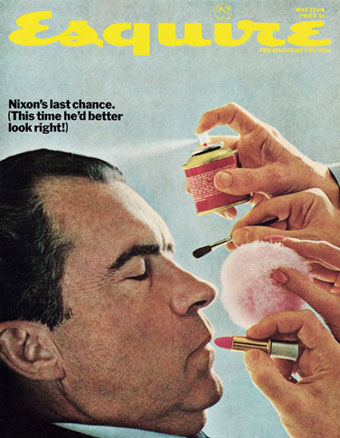

Nixon was the logical choice as Republican candidate for president in 1960 and found himself facing a former friend, and another elite opponent, in John F. Kennedy. His televised debates with Kennedy were another signature moment in his career—only this time, Nixon was to suffer. Recently ill, he appeared pale and sweaty compared to the “tan, rested, and ready” JFK. Nixon attributed his excruciatingly narrow defeat to the ruthless Kennedy machine, writing in his memoirs, “We were faced in 1960 by an organization that had equal dedication to ours and unlimited money, that was led by the most ruthless group of political operatives ever mobilized for a presidential campaign. Kennedy's organization approached campaign dirty tricks with a roguish relish and carried them off with an insouciance that captivated many politicians and overcame the critical faculties of many reporters.” He vowed to never let it happen again.

Attempting to bounce back with a 1962 run for California governor, Nixon lost again, and took out his frustration with the press in another memorable moment when he declared, “Just think how much you’re going to be missing, you don't have Nixon to kick around anymore.” Given Nixon's national stature, the margin of victory for incumbent Pat Brown was surprisingly wide.

Reaching the mountaintop

Typical Nixonian diligence, perseverance, and political savvy, driven by an ongoing need to prove himself, brought a “New Nixon” into the 1968 race for president. Portrayed as an older, wiser, and more statesmanlike version of the combative anticommunist, the candidate still lived up to his post-1960 vow to do whatever it took to win by allowing his campaign to interfere in Vietnam peace talks that could have given momentum to his opponent, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. A large Nixon lead shrank but didn't evaporate, and he finally took the oath of office as President of the United States in January 1969.

Standing at last at the apex of American politics, Nixon never felt entirely secure, especially with Congress in the hands of the Democrats. Eventually his staff began to contemplate ways to "screw" his political enemies using the powers of the executive branch. And the effects of his campaign's Vietnam interference, known as the “Chennault affair,” lingered. Conversations with Johnson during the campaign had alerted Nixon that the intelligence community had confirmation of the malfeasance, which may have contributed to Nixon’s focus on the Pentagon Papers leak and other materials related to Johnson's bombing halt.

Leaks also enraged the president, bringing together many of Nixon’s fears about elite enemies—men like Alger Hiss—secreted inside the government and plotting to bring him down, in league with the press. To combat the threat, the administration put together a top secret investigations unit inside the White House. The group, which came to be known as "the Plumbers," planned several break-ins—some of which it executed—to achieve its ends. It also included two men who would become household names once the Watergate scandal erupted: E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy.